13

Abnormal growth and sex development

Chapter map

Concerns about growth feature commonly in paediatric outpatient clinics, and sometimes result in admission. You need to be comfortable in assessing normal growth so that you can identify the abnormal. Common problems include failure to thrive in young children, and short stature in teenagers. Problems of sex development are less common, but distressing. An understanding of the range of causes informs investigation and management.

13.2.2 Testicular feminization (androgen insensitivity) syndrome

13.1 Abnormal growth

13.1.1 Failure to thrive

13.1.1.1 What is failure to thrive?

This applies to a young child who is not growing well, usually for weight gain (Figure 13.1). In practice, this means:

Figure 13.1 Failure to thrive. Loss of subcutaneous fat is seen in this boy who is failing to thrive.

- Weight crossing down through two centile lines

- Weight on or below the 2nd centile line and falling away.

- Feeding problems or neglect

- Poor appetite

- Mechanical problems, e.g. cleft palate, cerebral palsy

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux, pyloric stenosis

- Feeding problems

- Food intolerance

- Cystic fibrosis

- Food intolerance (including coeliac disease)

- Chronic infective diarrhoea

- Chronic infections

- Heart failure, renal failure

- Metabolic disorder

- Constitutionally small

- Genetic syndrome, e.g. Turner’s in girls

PRACTICE POINT Common reasons for a failure to thrive referral

PRACTICE POINT Common reasons for a failure to thrive referral- Weights measured or plotted incorrectly: do not forget to allow for gestation in the preterm (<37 weeks).

- Over the first few months of life, uterine influences ‘wear off’ and the child finds his own centile for weight. This may result in tracking upwards or downwards on the centile chart, and the latter may appear as failure to thrive.

- Child drinking excessive amounts of fluid – especially milk or juice. Remedy – reduce fluid intake, especially before meals.

- Poor intake and socioeconomic deprivation.

13.1.1.2 Approach to failure to thrive

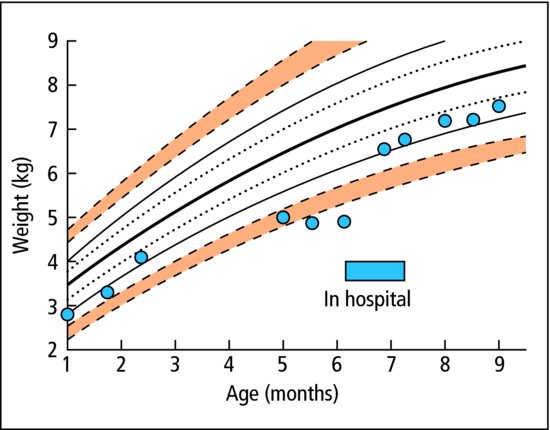

Careful history and examination are essential. Sometimes the main reason for failure to thrive is obvious – inadequate food intake or chronic vomiting or diarrhoea. Often there is no clear reason apparent at the first consultation: parents appear caring and competent, adequate food is given, and there are no clues to a particular disorder. Solving the problem is difficult, and unfocused investigation is not helpful. The parent-held child health record (the red book) gives invaluable information about growth. It is helpful to work with a dietician who will quantify intake and help with management. The health visitor can provide a reliable account of the home and whether both food and emotional nourishment are available there. A home visit can be most revealing. Sometimes the child is admitted to hospital to be fed standard amounts of food and observed to see if weight gain occurs, and to note symptoms (Figure 13.2). Investigations may be performed, looking for common problems first (see box). The single greatest challenge is to distinguish those with organic pathology from the many children with non-organic failure to thrive – an important group whose problems are social, emotional or economic in origin.

Figure 13.2 Sadie was admitted at 6 months of age with failure to thrive. In hospital she gained weight well with normal feeding and was discharged with intensive community-based support.

PRACTICE POINT Investigations to consider in failure to thrive

PRACTICE POINT Investigations to consider in failure to thrive- Urinalysis (dipstick and microscopy and culture) – for infection

- Full blood count

- Renal and liver function

- Acute phase response (ESR, CRP or plasma viscosity)

- Thyroid function

- Coeliac disease antibodies

- Chromosomes (in girls) – for Turner’s.

- Constitutional

- Delayed puberty

- Defects of nutrition, digestion or absorption

- Social and emotional deprivation

- Most malformation syndromes

- Chronic disease (e.g. renal insufficiency, malignancy)

- Genetic syndromes (e.g. Turner syndrome in girls)

- Endocrine (e.g. deficiency of thyroid or growth hormone)

- Iatrogenic (e.g. long-term steroid therapy)

- Disorders of bone growth (e.g. skeletal dysplasias).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree