Fig. 1.1

AFS classification based on Müllerian anomalies

A type: bilateral developmental anomalies. (1) Vaginal agenesis, complete; (2) vaginal agenesis, partial (upper or lower); (3) cervical aplasia; (4) cervical hypoplasia; (5) tubal aplasia; (6) uterine aplasia; (7) uterine hypoplasia (with or without uterine cavity); (8) combined dysplasia

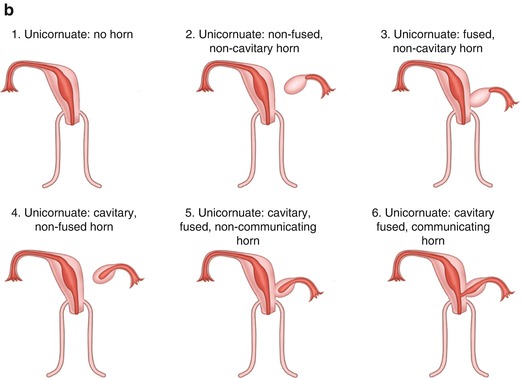

B type: unilateral developmental anomalies. (1) Unicornuate, no horn; (2) unicornuate, non-fused, non-cavitary horn; (3) unicornuate, fused, non-cavitary horn; (4) unicornuate, cavitary, non-fused horn; (5) unicornuate, cavitary, fused, noncommunicating horn; (6) unicornuate, cavitary, fused, communicating horn.

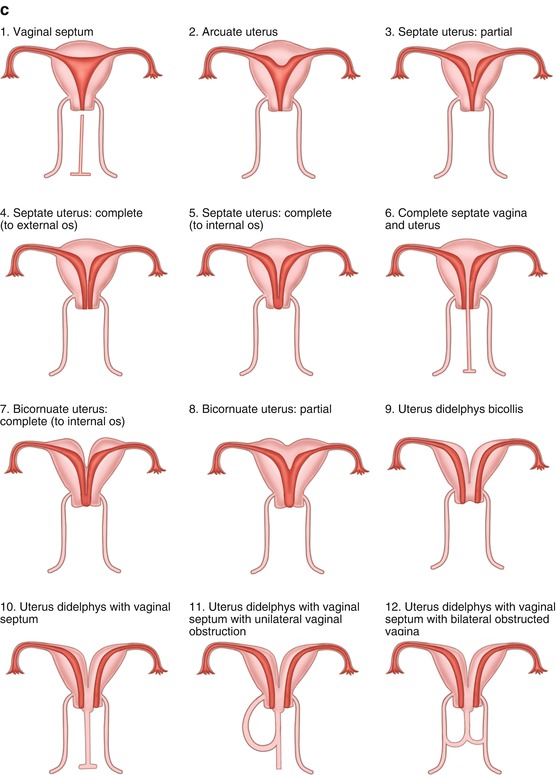

C type: fusion anomalies. (1) Vaginal septum; (2) arcuate uterus; (3) septate uterus, partial; (4) septate uterus, complete to external os of the cervix; (5) septate uterus, complete, up to internal os of the cervix; (6) complete septate, vagina, and uterus; (7) bicornuate uterus, complete to internal os of cervix; (8) bicornuate uterus, partial; (9) uterus didelphys bicollis; (10) uterus didelphys with the vaginal septum; (11) uterus didelphys with the vaginal septum, with unilateral vaginal obstruction; (12) uterus didelphys with the vaginal septum with bilateral obstructed vagina

