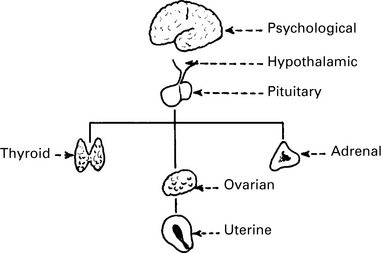

Chapter 6 Abnormalities of Menstruation

Physiological amenorrhoea

Menopause

The menopause is the cessation of menstruation (mean age 51 y) due to exhaustion of the supply of ovarian follicles. Oestrogen production therefore falls. This fall in oestrogen production is accompanied by a rise in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, which continues for a considerable time. In a proportion of women, menstruation ceases abruptly, but in many, the menstrual cycles alter. Frequently, they become shorter initially, but later they lengthen and tend to be irregular, before ceasing entirely. This phase is known as the menopause transition, and the final period is recognised only in retrospect, after 1 year of amenorrhoea. See Chapter 18.

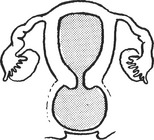

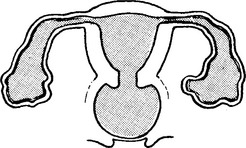

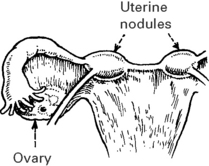

Uterine and lower genital tract disorders

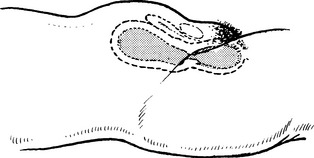

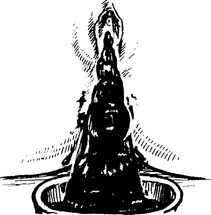

Imperforate hymen or transverse vaginal septum

Examination

A pelvic mass is palpated and may even be visible. The vaginal membrane or hymen is bulging.

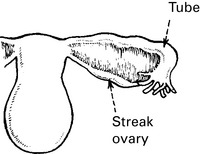

Ovarian disorders

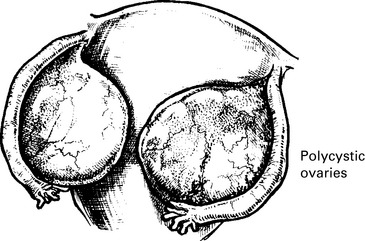

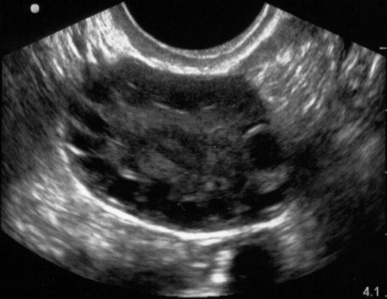

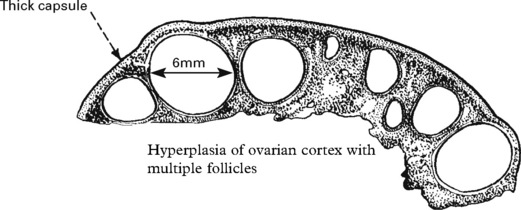

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

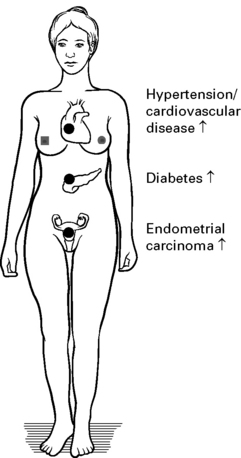

Long-term Effects of PCOS

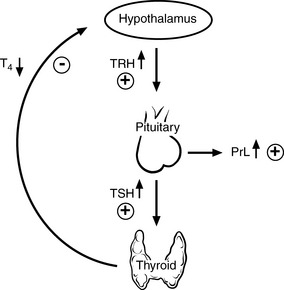

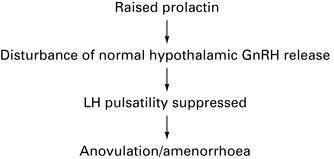

Pituitary disorders

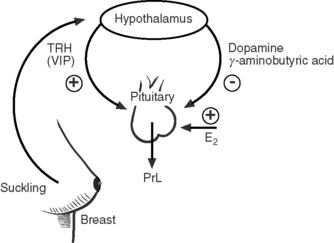

Hyperprolactinaemia

Aetiology