Where does the rubber meet the road and lead to pathology and disease during the course of life?

First, although genetics is beginning to provide a much better understanding of the etiologic factors in poor health, it probably accounts for only about one third of the direct causes. For example, person X with gene A has a disease, but person Y with the same gene does not. Clearly there is more to human development and disease risk than one’s genetic makeup. It is thought that factors such as poverty or abnormal health behaviors and environmental conditions can influence the expression of gene A. This may occur directly, or these factors may activate another gene, A-2, downstream, which may then affect gene A. The process whereby human cells can have the same genomic makeup but different characteristics is referred to as epigenetics. It is now thought that the effect of harmful behaviors and our environment on the expression of our genes may account for up to 40% of all premature deaths in the United States. Two of the top behavioral factors related to this premature death rate are obesity (and physical inactivity) and smoking. Environmental exposures to metals, solvents, pesticides, endocrine disruptors, and other reproductive toxicants are also major concerns.

Second, in human biology, a phenomenon called adaptive developmental plasticity plays a very important role in helping to adjust behavior to meet any environmental challenges. To understand human development over time (a life-course perspective), one must first understand what is normal and what adverse circumstances may challenge and then change normal development in the fetus. These protective modifications of growth and development may become permanent—programmed in utero to prevent fetal death. The price the fetus may pay in the long run, however, for short-term survival is a vulnerability to conditions such as obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, and even a chronic disease such as diabetes.

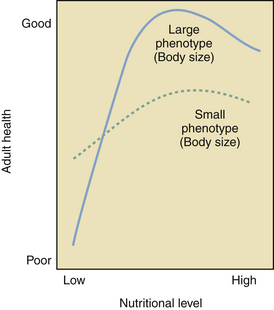

In relation to individual X and individual Y with the same genomic makeup but different in utero environmental influences, metabolic changes that may be initiated in utero in response to inadequate nutritional supplies (Figure 1-1) can lead to insulin resistance and eventually the development of type 2 diabetes. These adaptive changes can even result in a reduced number of nephrons in the kidneys as a stressed fetus conserves limited nutritional resources for more important in utero organ systems. This can then lead to a greater risk for hypertension later in life. This series of initially protective but eventually harmful developmental changes was first described in humans by David Barker, a British epidemiologist, who carefully assessed birth records of individuals and linked low birth weight to the development of hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and stroke later in life. The association among poor fetal growth during intrauterine life, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease is known as the Barker hypothesis. The process whereby a stimulus or insult, at a sensitive or critical period of fetal development, induces permanent alterations in the structure and functions of the baby’s vital organs, with lasting or lifelong consequences for health and disease, is now commonly referred to as developmental programming.

Third, another important concept in the life-course perspective is allostasis, which describes the body’s ability to maintain stability during physiologic change. A good example of allostasis is found in the body’s stress response. When the body is under stress (biological or psychological), it activates a stress response. The sympathetic system kicks in, and adrenalin flows to make the heart pump faster and harder (with the end result of delivering more blood and oxygen to vital organs, including the brain). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is also activated to produce more cortisol, which has many actions to prepare the body for fight or flight.

But as soon as the fight or flight is over, the stress response is turned off. The body’s sympathetic response is counteracted by a parasympathetic response, which fires a signal through the vagal nerve to slow down the heart, and the HPA axis is shut off by cortisol through negative feedback mechanisms. Negative feedback mechanisms are common to many biological systems and work very much like a thermostat. When the room temperature falls below a preset point, the thermostat turns on the heat. Once the preset temperature is reached, the heat turns off the thermostat. Stress turns on the HPA axis to produce cortisol. Cortisol, in turn, turns off the HPA axis to keep the stress response in check. The body has these exquisite built-in mechanisms for checks and balance to help maintain allostasis, or stability through change.

This stress response works well for acute stress; it tends to break down under chronic stress. It works well for stress one can fight off or run from, but it doesn’t work as well for stress from which there is no escape. In the face of chronic and repeated stress, the body’s stress response is always turned on, and over time will wear out. The body goes from being “stressed” to being “stressed out”—from a state of allostasis to allostatic overload. This describes the cumulative wear and tear on the body’s adaptive systems from chronic stress.

The life-course perspective synthesizes both the developmental programming mechanisms of early life events and allostatic overload mechanisms of chronic life stress into a longitudinal model of health development. It is a way of looking at life not as disconnected stages but as an integrated continuum. Thus, to promote healthy pregnancy, preconception health must first be promoted. To promote preconception health, adolescent health must be promoted, and so forth. Rather than episodic care that many women receive, as a specialty we must strive toward disease prevention and health promotion over the continuum of a woman’s life course.

Principles of Practice Management

Principles of Practice Management

Patient Safety

Patient Safety