Breast-feeding

Breast-feeding is the best means of feeding babies, and all efforts should be made to promote, encourage and maintain it. Exclusive breast-feeding is recommended for the first 6 months of life. Breast-feeding can be continued for as long as mother and baby prefer (see Table 6.1).

Normal variations of breast-feeding

Frequency of feeds

Breast-fed infants usually feed every 2–5 h from both breasts each feed. Young babies feed frequently but demand feeding (i.e. feeding when hungry) will usually have the baby settle into a fairly predictable pattern of feeds. The frequency of feeds is determined by the baby’s appetite and gastric capacity, as well as the amount of mother’s milk available.

Length of feeds

The duration of the feed is determined by the rate of transfer of milk from the breast to the baby, which, in turn, depends on the baby’s suck and the mother’s ‘let down’. This may vary from 5 to 30 min. Young infants tend to feed for longer. It is the cessation of strong drawing sucks and the appearance of shorter-duration bursts of sucking that indicate the ‘end’ of the feed – not the time.

If the mother feels the baby is on the breast ‘all the time’, rather than focusing on the sucking alone, it is more important to look for longer duration of pauses between bursts of sucking. At this point, either take the baby off the breast or swap to the other side.

Appetite spurts

Babies seem to experience appetite spurts at 2 weeks, 6 weeks and 3 months. It is crucial that parents are aware of this or the baby’s natural increase in feed frequency may be mistaken for diminution of milk supply. This is especially true at 6 weeks when breasts are no longer carrying extra fluid and the supply is settling to the demands of the baby. Unfortunately, many women wean at this time through poor advice. Let the baby feed on demand, even 2 hourly, and this should settle in 48 h.

Table 6.1 How to assess good breast-feeding

Source: Murray S., Breast Feeding Information and Guidelines for Paediatric Units, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia 1992.

| Good | Problem | |

| Baby’s body position | On side – chest to chest | On back – angled away from mother |

| Mouth | Open wide | Lips close together |

| Chin | Touching or pressing into the breast | Space between chin and breast |

| Lips | Flanged out | Tucked in, inverted |

| Cheeks | Well rounded | Dimpled or sucked in |

| Nose | Free of or just touching the breast | Buried in breast, baby pulls back |

| Breast in mouth | Good mouthful, more of bottom part of breast in mouth | Central, little breast tissue in mouth or only nipple in mouth |

| Jaw movement | Rhythmic deep jaw movement | Jerky or irregular shallow movement |

| Sounds | Muffl ed sound of swallowing milk | No swallowing, clicking sounds> |

| Body language of the baby | Peaceful, concentrated | Restless, anxious |

| Body language of the mother | Comfortable, relaxed | Tense, hunched, awkward |

| Awareness of feelings during feed | Pain free, may feel a drawing feeling deep in breast or ‘let down’ | |

| Nipple, post-feed | Nipple elongated, well shaped | Not elongated, compressed ‘stripe’ or blanched |

Qualities of breast milk

Breast milk is naturally thinner in consistency than an artificial formula and may have a bluish tinge – this is normal, healthy and nutritious. The composition of breast milk varies during the feed. The fat content of milk varies diurnally: it is lowest at about 6 am and gradually increases to its peak at about 2 pm. At any one feed, the highest concentration of fat is at the end of the feed in the ‘hind milk’. The change in concentration is a gradual merging over the feed and is part of the feeding process. Hind milk is not ‘better’ than the early ‘fore milk’; fore milk is higher in water and lactose and provides liquid to quench the baby’s thirst and a quick surge of energy.

The presence of blood in the milk may cause a red or pinkish-brown discoloration. If this is present when the mother first starts expressing colostrum it may be due to duct hyperplasia. This gradually disappears and is of no significance. The most common cause of blood-stained milk (usually first noticed when the baby possets) is trauma to the nipple.

Bowel actions

The motions of breast-fed infants are normally bright yellow and soft to loose. The baby may have a bowel action with every feed (strong gastrocolic refl ex) or once every 5–8 days.

Mastitis is a common reason for early weaning. Any reports of pain by the mother should be actively addressed (see chapter 32, Neonatal conditions, p. 450).

Temporary cessation of breast-feeding

If the feeding pattern is interrupted because of illness, a planned fast for a procedure or the mother’s absence, the mother will need to express to maintain milk supply.

- Milk can be expressed by hand or by pump.

- Express as often as the baby would normally feed (i.e. 6–8 times a day). Several volumes of expressed milk can be added to the same bottle or storage bag (available from commercial pharmacies), but a new container should be used every 24 h.

- Milk may be kept in the freezer section of the refrigerator for 2 weeks or in the deep freeze for 3 months.

- To thaw frozen milk, place a bag/bottle in a container of cool water and run in hot water until the bag/bottle is standing in hot water. When the milk is thawed, it will be cold; continue to heat in hot water or place in the fridge until required for a feed.

- Thawed milk should be used within 24 h.

How much milk to express?

If the mother wants to express to give a feed by bottle or to substitute a feed as she is weaning, how much will the baby need?

Daily requirements of milk are:

- From 0–6 months: 150 mL/kg.

- >6 months: 120 mL/kg.

Growth in breast-fed infants

Growth patterns differ between breast-fed and artificially fed infants. Average weights of breast-fed babies are similar to or higher than formula-fed babies until 4–6 months, after which breast-fed babies slow significantly in their weight gain. Length and head circumference remain similar.

Growth charts are now available for fully breast-fed infants, although these are not in standard use. The naturally slower weight gain of breast-fed infants should not be taken in isolation as abnormal.

Maternal illness

When the mother is unwell, breast-feeding should continue. In the case of maternal infection, antibodies will pass through the breast milk to protect the baby.

Maternal drugs

If the mother has to take medication, the risk–benefit ratio should be weighed carefully by the prescriber. The mother should continue to breast-feed unless use of the drug is absolutely contraindicated during lactation and there is no safe alternative. There are very few such drugs and almost all have a safe alternative. If the mother is concerned about continuing breast-feeding, even if the drug is safe, suggest taking the drug after a feed to minimise the concentration or dividing the dose if possible.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D deficiency is increasingly recognised in Australia. Women who wear coverings (hejab), are dark-skinned or have limited sunlight exposure are at highest risk. They should be prescribed oral supplementation with vitamin D at 1000 IU/day during pregnancy. Their infants are at risk of vitamin D deficiency due to low hepatic stores and the paucity of vitamin D in breast milk. Exclusively breast-fed infants of vitamin D-deficient mothers should be screened or treated empirically e.g. with Penta-Vite 0.45 mL/day.

If breast milk is not available, either from the breast or as expressed milk, a commercially prepared formula should be chosen. These are based on cow’s milk, modified to lower the protein, calcium and electrolytes to levels better suited to the human infant and contain added amino acids, vitamins and trace minerals. See tables of formula composition at www.rchhandbook.org, Nutrition, chapter 6. A ‘from-birth’ formula should be selected for infants from birth to 6 months. For infants >6 months, follow-on formulas may be used. They have a higher protein and renal solute load and are not suitable for infants <6 months of age.

The introduction of some formula (e.g. when returning to work, low milk supply) need not mean the end of breast-feeding. A combination of breast and formula may be quite suitable for the infant.

Cow’s milk-based formulas

- The range of formula options has increased in recent years, with options now including specifically modified proteins, long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) and probiotics. All formulas meet the Australian Food Standards code and are suitable, although some are more expensive.

- Changes between types of formula are made for a variety of reasons, including irritability, poor sleep and possetting. In the normal thriving infant there is little indication to change the type of formula.

- Care should be taken when changing between formulas to use the correct scoop and dilution (as these vary between brands). A history for a formula-fed infant with possible feeding problems should include a review of formula preparation.

Soy formulas

If a soy-based feed is required, an infant formula should be chosen. These are nutritionally adequate for infants, but are suggested for specific indications (such as lactose intolerance) rather than as a regular feed option. Follow-on soy formulas are available.

Antiregurgitation formulas

Thickened formulas are aimed at reducing regurgitation. Their use should be limited to the stepwise treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux (see chapter 27, Gastrointestinal conditions page 345). They are not recommended in healthy infants without regurgitation.

Low-lactose formulas

Infant formulas with low-lactose content are recommended only in cases of proven lactose intolerance (see chapter 27, Gastrointestinal conditions page 340).

Hypoallergenic formulas

Based on partially hydrolysed protein in place of whole cow’s milk protein, this formula group is intended as part of a preventive programme for infants who are not being breast-fed and are at high risk of developing allergy. Breast-feeding continues to be the feed of choice in infants at high risk of developing allergy. Hypoallergenic formula is not to be used as a treatment formula for an infant with diagnosed cow’s milk allergy.

Babies <6 weeks of age usually feed every 3 h; however, they may take more each time and feed 4 hourly. Babies rarely sleep through the night before 6–8 weeks. When they miss a night feed (usually sleeping 5–6 h straight) they will have five feeds and consequently take more milk at each feed. Babies who sleep longer in the day (e.g. 5 h between feeds) often need to feed overnight to maintain adequate intake. Parents may need to wake the baby after 4 h in the daytime. There is no need to wake a baby overnight if intake and weight gain are adequate.

Introduction of whole cow’s milk

The introduction of cow’s milk products as part of an expanding diet is appropriate, but the main milk intake should be breast milk or formula until 12 months of age because of the risk of iron deficiency. Small amounts can be used on cereal, in custard and yoghurt from about 7–8 months.

Full-cream dairy products should be used for children up to 2 years; reduced-fat milk can be used from 2 years. Skim milk (essentially no fat) should not be used for children under 5 years.

Breast milk (or formula) will meet all nutrient needs until infants are 6 months old. This also corresponds to the age when most infants develop head control and oropharyngeal function sufficient to allow introduction of solids. From around 6 months solids can be introduced, to increase the intake of nutrients, such as iron, and as part of the educational process of learning to eat.

Solids can be iron-fortified baby cereal, smooth vegetables or fruits, followed by meat and chicken. Foods should be introduced one at a time to allow observation of tolerance. Texture should be increased so that by about 8–9 months the infant is managing lumps and varying textures, and is starting to manage finger foods.

By about 12 months, most family foods can be offered. Increasing intake of solids should result in a reduction of milk intake to about 600 mL/day by 12 months. Higher intake of cow’s milk limits the intake of other foods and is associated with iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency and associated anaemia is the most common nutrient deficiency in children in Australia. It is associated with the early introduction of cow’s milk, high intake of cow’s milk in the second year and low intake of iron-rich foods, such as meat and pulses.

There is no set rule for weaning time. Solids should be introduced at around 6 months and cup-drinking of breast milk, formula or water should start by 7–9 months. There is no need for the baby to be weaned to a bottle – if they are old enough they can go straight to a cup. Most babies can manage adequate fluid from a cup by 12–15 months.

Sudden cessation of breast-feeding leaves the mother at risk of developing mastitis. Ideally, weaning is achieved by reducing the feeds by one a week. Start by offering a drink in a cup or bottle instead of a breast-feed at midday, and gradually increase these other drinks. Many mothers retain the early morning feed or the last feed at night for longer.

Persistent difficulty in weaning usually requires someone to support the mother, giving the baby a feed and allowing the baby some time away from the mother to help with mutual separation. Both need to be ready to let go. Specialist lactation advice may be needed.

An assessment of the toddler who refuses food includes the following steps:

- Plotting weight and height to assure the parents of the child’s normal growth.

- Using the growth chart to demonstrate that the growth rate normally slows in the second year.

- Linking this to a lessened need for food and subsequent drop in appetite.

- Emphasising developmental progress.

Advise parents that:

- A healthy child will eat when hungry – quit the fight!

- Avoid arguments over food. Remember: ‘It’s the mother’s job to offer food, it’s the child’s job to eat it!’

- Showing independence is an important part of toddler development – choosing and refusing food is an expression of independence.

- Serve small portions – lower expectations.

- Include limited healthy options and allow the child to choose among the options.

- Include some healthy food choices that they like. Offering cereal at lunch is okay! A lack of variety is not a major worry at this age.

- Avoid filling up on milk and juice – large volumes of milk (>600 mL a day) can make the child feel full. Juice is not necessary in the child’s diet.

- Give the child time to enjoy the meal without comment. Remove the food after 30 min or if they dawdle or lose interest.

- Learning to eat is fun. Switch to finger food if they refuse to be fed.

- Do not use food as a punishment or reward. It only increases its potential power.

Daily food needs of preschoolers

The following is a guide to the quantities suitable for 2–5 year olds. Many parents are surprised at how little children of this age need. However, because total needs are small there is relatively little place for high-fat, high-sugar extras such as savoury snack foods and soft drinks.

- Milk group: 2 servings

– 1 serving = 250 mL of milk, 200 g of yoghurt or 35 g of cheese.

– Full-cream products are recommended up to 2 years; from 2 years reduced fat products can be included.

- Bread and cereal group: 4–5 servings

– 1 serving = 1 slice of bread, 1/2 cup of pasta or 2 cereal wheat biscuits.

- Vegetable and fruit group: 4 or more servings

– 1 serving = 1 piece of fruit or 2 tablespoons of vegetables − focus on variety of different vegetables and fruits rather than quantity.

- Meat or protein group: 2 servings

– 1 serving = 30 g of lean meat, fish or chicken, 1/2 cup of beans or 1 egg.

Feeding the sick infant and child

Nutritional assessment

A thorough nutritional assessment should be undertaken taking into account:

- Medical history:

– Type and duration of illness.

– Degree of metabolic stress.

– Treatment (medications or surgery, or both).

- Dietary assessment:

– 24 h dietary recall.

– 3 day food record.

- Physical examination:

– General assessment: wasting, oedema, lethargy and muscular strength.

– Specific micronutrient deficiencies: pallor, bruising, skin, hair, neurological and ophthalmological complications.

– Anthropometry – weight, length, head circumference – serial measurements plotted. Correct for age for preterm infants.

– Growth velocity.

– Skin fold thickness, mid-arm circumference.

- Fluid requirements:

– Take into account i.v. and enteral fluids.

– Any restrictions as per medical team.

- Laboratory data:

– Assessment of GI absorptive status – stool microscopy, pH and reducing sugars. – Protein status: albumin, total protein, pre-albumin, urea, 24 h urinary nitrogen.

– Fluid, electrolyte and acid–base status: serum electrolytes and acid–base, urinalysis. – Iron status: serum ferritin and full blood examination.

– Mineral status: calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, bone age and bone density.

– Vitamin status: vitamins A, C, B12, D, E/lipid ratio, folate and INR.

– Trace elements: zinc, selenium, copper, chromium and manganese.

– Lipid status: serum cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides.

– Glucose tolerance: serum glucose, HbA1c.

Establishing a nutrition treatment plan

Calculating nutritional requirements

Energy

Estimated energy requirements for the sick infant or child can be calculated by using either:

- The requirements of a normal well child of the same sex and age, or

- An estimate of basal requirements with additional stress and activity factors.

Less common, but the most accurate method to calculate energy requirements in very sick infants and children, is via measurement of energy expenditure using indirect calorimetry.

Energy requirements can be expressed as kilocalories (kcal) or as kilojoules. The conversion equation is: kJ = kcal × 4.2.

Recommended energy and protein requirements for healthy infants and children are based on nutrient reference values (NRVs) for use in Australia and New Zealand. A full statement of the NRVs can be found at www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/subjects/nutrition.htm

Energy requirements are increased in the following conditions:

- Very low birthweight (VLBW) infants.

- Chronic lung disease.

- Cardiac defects.

- Cystic fibrosis.

- Diseases causing malabsorption i.e. liver, SBS, allergic enteropathy.

- Burns.

- Tumours.

Energy requirements are decreased in:

- Critically ill patients who are ventilated.

Protein

Increased protein intake is recommended in:

- Protein-losing states i.e. enteropathy and nephrotic syndrome.

- Chronic malnutrition.

- Burns.

- Renal dialysis.

- HIV.

- Haemofiltration (∼2 g/kg per day).

Reduced protein intake is recommended in:

- Hepatic encephalopathy (0.3 g/kg per day).

- Severe renal dysfunction (not dialysed).

Fat

- Concentrated source of energy and essential for transport of fat-soluble vitamins and hormones.

- Deficiency can occur rapidly in neonates and is evidenced by reduced growth rate, poor hair growth, thrombocytopenia, susceptibility to infection and poor wound healing.

Micronutrients

Special consideration is needed when estimating the micronutrient requirements of sick children (see Table 6.2).

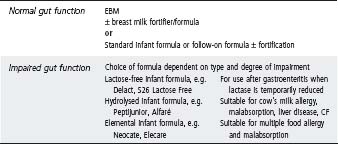

Feeds for infants

See Table 6.3.

- Breast milk, including expressed breast milk (EBM).

- Infant formulas, including ‘low birthweight’ formulas.

- Specialised feeds for specific disease states, e.g. inborn errors of metabolism, renal, complex malabsorption and liver conditions.

Breast milk

Breast-milk feeding should be the primary aim for very sick babies. When babies are too ill or too premature to suckle at the breast, most mothers can establish lactation by expression. EBM can be fed via a tube until the baby is well enough to be placed on the breast. In this way breast-milk feeding can be achieved in extremely premature babies and those with major malformations, birth defects and other serious illnesses. The only situations in which breast-milk feeding is not possible are:

- When an informed mother chooses not to express.

- Specific inborn errors of metabolism, which require exclusion formulas.

- Some complex malabsorption syndromes.

Table 6.2 Diseases that increase micronutrient requirements

| Disease | Increased requirement |

| Burns | Vitamins C, B complex, folate, zinc |

| HIV/AIDS | Zinc, selenium, iron |

| Renal failure: dialysis | Vitamins C, B complex, folate (reduce or omit copper, chromium, molybdenum) |

| Haemofiltration | Vitamins C, B complex, trace elements |

| Protein–energy malnutrition | Zinc, selenium, iron |

| Refeeding syndrome | Phosphate, magnesium, potassium |

| Short bowel syndrome, chronic malabsorption states | Vitamins A, B12, D, E, K, folate, zinc, magnesium, selenium |

| Liver disease | Vitamins A, B12, D, E, K, zinc, iron (reduce or omit manganese, copper) |

| High fistula output, chronic diarrhoea | Zinc, magnesium, selenium, folate, B complex, B12 |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | Vitamins A, D, E, K |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Folate, B12, zinc, iron |

Breast-milk fortifiers

Breast-milk fortifiers are available to add to EBM to increase its content of protein, energy and other nutrients. The addition of fortifier should be delayed until feeds are fully established (i.e. 150–200 mL/kg), unless babies have a condition requiring fluid restriction, e.g. congestive cardiac failure or chronic lung disease.

Babies who may benefit from fortifiers are those with increased nutritional requirements (e.g. VLBW babies) and those requiring fluid restriction (as listed above).

In addition, VLBW babies may require folate, iron, sodium and vitamins C, D and E. Iron should not be started until 12 weeks of age. VLBW babies who receive multiple blood transfusions may not need supplemental iron.

Infant formulas

When breast milk is not available an infant formula is required. Low birthweight (LBW) formulas are designed for very premature (<32 weeks) babies. In general, these contain more energy, protein, calcium, phosphorus, trace elements and certain vitamins than standard formula. They include LCPUFA as part of their fat content, based on evidence that this improves the developmental outcomes in premature infants. Generally LBW formulas are used until a weight of 2.5 kg is achieved. Babies are then fed with a standard infant formula which can be fortified if necessary.

Fortification of standard infant formulas

Standard formulas provide approximately 280 kJ/100 mL (20 kcal/30 mL) and 1.5 g protein/ 100 mL. Fortification should only be implemented under the supervision of a paediatrician or dietician.

- To increase energy to 350 kJ/100 mL (25 kcal/30 mL):

– Use additional formula powder, i.e. for formulas where the standard dilution is 1 scoop/30 mL of water, use 1 scoop/25 mL of water, or for formulas where the standard dilution is 1 scoop/60 mL of water use 1 scoop/50 mL of water.

– This will also increase protein and other nutrient intakes.

– Care should be taken in infants with renal or liver impairment.

- To increase energy to 420 kJ/100 mL (30 kcal/30 mL):

– Use additional formula powder as above with the addition of either glucose polymer or fat emulsion.

– Concentrate the formula further with additional powder (e.g. 1 scoop/30 mL to 1 scoop/20 mL). This provides an improved energy/protein ratio and additional nutrients which can be beneficial in fluid restricted infants and those with high catch up growth requirements. Use of this formula needs to be monitored carefully due to its higher renal solute load (RSL) and osmolality.

Specialised feeds can also be fortified in similar ways to the above.

- Infants and young children who develop an intercurrent gastroenteritis must have all fortification ceased until vomiting and diarrhoea resolve, to avoid the potential complication of hypernatraemic dehydration.

- VLBW babies require 180–200 mL/kg per day of EBM or standard formula, or 150– 180 mL/kg per day of fortified EBM or LBW formula, starting at 20–30 mL/kg per day at birth and increasing by 30 mL/kg per day as tolerated. Regimes should be modified according to condition and stability in VLBW infants. Initial feed frequency should be 1–2 hourly. Hourly feeds may be necessary in babies <1000 g.

- Orogastric tubes should be used in babies <1250 g, as nasogastric tubes cause significant airways obstruction. Continuous intragastric infusion of feed rather than intermittent boluses may help if reflux, gastric distension or apnoea is persistent.

- Term infants require 150 mL/kg per day. This is usually reached over 5–7 days, starting at 30–40 mL/kg per day and increasing by 30 mL/kg per day as tolerated. Feed frequency should be 3–4 hourly, although with reflux or abdominal distension, smaller volume and more frequent feeds may help.

Table 6.3 Appropriate feeds for infants

Table 6.4 Oral or enteral feeds for children 1–6 years (8–20 kg)

| Normal gut function | Concentrated infant formula |

| Standard paediatric formulas, e.g. | |

| Nutrini, Pediasure, Resource for Kids (added fibre also available) 4.2 kJ/mL (1 kcal/mL) | |

| Nutrini Energy, Pediasure Plus (added fibre also available) 6.3 kJ/mL (1.5 kcal/mL) | |

| Impaired gut function | Lactose-free formula, e.g Digestelact |

| Concentrated hydrolysed infant formula | |

| Hydrolysed formula, e.g. MCT Peptide 1+, Vital HN | |

| Elemental formula, e.g. Neocate Advance, Elecare, Paediatric Vivonex |

Feeds for children

Young children often maintain oral intake when they are ill. In some cases additional energy needs to be added to oral feeds to maintain nutritional status.

These include:

- Energy supplements, e.g. glucose polymers or fat emulsions added to normal foods and fluids to increase energy intake

- Complete supplements, e.g. Pediasure, Fortisip or Sustagen drinks, which can be used in addition to usual foods to increase energy, protein and nutrient intake.

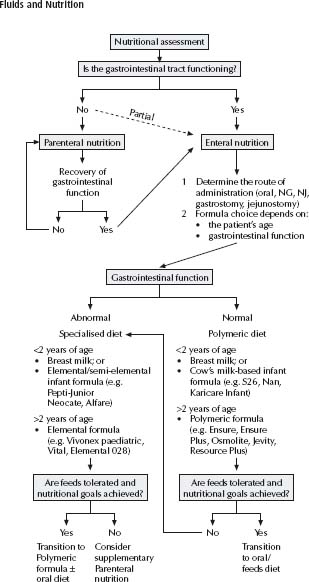

Enteral nutrition is the provision of nutrients to the alimentary tract through a feeding tube. It can be used to provide the total nutritional needs of a patient (either short or long term), or to provide additional nutrients when voluntary oral intake is inadequate. See nutritional support algorithm, fig. 6.1.

Enteral feeding has certain advantages over parenteral nutrition:

- Less risk of infection.

- Less risk of metabolic abnormalities.

- Nutrients provided to the alimentary tract enhance intestinal growth and function.

- Inexpensive.

Administration

The most commonly used route is nasogastric, its main benefit being ease of insertion. When long-term feeding is required, a gastrostomy tube may be indicated. It is generally placed endoscopically rather than surgically.

When gastric motility is poor or when gastric residues are persistently high, a nasojejunal tube may be of benefit.

Feeding method

When choosing a method consider the feeding route, the expected length of time the feed will be required and the type of feeding regime to be used (see Table 6.6). The introduction of hyperosmolar feeds should be gradual.

Selection of feed

A full nutritional assessment (current nutritional status, current intake, requirements and the consideration of medical condition/fluid restrictions) should be carried out by a paediatric dietician to establish which feed will be optimal. See Tables 6.4 and 6.5 for appropriate feeds to use with different age groups.

It is inappropriate to administer puréed foods down feeding tubes as the amount of fluid required to achieve a suitable consistency dilutes the energy and nutrient content, while increasing the risk of microbial contamination and tube blockage.

Monitoring enteral nutrition

When monitoring patients on enteral feeds, mechanical, metabolic, gastrointestinal, nutritional and growth parameters must be assessed routinely. In the early stages of feeding, the patient’s tolerance of the feeding regimen is critical to the success of feeding.

Once the feeding plan has been fully implemented, regular assessment of the patient’s nutrient requirements is needed to ensure that nutritional support has been adequately maintained and to indicate when enteral feeding can be possibly ceased.

From enteral to oral feeding

Once the patient is able and willing to eat by mouth, enteral feeds can be reduced in proportion to the amount consumed orally. Transition from continuous feeds to overnight feeds may help establish oral intake while ensuring the patient is not nutritionally compromised.

Table 6.5 Oral or enteral feeds for children 6 years+ (>20 kg)

| Normal gut function | Standard paediatric formula (as above) |

| Standard adult formula, e.g.: | |

| Osmolite, Nutrison Standard, Ensure, Jevity, Resource (added fibre available) 4.2 kJ/mL (1 kcal/mL) | |

| Ensure Plus, Nutrison Energy, Resource Plus, Fortisip (added fibre available) 6.3 kJ/mL (1.5 kcal/mL) | |

| Novosource 2.0, TwoCal HN 8.4 kJ/mL (2 kcal/mL) | |

| Impaired gut function | Hydrolysed formula, e.g. MCT Pepdite 1+, Vital Elemental formula, e.g. Elemental 028, Paediatric Vivonex, Vivonex TEN |

Table 6.6 Types of enteral feeding regimens

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Bolus feedings | Most closely mimics physiological feeding | Can be time-consuming for caregiver |

| Increases patient mobility | May decrease voluntary oral intake | |

| Little equipment is needed | ||

| Volume given can be precisely measured | ||

| Gravity drip | Little equipment needed | Rate of delivery cannot be closely monitored |

| Feeding most likely to be tolerated | ||

| Pump-assisted continuous | Feeding can be delivered while patient sleeps | Requires feeding pump |

| Larger volumes can be tolerated than if given by bolus method |

Home enteral feeding

The decision to provide home enteral feeding should take into consideration the patient’s medical needs and the practical, social and psychological factors that influence the family’s ability to cope with a home feeding programme.

Children on home enteral feeding, especially those who have minimal or no voluntary oral intake, require close monitoring of their growth and need their feeding regimens altered appropriately.

Common problems

- Gastrointestinal disturbance. This is the most common problem (diarrhoea, cramping, nausea and vomiting). It can be minimised by correct formula selection and review of medications. High gastric residues should be treated by reducing the rate of feeds given, feeding smaller volumes, continuously reassessing the concentration of feed and assessing GI function. Directing feed into the jejunum alleviates the problems caused by slow gastric emptying.

- Food aversion. Young children who have been fed enterally during infancy or for long periods of time may miss important developmental steps in self-feeding. Non-nutritive sucking and mouth contact or taking small amounts of appropriate food/fluid orally will help establish or maintain eating and feeding skills. A speech pathologist may be of assistance.

- Malnutrition is associated with major changes in electrolyte balance. Enteral feeding should be initiated with caution in patients with significant and long-standing undernutrition. Serum phosphate, potassium, magnesium and glucose levels should be assessed regularly (see Refeeding syndrome, p. 99).

General indications for parenteral nutrition:

- Recent weight loss of >10% of usual body weight and a non-functional GI tract.

- No oral intake for >3–5 days in a patient with suboptimal nutritional status and a nonfunctional GI tract.

- Anticipated need for parenteral nutrition for a minimum of 3–5 days.

Medical/surgical conditions that may require parenteral nutrition

- Patients unable to tolerate enteral feeding because of GI dysfunction; i.e. postoperative neonates, extensive short-bowel syndrome or severe malabsorption.

- Patients with increased metabolic requirements that may not be adequately treated with enteral therapy; i.e. severe burns, cystic fibrosis or renal failure.

For ordering and monitoring parenteral nutrition, refer to www.rchhandbook.org, Nutrition, chapter 6.

After a period of prolonged starvation, aggressive nutritional therapy may precipitate a cascade of potentially fatal metabolic complications. These include:

- Hypokalaemia.

- Hypophosphataemia.

- Hypomagnesaemia.

- Glucose intolerance.

- Cardiac failure.

- Seizures.

- Myocardial infarction/arrhythmias.

At particular risk are patients with:

- Anorexia nervosa.

- Classical marasmus.

- Kwashiorkor.

- No nutrition for 7–10 days in adolescents (much less in infants and children) with significant metabolic stress.

- Acute weight loss of ≥10–20% of usual body weight and possibly metabolic stress, or >20% of usual body weight.

- Morbid obesity with massive weight loss (i.e. postoperative).

Management

- Identify risk and chronicity.

- Identify and treat metabolic stress if present (e.g. infection).

- Establish baseline status: weight, height/length, head circumference, fluid status, electrolytes, urea, creatinine, calcium, phosphate and magnesium, prior to commencing nutritional rehabilitation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree