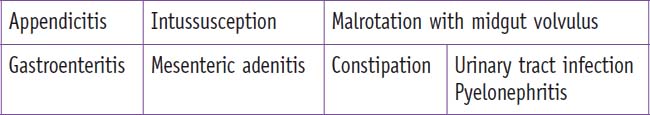

Chapter 94 Abdominal Pain (Case 51)

Patient Care

Clinical Thinking

• A careful history and physical examination remain the cornerstones of assessment of the acute abdomen. When the patient is too young to provide a history, it is obtained from parents or adult caregivers.

• An important first step is to reassure the patient and family that the examination will be performed gently. Distracting the patient during the physical examination will often be helpful.

• If the patient has systemic manifestations of his/her illness, then resuscitative management should be initiated even while the diagnosis is in the process of being determined.

• The use of CT to evaluate patients with abdominal pain has become quite prevalent in adults. This may not, however, be the best practice in pediatrics, as radiation may pose a long-term risk of cancer.

History

• Determine the location, onset, duration, severity, and type of pain. Is it constant or episodic? Has the pain shifted in location?

Physical Examination

• A complete examination is performed looking for signs and symptoms of inflammation and hypovolemia (e.g., prolonged capillary refill). The examination should also include attention to nonabdominal conditions that can present as abdominal pain (e.g., streptococcal pharyngitis, lower lobe pneumonia.)

• A detailed abdominal examination includes identifying the point of maximal tenderness. When palpating, the examination should begin away from the point of maximal tenderness and work toward tender areas. Focal peritoneal findings (tenderness to palpation and percussion, guarding, and rebound) may be present. Generalized peritonitis may present with more diffuse abdominal pain; in generalized peritonitis diffuse guarding would be expected. In advanced peritonitis the abdomen may appear “rigid.”

Tests for Consideration

• Complete blood count (CBC): A leukocytosis, especially with a left shift, suggests an inflammatory process $40

• Stool studies (culture, ova, and parasites): If persistent diarrhea, gastroenteritis presentation $120

Clinical Entities: Medical Knowledge

| Appendicitis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | The appendiceal lumen is initially obstructed (presumably by stool), leading to inflammation in the appendiceal wall; this leads to edema and bacterial overgrowth, resulting in erosion of the mucosal surface. This allows bacterial translocation, inflammation, ischemia, and ultimately perforation of the appendix with release of fecal contents and bacteria, leading to peritonitis. |

| TP | Classically, periumbilical abdominal pain precedes vomiting and is associated with low-grade fevers and anorexia. As the inflamed appendix makes contact with the peritoneum, the pain “migrates” from the periumbilical area and pinpoint tenderness is noted at the McBurney’s point in the right lower quadrant (RLQ). If the appendix lies in an atypical orientation, the area of referred pain may be offset from the RLQ. |

| Dx | The diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion and supported by examination findings, laboratory test results, and imaging. An elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and absolute neutrophil count support this diagnosis. An elevated C-reactive protein level may also be an early marker for acute appendicitis, but sensitivities and specificities are not superior to WBC alone.1 Urinalysis may demonstrate pyuria, hematuria, and/or bacteriuria. Abdominal pain films are not specific for acute appendicitis. An appendicolith is present in 10% of studies. CT studies with contrast or an ultrasound are preferred imaging studies. Ionizing radiation exposure with ultrasound, however, is operator-dependent and patient body habitus. |

| Tx | Intravenous fluids are administered for dehydration and third space losses. Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated in early appendicitis, for wound infections or intra-abdominal abscess.2 Finally, can be performed depending on the surgeon’s preference. In children, perforated appendicitis with intra-abdominal fluid and a suspected appendiceal phlegmon or abscess is often treated with hospitalization and IV antibiotics; “interval appendectomy” is usually performed 6 to 8 weeks later when the child has recovered from the acute illness. See Nelson Essentials 129. |

| Intussusception | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Intussusception is an obstruction caused by bowel telescoping in on itself. The intussusceptum tunnels into the intussuscipiens, pulling mesentery and vasculature into the distal lumen. Venous and lymphatic congestion develops, causing intestinal edema, and possibly ischemia from obstructed arterial flow. |

| TP | Typical patients are 3 to 24 months old, but can be up to 6 years and present with episodes of sudden-onset severe, colicky abdominal pain with irritability and drawing up of the knees. The patients are often lethargic between episodes. Patients often present following a viral prodrome. The classic triad of colicky pain, vomiting, and bloody mucous stool (current jelly stool) is relatively uncommon.3 |

| Dx | A sausage-shaped mass in the RUQ may be palpable. Stool for occult blood may be positive. An obstruction series may be normal or may reveal a mass effect, usually in the RUQ with distended proximal bowel loops. The preferred study is an abdominal ultrasound, which may demonstrate a “bull’s-eye” or “coiled spring” representing the intussusception. |

| Tx | A contrast enema is diagnostic and is therapeutic in 80% to 90% of cases. Air reduction is preferred because of a higher success rate and fewer complications. If used, contrast must be refluxed into the terminal ileum to ensure complete reduction. There is a 10% risk for recurrence after successful reduction by contrast enema. When an enema fails or if peritonitis is present, surgery is indicated. Surgery may consist of simple manual reduction or may require resection of an identified lead point or necrotic bowel. Some centers administer prophylactic antibiotics before contrast enema in the rare event of perforation during reduction. See Nelson Essentials 129. |

| Malrotation With Midgut Volvulus | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Malrotation results from the improper rotation of the intestines during embryogenesis. Improper fixation of the mesentery of the bowel to the posterior abdominal wall causes it to twist and obstruct, causing a volvulus. |

| TP | Malrotation with volvulus may occur in any infant or child. Presentation is usually bilious emesis and abdominal pain. The pain is severe and constant and can be associated with gross blood from the rectum—an indication of significant ischemia and possible necrosis of the bowel. Older children (>1 year) constitute 25% of these cases. On examination, the abdomen may be distended and diffusely tender. |

| Dx | Suspect malrotation in all children with sudden onset of bilious vomiting, severe abdominal pain, and hemodynamic instability. Clinically unstable patients should proceed directly to surgery for exploratory laparotomy. Stable patients are evaluated with plain radiographs, upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast study, barium enema, or ultrasound. Plain films may be normal or may demonstrate a gasless abdomen or mild intestinal dilation. Especially concerning is the malpositioning of an orogastric or nasogastric tube in the duodenum or a “double bubble” sign consistent with duodenal obstruction. An upper GI study is the gold standard for visualization of the duodenum and the position of the ligament of Treitz. In malrotation, the ligament of Treitz may appear on the right side of the abdomen, or the duodenum may have a “corkscrew” appearance. Ultrasound may illustrate an abnormal position of the superior mesenteric vein or a dilated duodenum as a result of obstruction by Ladd bands.4 |

| Tx | Fluid resuscitation should be administered. A nasogastric or orogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are initiated to cover for bowel flora. Surgical correction is urgently required and is life-saving. See Nelson Essentials 129. |

| Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Gastroenteritis is caused by a number of common pathogens, including both viruses and bacteria. |

| TP | The typical patient presents with vomiting followed by diarrhea. However, there may be only vomiting or only diarrhea. Stools may contain blood, more commonly with bacterial enteritis. Patients may have abdominal pain and signs of dehydration. |

| Dx | A history of sick contacts, travel, antibiotic use, and possible seafood ingestion should be obtained. The degree of dehydration should be assessed and serum electrolytes should be checked in severely dehydrated patients. Stools can be sent for analysis for fecal leukocytes, culture, and ova and parasites. |

| Tx | Mild to moderate dehydration is managed with oral rehydration with commercially available pediatric oral electrolyte solutions, which can often be done at home. For severe dehydration, significant emesis or high stool output may prevent adequate oral rehydration, making intravenous rehydration necessary. Antibiotics may be indicated for patients with diarrhea caused by Clostridum difficlle, Shigella, or Salmonella. See Chapter 34, Diarrhea, and Chapter 92, Dehydration. See Nelson Essentials 112. |

| Mesenteric Lymphadenitis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Mesenteric lymphadenitis is inflammation of the mesenteric (usually ileocolic) lymph nodes, and may be due to either bacterial or viral pathogens. It may occur with streptococcal pharyngitis, and in children is more commonly associated with a primary enteric pathogen. |

| TP | The presentation is variable and may include fever, RLQ pain, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally diarrhea. The site of tenderness may shift when the patient changes position (in contrast to appendicitis, where it usually remains in the same location). The patient may have pharyngitis. |

| Dx | Leukocytosis is common. A throat culture for Streptococcus should be obtained if pharyngitis is present. The diagnosis is generally one of exclusion. Ultrasonography with graded compression or CT may be useful in the diagnosis and in excluding appendicitis. |

| Tx | The disease is generally self-limited; hospital admission may be indicated for rehydration and for serial examinations to rule out an early appendicitis that may be missed on diagnostic imaging. |

Urinary Tract Infection/Pyelonephritis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree