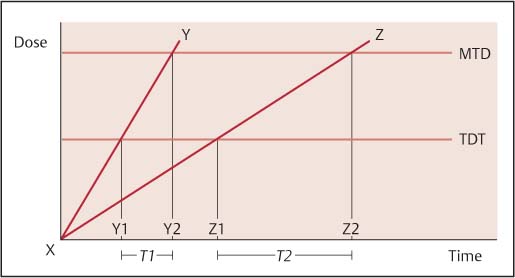

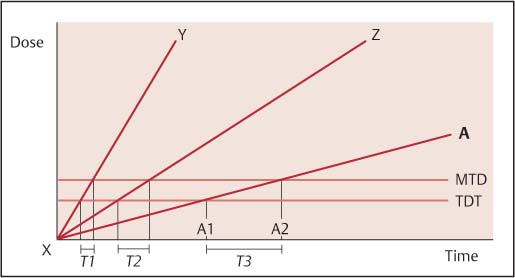

4 A Model for Judging the Dosage Needs of Patients In mainstream medicine, it is generally well understood that there is an optimal dosage range for a particular drug to be effective. The concentration of the drug in the blood should lie roughly between two values for it to be effective. Below the lower value, the drug is less effective or ineffective and above the upper value the drug is in too high a concentration and can cause unwanted side-effects or lead to overdose of treatment. This general idea is quantitatively based, where the optimal dose range is often based on body mass and the upper and lower dose ranges are numerical values. But it is possible to extend this idea to a more qualitative illustration of dosage needs. I say that it is qualitative since we have no laboratory value to measure. We can make qualitative estimates of need only. The following ideas are extensions of explanations that Yoshio Manaka made about dose of treatment, in relation to intensity of stimulation delivered (Manaka, Itaya, and Birch 1995, pp. 118–119). When a therapy reaches the therapeutic dose threshold (TDT), it starts to have its expected therapeutic effects. If the dose of the treatment builds up too much so that it crosses the maximum therapeutic dose (MTD), the patient may start to experience unwanted side-effects due to over-treatment. With a medication, the dose taken and the intervals between times that the medication is taken are often matched, so that the concentration of the medication in the blood remains in the optimal dose range—between TDT and MTD in Fig. 4.1. With an acupuncture treatment, we interpret this figure a little differently. Two treatments, Y and Z are charted. Both treatments start from point X. Treatment Y has a relatively high intensity stimulation, the dose build-up is quicker than treatment Z, which delivers a milder intensity stimulation. Y1 and Z1 are the times that treatments Y and Z cross the TDT respectively and Y2, Z2 are the times that treatments Y and Z cross the MTD respectively. The time that the practitioner of treatment Y has to judge the correct dose of treatment is T1 (the distance between Y1 and Y2), while the time that the practitioner of treatment Z has to judge the correct dose of treatment is T2 (the distance between Z1 and Z2). Since T2 is larger than T1, we can say that the risk of reaching overdose of treatment is less with treatment Z than with treatment Y. It is therefore easier and safer to administer treatment Z. Of course, this is a gross simplification. For example, what about a therapy like homoeopathy where the lower the physical dose of treatment (the more diluted), the higher the therapeutic dose (energetic)? Manaka hinted at these things with his X-signal system model of acupuncture (Manaka, Itaya, and Birch 1995, pp. 118–119). A lower intensity form of acupuncture (as physical stimulus) is not necessarily a lower dose treatment since at very low energy content (very low-intensity stimulus treatment) the more the energy level content of the treatment approaches or approximates the energy level content of the physiological systems, the more it could be therapeutically active (i.e., the less the physical stimulus, sometimes the stronger the signal system mediated therapeutic effects). See Manaka et al. (1995) for details of this idea. But for the purposes of the model here, if we assume that within the context of a particular treatment model the above graphical representation of the doses of treatment are applicable, then it is possible to illustrate what happens with sensitive patients. Fig. 4.1 Dose levels for normal sensitivity patient with different intensities of treatment (Y, Z). (TDT, therapeutic dose threshold; MTD, maximum therapeutic dose.) A sensitive patient will typically show two characteristic differences compared with the typical patient. First, the TDT drops and can be very low, meaning that it takes very little to start triggering change. Second, the width of the optimal dose range narrows considerably, so that it takes very little more therapeutic input after the TDT is crossed for the treatment to cross the MTD. Of course, it is possible that the sensitive patient may be very healthy, where the TDT is very low, but the MTD is not lower, so that the optimal therapeutic range remains very wide. These are our most ideal patients, for whom one hardly has to do anything to start triggering healthful effects and for whom one can do a lot more without any adverse effects. These patients are, in my experience, very rare. Most sensitive patients who show the lowered TDT also show a lowered MTD. This can be seen graphically in Fig. 4.2. If treatment Y from Fig. 4.1 were administered on this sensitive patient, the time to judge proper dose, T1, is very small and overdose of treatment is hard to avoid. Even treatment Z, which has a lower intensity of treatment, would be difficult, since T2 is also very small. One has to administer a treatment that is extremely low dose, has a very low intensity, and is mild and gentle: treatment A, if one wants to have any chance of avoiding overdose of treatment on this patient. Here the time to judge treatment dosage (distance from A1 to A2), T3, is much larger than T1 or T2. The use of a very low intensity treatment allows the dose to build up much more slowly, so that one has more time (T3) to make the clinical judgment to stop treatment. This idea is important and clinically very helpful. It is necessary to assume that all children, even teenagers, fit this profile of the sensitive patient. Certainly, all babies and smaller children fit this profile, but even older children can. Thus, at least until one has evidence to the contrary, one should approach even older children as being more sensitive. We will discuss below the subject of how to adjust techniques in order to increase or decrease dose and how to match this judgment to each individual child. Fig. 4.2 Dose levels for the very sensitive patient (child) with different intensities of treatment (Y, Z, A). (TDT, therapeutic dose threshold; MTD, maximum therapeutic dose.) There is a long-standing tradition in Asia that addresses the need to regulate one’s emotions. This is an important theme in Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist thinking. The early medical literature in China followed this theme when it discussed how all emotional expressions represent some kind of disorder of qi movement or function in the body, and classified a number of common emotions in relation to the primary organs (zang) in the body (Chiu 1986; Matsumoto and Birch 1988; Unschuld 2003; Birch, Cabrer Mir, and Rodriguez, in preperation). These dominant emotions were said to injure their corresponding organ and each was described in relation to particular qi disturbances. The emotions were discussed in relation to health problems. In larger social discourse, the ability to manifest correct behavior and help regulate oneself is necessary to regulate one’s emotions. Babies are unable to talk. Instead, they express themselves via their emotions. Of course, we see different manifestations of this: a more liver-related expression is an angry one that manifests with a lot of explosive crying and an inability to settle, whilst a more kidney-related expression is one of jumpiness, of fear reactions. But the important issue is that babies and small children have no ability to regulate their emotions. Communication in babies and smaller children is achieved by emotional expression. Thus, in babies and small children, many forms of normal healthy communication can trigger disturbances in qi movements and functions in the body. This has immediate consequences: it tends to make babies and children very sensitive as their qi is involuntarily changed easily. Thus, one of the goals of treatment is to try, as much as possible, not to cause the child emotional distress. As therapists we are trying to help regulate the qi of the patient, but if what we do causes emotional distress so that the child starts crying and becomes very upset, this can counter the effects of our treatment and even trigger unexpected reactions. Further clinical implications of this for the treatment of babies and children are discussed in later chapters. This same issue holds for all children, even teenagers. Sometimes we come across a 4-year-old child who we all agree is “very mature.” By this we mean that the child is more in control of his or her emotions than other children the same age, and it is easier to deal with that child. Conversely, we can have a 15-year-old physically well-developed child who is emotionally very unregulated and we might describe that child as “immature.” It can be difficult dealing with the child as he or she is unable to control his or her responses to things. The 4-year-old can handle things better than other 4-year-olds, whilst the 15-year-old cannot handle things well in comparison to other children of the same age. This shows in the responsiveness to treatment and how one handles the child. I will give various examples of this later, showing how with a good understanding of this, one can demonstrate treatment effectiveness in how one approaches and deals with the child, and with how one adjusts one’s treatment techniques. For example, below the age of 5 we prefer not to have to insert any needles, but beyond the age of 5 we start to think about how and whether we need to insert needles. This is a double-edged idea. On the one hand, needling is frightening, and thus potentially more distressing to a more immature (younger) child. On the other hand, needling is a bigger dosage than the standard shonishin techniques described below, and thus it is more difficult to control the treatment. However, there are always exceptions that we uncover—the emotionally mature 4-year-old can (with good needling techniques) handle being needled better than the immature 15-year-old. There are a number of consequences of this for application of treatment with children. First of all, try not to upset the child during treatment. This requires attention to several details. Take time over the course of treatment to make sure that the child is comfortable with you and what you are doing. Don’t try to force things unless necessary. The therapeutic relationship is very important in acupuncture treatment, especially with children. Some children will like you and what you are doing immediately; others take time to demonstrate trust, especially if they have been chronically ill and have seen many health care providers, or have had many treatments. It is thus advisable to take the time over the first treatment to make sure that the child is settled, comfortable with you, and not frightened by you. This is not only to do with your manner and behavior; it is also to do with how you apply your treatment techniques, how you handle the child. Thus, we modify how we apply treatment techniques so that they are not distressing, we try to choose only those techniques that can be applied without the child becoming upset. One pediatric specialist in Japan even recommends not making eye contact with the child during treatment since babies and small children can be easily frightened. Although this last idea can be useful with some babies and small children it is not always advisable. There are some with whom it is better to maintain eye contact to help them feel secure and comfortable. When we apply techniques that could be distressing, such as inserting needles, we do it in such a way that the child does not feel pain or discomfort. Likewise, if one needs to bleed a jing point (which is not often required) it needs to be done in such a way that not only does the child feel nothing but they also see no blood. This requires the use of needling techniques that are guaranteed to be painless and sensationless. I discuss methods that allow one to needle like this in Chapter 15. A consequence of this basic rule is that we have to be careful how we choose to apply some of our treatment techniques. It does not help to try negotiating with a small child who is frightened of needles, to insert needles. First, get discreet permission from the parent and then needle in such a way that the child cannot feel or see what you have done. On older children this can be trickier. The example of George below shows the successful needling of a 6-year-old. Example George had been having problems with repeatedly catching colds, and prolonged periods of bronchitis over the last year. He had tried homeopathy but the current episode of bronchitis was not clearing up, and the symptoms of coughing, congested lungs, and disturbed sleep had been going on for a few weeks. He agreed to come to try acupuncture only because he had been promised that “Steve will never insert any needles in you.” A typical 6-year-old with these symptoms will usually benefit quickly from a few strategically inserted needles, but this was not an option. For the first visit, the task was to make sure that he liked what was being done and that it was comfortable and not frightening. I applied a simple version of the non-pattern-based root treatment described in Chapter 7. I found hard knots around BL-13 on both sides, and left press-spheres1 on these points. __________________ 1 There is much more information in Chapter 12 on using press-spheres, but briefly, the press-sphere or ryu is a stainless-steel ball bearing usually no bigger than 2 mm in diameter. It is secured to a circular piece of tape that can then be pressed onto the skin. In Japan, the press-spheres are placed mostly on body points that are particularly sore and retained for a maximum of 3 to 4 days. He came back a week later and there had been some improvement in his symptoms, albeit slight. He was still very wary about the needles and nervous that I might insert some. I repeated the treatment at a slightly higher dose. He returned a week later, with a further slight improvement in his symptoms, but this time he was more settled with me and less worried that I was going to use needles on him. After doing the basic treatment, I turned my back on him while I prepared a 3 mm-long intra-dermal needle held with tweezers. I turned to him, putting the tiny needle in front of him and asked “Is it alright if I insert this on your back?” He laughed and replied “You can do what you want with that!” I then inserted two intra-dermal needles at the knots at left and right BL-13, giving instructions to his mother on how to care for them. When he returned for treatment a week later the coughing, lung congestion, and sleep were much better. He took his clothes off, threw himself onto the treatment bed and said “Needle me!” After this I could use a larger variety of treatment techniques to help him fully recover, and to help make sure that the next colds would not linger on as chronic bronchitis.

The Therapeutic Dose—A Conceptual Model

The Sensitive Patient

Explanations of Increased Sensitivity

A Model for Judging the Dosage Needs of Patients

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree