Talipes equinovarus

Introduction

This chapter provides a basic overview and is to be read in conjunction with the following reference sources:

1. Ponseti IV, Morcuende JA, Mosca V et al 2009 Clubfoot: Ponseti management, 3rd edn. Global HELP Organization publication (www.global-help.org). Available online as PDF file: http://www.global-help.org/publications/books/help_cfponseti.pdf (accessed 15 May 2009).

2. Evans AM, Do Van Thanh 2009 A review of the Ponseti method and development of an infant clubfoot program in Vietnam. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 99(4):306–316.

The presentation of a typical clubfoot in a newborn infant is often anticipated in developed countries where prenatal screening has detected and explored this developmental aberration. Treatment is expected and while the foot will not be perfect, the child will be carefully assessed and managed assiduously by physiotherapists and orthopaedists to ensure a good outcome. The child will be expected and able to play sports in most cases.

In a developing country, the neonatal clubfoot presentation can signal a bleak future of serious disability and potential poverty for the child and their family. Hindered mobility reduces education and employment prospects. Socially the child may grow into a marginalized and impoverished adult who will depend on family support or external aid sources to survive (Gupta et al 2006, Ponseti et al 2003, Tindall et al 2005). The frequent presence of many neglected adult clubfoot deformities in many of the developing countries reinforces this reality.

The clubfoot or talipes equinovarus deformity has long been recognized as a serious pediatric orthopaedic problem responsible for much suffering, multiple medical interventions and often disabling outcomes for the child (Ponseti et al 2003, Tindall et al 2005, Agrawal & Pandey 2007).

The incidence of infant clubfoot varies according to ethnicity (Pandey & Pandey 2003, Tachdjian 1985). The lowest incidence is found in Chinese infants (0.39 : 1000 births) and the highest incidence found in Polynesia (6.81 : 1000 births). The incidence among Caucasian infants is approximately 1.12 : 1000 births.

Surgical correction (once thought to be the optimal management approach) has now been replaced by non-operative correction as the almost universally accepted standard of initial treatment of congenital idiopathic clubfoot (Dobbs et al 2004, Morcuende et al 2004). While there are many methods of non-operative correction (manipulation and serial casting, physical therapy and continuous passive motion), which can be successful when correctly instituted, clinical reports have found success rates of only 15–50% (Dobbs et al 2004). The frequently reported exception is the Ponseti method which has reported impressive results in both the short and long term approximating greater than 90% (Changulani et al 2006, Herzenberg et al 2002, Morcuende et al 2004, Ponseti et al 2003).

The Ponseti method has gained increasing favour globally in the last three decades, although it has been used by the original author (Dr Ignacio Ponseti) since the 1940s. The follow-up results over 35 years are very good in terms of pain and function (Cooper & Dietz 1995). In contrast, the follow-up results for primary surgical correction involving extensive soft tissue release (the Turco procedure) are not good, with long-term results showing poorly functional, painful and arthritic feet (Dobbs et al 2006). The Ponseti technique has been refined over many years and current research continues to inform our practice and method (Dobbs et al 2004, Dyer & De Vaus 2006, Haft et al 2007, Herzenberg et al 2002, Lehman et al 2003, Pirani et al 2001, Shack & Eastwood 2007).

Basic pathology

The congenital idiopathic clubfoot deformity is identified by the presence of a retracted and inverted heel (equinus), usually a medial crease on the plantar aspect of the adducted forefoot and longitudinal arch cavus. Pathognomonic to this deformity is the inability to be able to bring the foot to a plantigrade position. In unilateral cases, the clubfoot is comparatively stiff, smaller with leg muscle atrophy and shortening also common.

In terms of aetiology, a normally developing foot deforms at approximately the 16th fetal week to become a clubfoot. While genetics and environmental influences are both probable contributors, it is curious to note that a more precise mechanism(s) of aetiology is still unknown. The primary deformity centres on the shape and position of the talus and the related misplacement of the navicular.

The Ponseti method focuses on stabilizing the talus and reducing the clubfoot deformity by abducting the inverted forefoot. This allows for the calcaneus to abduct, which, in turn, allows for the ankle to be dorsiflexed (often necessitating lengthening of the Achilles tendon) (Pandey & Pandey 2003; Ponseti 1997; Ponseti et al 2003, 2006).

Types

There are three main types of clubfoot to consider when diagnosing the infant clubfoot:

1. Congenital idiopathic clubfoot: a difficult deformity that affects otherwise healthy children.

2. Resistant clubfoot: often associated with syndromes such as arthrogryposis and stiffer in nature.

3. Atypical or complex clubfoot: a short, fat, stiff clubfoot which requires a very adapted casting approach (Ponseti et al 2006).

The Ponseti method

Key Concepts

The Ponseti method is not quick, but gives the best long-term results for the life of the growing child.

From the time of initial assessment and discussion with parents, the following process is followed:

1. Assess the clubfoot type.

2. Score the severity using the Pirani score (Fig. 8.1).

a. Assesses initial clubfoot severity.

b. Shown to be a reliable tool (Evans 2007).

c. Predicts the need for Achilles tenotomy (Shack & Eastwood 2007) and is prognostic (Dyer & De Vaus 2006).

e. The Pirani score is used at every cast change to monitor progress.

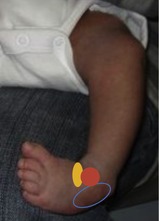

3. Manipulate to the correct position for the first cast (Fig. 8.2), repeated each 5–7 days (Morcuende et al 2005) until foot position is corrected, which usually takes approximately five to six casts (Fig. 8.3). Gentle manipulation of the foot first requires location of the head of talus (red) on the lateral side. The method of doing this is to: palpate the tibial and fibular malleoli with one hand, holding toes and metatarsals with the other hand. Slide thumb and forefinger from malleoli to the front of the ankle mortise. The navicular (orange) is small (forming) and, being medially displaced, will be found under the medial malleolus. The anterior calcaneus (blue) will be felt just below the talar head. Stabilize the head of the talus laterally so the foot can be abducted around the talus. Do not touch the calcaneus for this movement.

a. The arch cavus is corrected at the same time as reducing the forefoot adduction. This is achieved by inverting (supinating) and abducting the forefoot to align with the hindfoot (Morcuende et al 1994). The ankle equinus is corrected last (usually with a tenotomy).

b. To avoid upsetting or cutting the infant, cast saws are not used. Instead, it is recommended that all casts are soaked off 1 hour before the next cast is to be applied.

|

| Figure 8.2 |

4. Most cases require an Achilles tenotomy to gain full correction of the ankle equinus (Fig. 8.4).

a. The ends of the severed tendon have been found to appose again within 3 weeks (Barker & Lavy 2006).

b. Analytical radiography following the tenotomy procedure in clubfeet has demonstrated a reduction of the angle between the tibia and the calcaneus (i.e. the calcaneus is less retracted) and unchanged relationship between the tibia and the talus (i.e. prevented iatrogenic rocker-bottom foot) (de Gheldere & Docquier 2008).

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|