Chapter 17 Abdominal Pain

ETIOLOGY

EVALUATION

How Do I Evaluate Acute Abdominal Pain?

Acute abdominal pain is defined as a condition of recent onset, with characteristics that indicate an urgent need for diagnosis and management. You must obtain a precise history, examine the child carefully, and, finally, order appropriate tests. Table 17-1 summarizes the information you must gather to evaluate the child with acute abdomen. Not all of the studies listed in Table 17-1 must be performed in all patients. If your history and examination lead you directly to a particular diagnosis, such as constipation, you may treat it directly.

Table 17-1 Evaluation of the Child with Acute Abdominal Pain

| History | |

| Onset | Sudden vs. gradual, preceding injury, prior episodes |

| Associated symptoms | Fever, nausea, dysuria, diarrhea, constipation, bloody stools or emesis, cough |

| Location of pain | Periumbilical, epigastric, right lower quadrant, left lower quadrant, well-localized or vague |

| Nature of pain | Aching, cramping, dull, sharp, burning, constant vs. colicky |

| Progression | Worsening, improving, changing location |

| Physical Examination | |

| General | Hydration, appearance of toxicity, growth and weight gain |

| Chest | Crackles, rhonchi, wheezing, tenderness of musculoskeletal structures |

| Abdomen | Distention, bowel sounds, tenderness (location, severity, rebound, superficial vs. deep), mass |

| Rectal examination | Fecal impaction, occult blood, pelvic tenderness, extrinsic mass |

| Laboratory/Radiologic Evaluation | |

| CBC | Evidence of infection or inflammation |

| ESR and CRP | Evidence of inflammation or infection |

| Amylase, lipase | Pancreatitis |

| GGT | Bile duct obstruction or injury |

| ALT, AST | Hepatitis |

| Urinalysis | Urinary tract infection, hematuria (stones, obstruction) |

| Plain x-rays | Bowel gas pattern, evidence of obstruction, free peritoneal air, constipation, kidney stones, appendiceal fecalith |

| CT or ultrasound | Appendiceal abscess, intussusception, gallstones, pancreatitis, bile duct obstruction, kidney stones, renal anomalies |

| Barium enema | Intussusception, malrotation, less useful for appendicitis |

ALT, Alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; CBC, complete blood count; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase.

What Causes Recurrent Abdominal Pain?

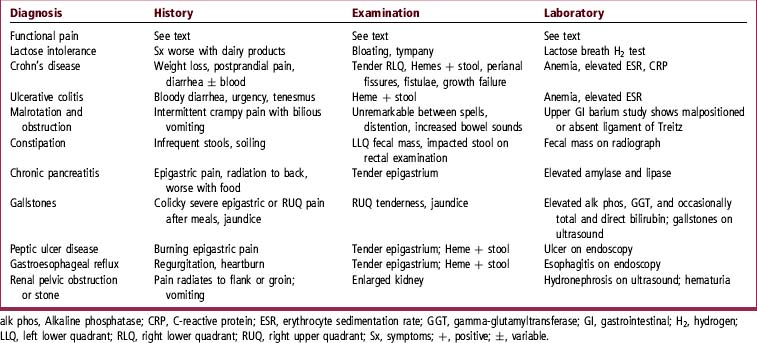

Table 17-2 lists most of the more common causes plus features on history, physical examination, and laboratory testing that may suggest the diagnosis.

What History Helps Evaluate RAP?

You will need to define accurately the nature and time course of the pain, determine what exacerbates and relieves it, identify associated symptoms, and decide whether or not indications of serious underlying illness are present. It is also important to assess whether genetic or environmental factors may be playing a role. It is not useful to approach the child with the attitude that the abdominal pain may not be “real.” A child with pain is in need of your assistance, whether the cause is a significant underlying illness or a purely functional disorder. Table 17-3 lists questions that you should ask of every patient.

Table 17-3 Historical Data for Abdominal Pain

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|