Termination of a pregnancy by inducing labour may be indicated because of a suspected or confirmed risk to the mother or baby, or both.

METHODS OF INDUCTION

The Bishop score

0

1

2

3

Dilatation (cm)

<2

2–4

>4

Length (cm)

>2

1–2

<1

Consistency

Firm

Average

Soft

Position

Post.

Mid Anterior

Level

0–3

0–2

0–1:0

0+

Total

(a). RIPENING THE CERVIX

(b). AMNIOTOMY (Artificial Rupture of Membranes)

Complications of Amniotomy

Placental separation (Abruption)

Bleeding

Prolapse of the cord

Pulmonary embolism of amniotic fluid

(c). INTRAVENOUS OXYTOCIN

Effect on uterine activity

Complications of oxytocin

Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns

Hyperstimulation

Rupture of the uterus

Water intoxication

ACCELERATION OF LABOUR

FAILURE TO PROGRESS IN LABOUR

CAUSES OF FAILURE TO PROGRESS IN LABOUR

Dysfunctional Labour

Malposition/Malpresentation

MALPOSITION/MALPRESENTATION

Dangers

DIAGNOSIS OF MALPRESENTATION

2. VAGINAL EXAMINATION

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Abnormal Labour

Such indications are:

Hypertensive disorders.

Prolonged pregnancy.

Compromised fetus, e.g. growth restriction.

Maternal diabetes.

Rhesus sensitisation.

Hypertensive disease and prolonged pregnancy have long been the largest groups. Induction in such cases has often been carried out on epidemiological data as opposed to established risk in an individual case. Modern methods of fetal assessment aim to establish the risk in an individual and thus avoid needless intervention.

Other indications for induction are:

Fetal abnormality or death — the main reason for intervention is to alleviate distress in the mother.

Social — induction may be requested by a mother for a variety of social or domestic reasons. The obstetrician may reasonably agree to such requests if the findings are favourable for delivery and if there are no features which would make intervention unusually hazardous.

The effectiveness of modern methods of induction may tempt the obstetrician to be over-enthusiastic in their use. Any intervention should carry the implication of delivery by whatever means necessary and must therefore be justifiable.

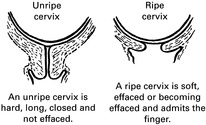

As labour approaches, the cervix normally shows changes known as ‘ripening’ so that it becomes ‘inducible’ and is then called a ‘favourable’ cervix. The condition of the cervix is the most important factor in successful induction and, where ripening has not occurred, there is a greater chance of a long labour, fetal hypoxia and operative delivery.

This is an accepted method of recording the degree of ripeness before labour (cf. the Apgar score applied to the newborn baby). It takes account of the length, dilatation and consistency of the cervix and the level of the fetal head. A score of 9 or higher is favourable.

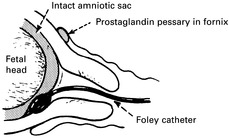

The collagen fibres of which the cervix is composed can be much softened in consistency by the local application of prostaglandin. A vaginal tablet or gel containing dinoprostone (Prostin E2) may be inserted into the posterior fornix to soften and efface the cervix. This will permit amniotomy and may even result in the initiation of labour. Increasingly the cheaper alternative of misoprostol given intravaginally is being used for ripening the cervix and also for induction of labour.

Physical methods such as the introduction of a Foley catheter through the cervical os appear to stimulate local production of prostaglandins and may also ripen the cervix.

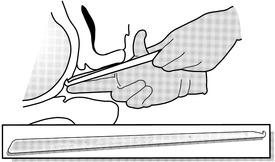

Amniotomy, using a Hollister Amnihook or other device, may be used to rupture the membranes overlying the presenting part. Care must be taken not to damage the fetal tissues. The operation may be done blindly by passing the instrument along the fingers or by direct vision using a speculum.

The procedure is carried out using an aseptic technique and sometimes sedation or even epidural anaesthesia may be required to permit adequate examination. The colour and quantity of the liquor removed should be noted. Prolapse of the umbilical cord should be excluded at the beginning and end of the procedure.

Failure to induce effective contractions

Labour may not become established after amniotomy alone and it is usual to stimulate the uterus further by intravenous oxytocin after an interval of 3 hours or so if contractions are inadequate.

This may be caused by the sudden reduction in the volume of liquor where there has been polyhydramnios.

This is not uncommon. The usual source is maternal blood from an element of forced dilatation of the cervix by the examining fingers. Occasionally it may come from fetal vessels running in the membranes (velamentous insertion of the cord). The best method of identifying the source of blood is by Kleihauer’s test, a laboratory procedure, by which a blood slide is so stained as to show the fetal cells standing out in a field of ‘ghost’ maternal cells (see Chapter 8).

This will only happen with an ill-fitting presenting part. Cord prolapse, occult or frank, should give warning signs on the fetal heart rate monitor.

This rare condition presents as severe shock of rapid onset, with intense dyspnoea and often bleeding. It is associated with amniotomy and strong uterine contractions, and must be distinguished from eclampsia, abruption, ruptured uterus, and acid aspiration. Treatment must include positive pressure ventilation, and correction of the inevitable coagulation defect. Postmortem examination of the maternal lungs will show fetal cells and lanugo.

Synthetic oxytocin by continuous intravenous infusion is commonly used after amniotomy to stimulate uterine contraction. It is also used occasionally with intact membranes, e.g. to help stabilise the fetus with a variable lie prior to amniotomy. In this circumstance care should be taken to prevent excessive uterine action which can cause amniotic fluid embolism. Like amniotomy, intravenous oxytocin is also used to augment or accelerate labour.

Synthetic oxytocin is a powerful drug and sometimes unpredictable, as uterine sensitivity can show a wide variation. It must be administered with great care by the doctor or midwife who should be present throughout.

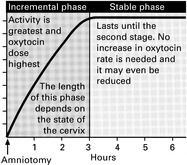

This varies with time and the progress of labour. Since too little oxytocin is useless and too much may cause fetal hypoxia or uterine rupture, it is necessary to adjust the dosage to the individual patient’s response.

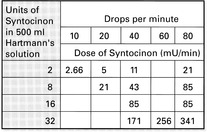

The best method of administration is by a suitable semi-automated infusion system incorporating an accurate drop counter. A solution of 2 units of Syntocinon in 500ml of Hartmann’s solution is used, beginning at a dose of 2.66mU/minute. This is increased every 15 minutes until satisfactory contractions are established.

Prolonged or excessive oxytocin administration can cause fetal hypoxia by overstimulation of the uterus. Continuous fetal heart rate monitoring is required for all patients undergoing oxytocin stimulation.

Overdosage can cause excessive, painful contractions and even a prolonged spasm (tetanic contraction). If hyperstimulation becomes evident, the infusion should be stopped to allow the uterus to relax.

An intra-uterine pressure transducer may be used in women who are difficult to assess, e.g. the obese.

The possibility of rupture must be borne in mind when using oxytocin. It is unlikely in a primigravida but has been reported. It is more to be expected in the parous woman or in the patient who has had a previous caesarean section or hysterotomy. The use of an intra-uterine pressure transducer may be advisable in such patients. Epidural anaesthesia does not mask the pain of uterine rupture but it should be used with caution.

This may result from the prolonged administration of high doses of oxytocin in large volumes of electrolyte-free fluid. This should not be an issue in labour using normal dosage of oxytocin in an agent such as Hartmann’s solution.

The progress of spontaneous labour can be speeded up by amniotomy and oxytocin infusion. By using these techniques most women can be delivered within 12 hours. Prolonged labour is thus avoided together with its possible accompaniment of maternal exhaustion, fetal distress and intra-uterine infection. Such interventions should not, however, be automatic and their indiscriminate application has aroused hostility in some mothers. If acceleration is considered desirable the reason for this should be explained and discussed with the mother.

1. Incorrect diagnosis. Patient not in labour.

2. Dysfunctional uterine activity. Common in primigravidae, rare in multiparae. Associated with occipito-posterior malposition.

3. Malposition/malpresentation.

4. Cephalopelvic disproportion.

5. Rare causes, e.g. cervical stenosis from previous cervical surgery or pelvic tumour such as fibroid or ovarian cyst.

Dysfunctional labour occurs when the cervix does not dilate despite the presence of uterine contractions. The cervix should dilate at a rate of between 1 and 2 centimetres per hour in the active phase. Progress is more rapid in parous women and dysfunctional labour is much commoner in primigravidae.

Treatment consists of escalating doses of oxytocin. This should only be used in parous women when there is no evidence of malpresentation, and even then only with caution. The dose of oxytocin should be titrated against the quality and frequency of uterine contractions.

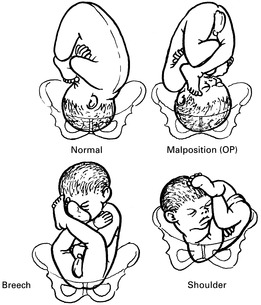

Malposition means incorrect positioning of the vertex. This includes occipito-posterior (OP) positions and deflection of the head short of brow presentation.

Malpresentation means the presence of any presenting part other than the vertex — face, brow, breech, shoulder, compound presentation.

With a malpresentation such as brow or shoulder there is a danger of obstructed labour and uterine rupture if unrecognised.