1.2.1.2 Acién Classification of Reproductive Tract Anomalies

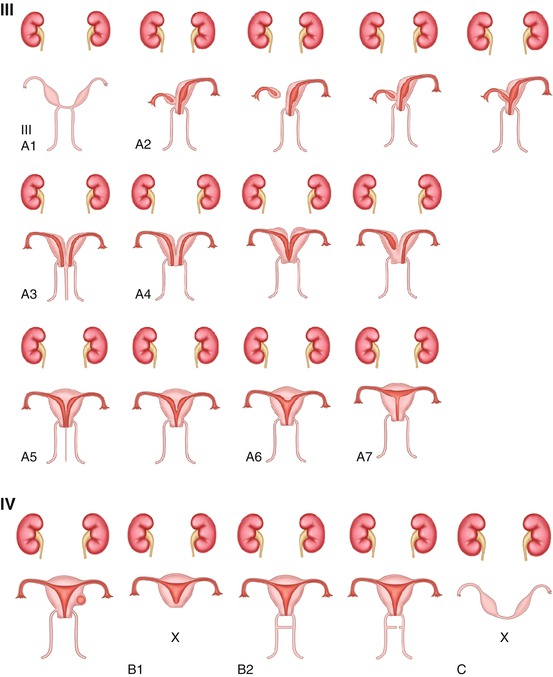

In 2011, Acién [3] conducted a systematic review of relevant articles of reproductive tract anomalies from 64 full-text articles and more than 300 related clinical papers in the literature. Based on the experience gained from the application of the current classification systems and the appropriate treatment, he updated the female urogenital tract anomalies in accordance with the etiopathogenesis and proposed a new embryological-clinical classification of female reproductive tract anomalies. The system also considers both Müllerian and renal tubular developmental anomalies (Fig. 1.2), but his classification system has only been published for a short time and has not been widely used.

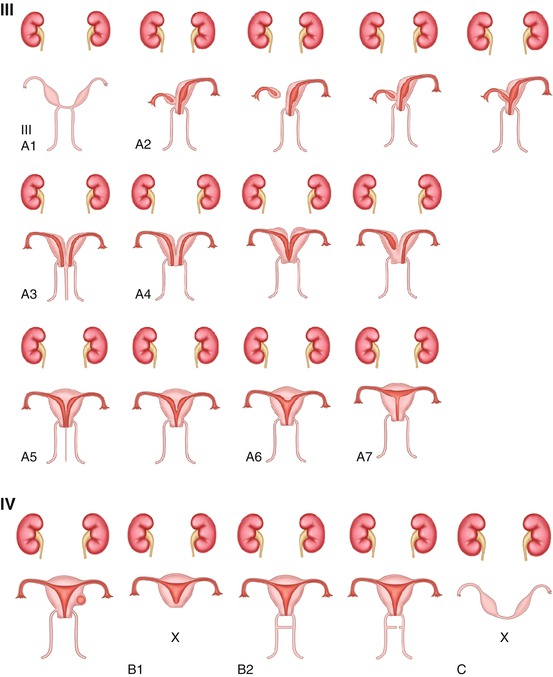

Fig. 1.2

Acién classification of reproductive tract anomalies

1.2.1.3 The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the European Association for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) Classification of Female Reproductive Tract Anomalies

In 2013 the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the European Association for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) proposed a new classification system based on anatomy. Anomalies are classified into the following main classes from the same embryological origin: the uterus, cervix, and vagina [4]: (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3

ESHRE/ESGE – uterine anomalies

1.2.2 Common Reproductive Tract Anomalies

The current classifications of reproductive tract anomalies vary with advantages and disadvantages for each classification. Among them, there are many various nomenclatures, leading to a lot of confusion and overlapping. Hereby we describe some common reproductive tract anomalies and their clinical manifestations as follows.

1.2.2.1 External Genital Anomalies

The most common female external genital anomaly is the congenital hymen anomaly.

Congenital Hymen Anomaly

The hymen is a layer of mucosal membrane located at the vaginal opening, with squamous epithelium covering on its outer and inner surfaces. In between these surfaces it contains connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerve endings. During its development, abnormal cavity formation at the urogenital sinus will develop into various anomalies which include the imperforate hymen, microperforate hymen, septate hymen, cribriform hymen, etc. (Fig. 1.4).

Fig. 1.4

Congenital anomalies of the hymen

Imperforate hymen is a rare genital anomaly, also known as nonporous hymen. The incidence of imperforate hymen is about 0.015 %. Imperforate hymen mainly obstructs the discharge of vaginal secretions. It may be asymptomatic at childhood due to minimal vaginal secretions, but at puberty, as both the vaginal and cervical secretions gradually increase, they accumulate in the vagina and lead to a sense of heaviness in the lower abdomen. After menarche, as the menstrual blood cannot drain out, it accumulates in the vagina forming a vaginal hematoma after several menstruations. Subsequently, it may lead to uterine and tubal hematomas, and eventually retrograde menstrual flow will enter into the pelvic cavity forming pelvic hematomas. Clinical symptoms are cyclical lower abdominal pains which progressively increase in intensity. On gynecological examination a bulging hymen can be seen, with a purple blue surface; on rectal examination, a vaginal mass bulging into the rectum is felt as a palpable pelvic mass. With a finger in the rectum, the pressing on the vaginal mass will make the bulging hymen more obvious. Ultrasound scan may show accumulated fluid in the vagina and even in the uterine cavity.

The clinical manifestations in patients with imperforate hymen or micropore hymen would vary according to the absence or sizes of the pore holes in the hymen. Some patients have periodic menstruations with moderate amount of menstrual blood outflow, but a lot of blood still accumulates in the vagina; sometimes these periods are irregular; some patients present with delayed menarche, with complaints of periodic abdominal pain, dyspareunia, and smelly vaginal discharge due to poor vaginal drainage. Similar to imperforate hymen, micropore hymen can cause the reflux of vaginal secretions and blood into the peritoneal cavity forming a pelvic mass. The micropore openings in the hymen may serve as communicating channels between the vagina and the outside, through which bacteria will enter and exit, leading to recurrent urinary tract infection and more commonly pelvic infection or abscess.

1.2.2.2 Vagina Anomalies

Vaginal Agenesis

Vaginal agenesis is also known as MRKHs (Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser) syndrome which includes congenital absence of the uterus and vagina. It is a kind of functional defect in the reproductive tract characterized by no reproductive ability. At present, the etiology is unclear. In animal models, it could be demonstrated that WNT4 gene suppresses male gonadal differentiation and ovarian androgen secretion; the absence of this gene might be related to this disorder [5].

Congenital vaginal agenesis is often accompanied by cervical or uterine abnormalities; 7–10 % of these patients have rudimentary uterine horn or cervical aplasia (Fig. 1.5), while the majorities have normal ovarian function. Seventy-eight percent of patients have normal uterus, 16 % with ovaries outside the pelvis, and 6 % with unilateral abnormal ovarian development [11]. These patients are often associated with other nongenital anomalies. Twenty-five to fifty percent of patients have urinary tract anomalies, including pelvic kidney or unilateral renal agenesis; 10–15 % also have skeletal anomalies mainly spinal deformities. Other rare anomalies include congenital heart disease, hand anomalies, deafness, cleft palate, and inguinal hernia.

Fig. 1.5

Vaginal agenesis. (a) With rudimentary horns. (b) With cervical aplasia

Clinical manifestations are primary amenorrhea and sexual difficulties. Generally the patient has only a primitive uterus without periodic abdominal pain. Physical examination shows normal physical appearance, with normal secondary sexual characteristics and external genitalia, but there is no vaginal opening or only a shallow concave at the posterior part of vestibule. Occasionally there is a short vagina with a closed end.

Agenesis of the Lower Vagina

In the lower vaginal agenesis (Fig. 1.2 2), the upper vagina, cervix, and uterus are normal, but it is often associated with external genital anomalies. The clinical manifestations are primary amenorrhea, periodic abdominal pain, etc. Because the endometrium functions normally, these symptoms can occur early. Pelvic examination reveals a low-positioned pelvic mass, located in front of the rectum. Often treatment can be offered timely, because their symptoms present early similar to the imperforate hymen. On examination, there is no vaginal opening and the mucosal surface of the posterior vestibule shows normal color without any outward bulging. Digital rectal examination shows a palpable mass protruding into the rectum, but at a higher position than that in the imperforate hymen. It is also associated with lesser blood reflux into the peritoneal cavity causing pelvic endometriosis.

Transverse Vaginal Septum

It is caused by the failure to the fusion of the end the paramesonephric ducts which either do not open up or only partially open together with the urogenital sinus. The incidence rate is about 1/30,000 to 1/80,000 [7]. This condition is rarely associated with urinary tract and other organ abnormalities. The septum can be located in any part of the vagina; 46 % occurred at the upper part, 35–40 % at the middle, and 15–20 % at the lower part of the vagina. The septal thickness is usually less than 1 cm. If there is no hole in the septum, it is a complete transverse septum. If there are some small holes, it is an incomplete transverse septum (Figs. 1.2 (IIIB2) and 1.6). Transverse vaginal septum at the upper end of the vagina is often an incomplete septum, while the one at the lower end is often a complete septum.