CHAPTER 6 Menopause

The word menopause comes from the words meno (monthly menses) and pausis (pause), meaning a pause in menstruation, or, more correctly, the cessation of menstrual cycles. Menopause is a natural and normal part of aging, except when brought about through surgery or as the result of medication or illness. The average age of menopause is 52 years, and it commonly occurs between the ages of 42 and 56 years. The signs and symptoms generally ascribed to menopause include hot flashes, mood swings, depression, vaginal dryness, sleep disturbances, heart palpitations, headaches, urinary tract infections, and decreased libido. As women lose the support of estrogen, they are at increased risk for developing osteoporosis and heart disease. Some women pass through menopause with few physical or emotional complaints, whereas others become debilitated by the physical and emotional manifestations of the “change.” By the year 2015, nearly 50% of American women will be in menopause.

MENOPAUSAL SYMPTOMS AND THERAPIES

The primary symptoms of menopause for many women are hot flashes and night sweats. However, a great deal of variation exists among individual women and cultures. Approximately 70% of American women have at least one hot flash during their menopausal years, Greek women report a higher rate of hot flashes, Japanese women report fewer hot flashes, and Mayan women report no symptoms at all. A number of cultures do not even have a word for hot flash even though all women go through menopause. Variance in symptoms could be the result of diet, lifestyle, environment, or societal perception.

Hormone Therapy

HRT has been successfully used for decades to treat the symptoms of menopause. Minor side effects associated with HRT include bloating, breast tenderness, cramping, irritability, depression, breakthrough bleeding, or a return of monthly periods. Many women find these side effects unpleasant, and even before the release of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) findings that put the safety of HRT in doubt, approximately two in three women who started either estrogen replacement therapy or HRT discontinued therapy within a year, regardless of hysterectomy status.1 But these minor side effects did not compare to the concerns for more severe adverse events that were generated with the release of the findings of the WHI in July 2002.

The WHI is a large-scale, randomized, controlled clinical trial of 16,608 menopausal women aged 50 to 79 years with an intact uterus at the time of enrollment who were randomly assigned to receive either HRT in the form of 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogens and 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Prempro) or placebo. The study was halted after 5.2 years on the recommendation of an independent review board because of an unacceptably higher risk of breast cancer in women receiving HRT.2 When compared with those receiving placebo, women assigned to the combination HRT group also had more strokes, heart attacks, and blood clots. Although the HRT users also had a reduced risk of colorectal cancer and fractures (including hip fractures), overall the observed risks outweighed these benefits.3 Patients and practitioners then waited for the results of the estrogen-only arm of the WHI, which was to finish in 2005. However, on March 1, 2004, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) informed study participants that they should stop study medications in the trial of conjugated equine estrogens (Premarin, Estrogen-alone) versus placebo in the WHI. Participant follow-up will continue for several more years, including ascertainment of outcomes and mammogram reports. Almost 11,000 women with a prior hysterectomy aged 50-79 at baseline participated in the WHI estrogen-alone trial, which was designed to determine whether estrogen prevents heart disease in healthy older women. Hip fractures were the major secondary outcome, and breast cancer the major possible risk. When the study was stopped by the NIH, women, who now have an average age of almost 70 years and have been followed for approximately 7 years, were told that the current results show that estrogen alone does not appear to affect (either decrease or increase) coronary heart disease and appears to increase the risk of stroke. Other findings included a decreased risk of hip fracture and no increase in the risk of breast cancer during the time period of this study.4

The WHI Memory Study (WHIMS), an ancillary study of the WHI, found that estrogen plus progestin did not improve cognitive function when compared with placebo in postmenopausal women aged 65 years or older. This study also found a small increased risk of clinically meaningful cognitive decline in the estrogen plus progestin group.5 On the basis of these collective findings, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended against the routine use of HRT for the prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women.6

Women and health care providers are understandably concerned with the results from the WHI study. Statistics can be confusing to interpret, and practitioners should clarify the difference between relative and absolute risks when talking to women about the results of the WHI, which include the following:

A 26% increase in breast cancer risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 8 more women would develop breast cancer when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT.

A 26% increase in breast cancer risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 8 more women would develop breast cancer when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT. A 29% increase in heart attack risk means if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 7 more women would have a heart attack when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT.

A 29% increase in heart attack risk means if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 7 more women would have a heart attack when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT. A 41% increase in stroke risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 8 more women would have a stroke when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT.

A 41% increase in stroke risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 8 more women would have a stroke when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT. A 37% decrease in colorectal cancer risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 6 fewer cases of colorectal cancer would be seen in this group when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT.

A 37% decrease in colorectal cancer risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 6 fewer cases of colorectal cancer would be seen in this group when compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT. A 34% decrease in hip fracture risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 5 fewer hip fractures would be seen in this group compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT.

A 34% decrease in hip fracture risk means that if 10,000 women were taking HRT for 1 year, 5 fewer hip fractures would be seen in this group compared with 10,000 women not taking HRT.For many American women, one of the major concerns of the study was the increased risk of breast cancer. The WHI found that relatively short-term combined estrogen plus progestin use increases incident breast cancers, which are diagnosed at a more advanced stage, compared with placebo and also substantially increases the percentage of women with abnormal mammograms.7 However, it must be asked whether the addition of progestin to estrogen increased the risk of breast cancer in this trial population, especially since the estrogen-only arm, at least at the time of this writing, did not appear to be associated with increased risk. Although the data on progestin and breast cancer risk are limited, some observational studies do suggest a relation. In a cohort of 46,355 postmenopausal women, after 4 years of use, combined estrogen and progestin therapy was associated with a higher incidence of breast cancer than therapy with estrogen alone (relative risk, 1.4 and 1.2, respectively; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-1.8 and 1.0-1.4, respectively).8 The relative risk increased by 8% (95% CI, 2%-16%) per year of use of estrogen plus progestin compared with 1% (95% CI, 2%-3%) per year of estrogen use alone. This finding is consistent with a recent report from Sweden that found longer use of HRT containing progestins significantly elevated breast carcinoma risk, whereas estradiol use alone did not. Continued use of progestins rendered the highest risks.9 Other questions that remain to be answered include whether natural progesterone is safer than progestin, and whether it is safer to administer progestin every 3 months to induce withdrawal bleeding than to use it cyclically every month or continuously.

Prempro is only one of many formulations of hormone therapy available in the marketplace. This must be considered when confronted with the WHI report of increased risk of adverse events. Premarin is a mixture of sodium estrone sulfate and sodium equilin sulfate.10 Equilin occurs naturally in horses but is not found in human beings. A number of researchers and health care practitioners question what the results would have been if a low-dose 17β-estradiol had been used. Or what about the use of a transdermal estrogen that is less likely to stimulate the production of oncogenic metabolites? While researchers and practitioners speculate, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has stated that though combinations of other estrogens and progestins were not studied in the WHI, in the absence of comparable data, the risks should be assumed to be similar. More research is obviously needed before definitive answers are available.

Individually Compounded Hormone Replacement Therapy

A growing trend among complementary medicine practitioners is the use of individually compounded HRT (ICHRT) containing “natural” or “bioidentical” hormones made from soy or yams. Proponents of this type of therapy claim that hormones that are bioidentical to those produced by the human body are safer than other forms, such as conjugated equine estrogen. Jonathan Wright, MD, a strong proponent of using ICHRT, has proposed that hormone replacement should mimic the ratios of estrogen that naturally occur in a woman’s body, which he purports to be 90% estriol, 3% estrone, and 7% estradiol.11

Based on this ratio, a popular preparation of ICHRT is Tri-Est 2.5 mg, or triple-estrogen therapy. This blend of estriol (1 mg), estrone (0.125 mg), and estradiol (0.125 mg) is taken twice a day. Tri-Est 2.5 mg is said to be roughly equal to 0.625 mg Premarin.12 Bi-Est is another popular compounded blend composed of estriol (80%) and estradiol (20%).

Complementary practitioners often claim that higher estriol levels protect against the more potent effects of estrone and estradiol, making the development of estrogen-driven cancers less likely. Diet and environment may play a role in the relative amounts of these hormones in a woman’s body. Premenopausal Asian women have a lower breast cancer risk than white women and have a higher rate of urinary estriol excretion. When Asian women migrate to the United States, urinary excretion of estriol decreases and the risk for breast cancer increases.13 Estriol has been shown to protect rats against breast cancer induced by various chemical carcinogens.14 Estriol may prove to have a protective effect against the development of breast cancer, but it is premature to make this claim.

Estriol is sometimes prescribed without progesterone because some proponents claim that it does not stimulate endometrial proliferation. However, a population-based, case-control study in Sweden found that 5 years of oral use of estriol, 1 to 2 mg/day, increased the relative risk of endometrial cancer compared with women who had never used estriol. The odds ratio was 8.3 for atypical endometrial hyperplasia and 3.0 for endometrial cancer.15 Women using estriol, or a compounded formulation, should be instructed to use progesterone either cyclically or every 3 months to protect the endometrium.

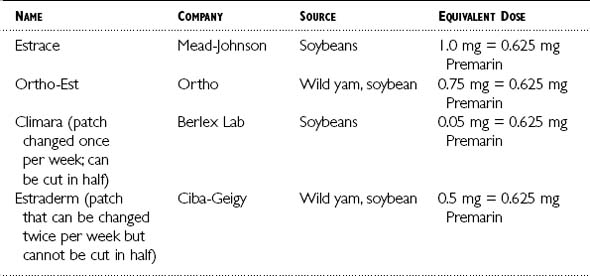

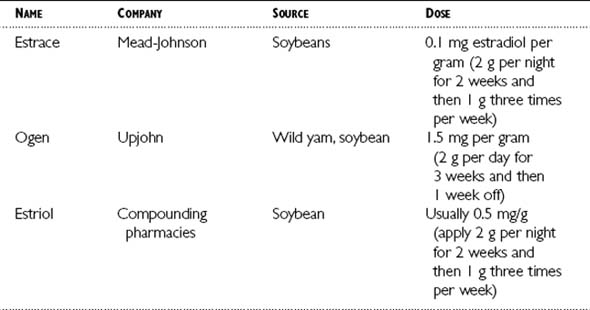

Table 6-1 lists a few estrogen replacement compounds containing estradiol derived from natural sources that can be taken orally or as a transdermal patch. Table 6-2 lists a few examples of estrogen creams derived from natural sources.

The route of administration should be based on the patient’s history, risks, and personal preferences. When estrogen is given orally, it must pass through the liver, where it is converted to a less active form of estrogen before it reaches the bloodstream. When the hormone is given in the form of a patch, it is directly absorbed into the bloodstream before it passes through the liver. Oral estrogens elevate C-reactive protein16 and triglycerides, whereas the patch does not.17

Options for Progesterone Replacement

Women who have a uterus must take a progestational agent if they are using estrogen replacement therapy to prevent endometrial cancer. For the past 20 years, the most commonly prescribed progestin in the United States has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA).18 Oral progesterone administration has always been problematic because of poor absorption and short biologic half-life. Natural progesterone in powder form is destroyed by stomach acid. This has been overcome by decreasing the size of progesterone particles through the process of “micronization”19 followed by dissolution in oils consisting primarily of long-chain fatty acids. Micronized progesterone (MP) is identical in chemical structure to endogenous progesterone and manufactured from the wild yam or soybean precursor diosgenin.20 It is available as Prometrium or through compounding pharmacists as oral MP. Side effects include bloating, breast tenderness, and drowsiness. Drowsiness can be minimized by taking it before bed. Bloating and breast tenderness are dose related. The Food and Drug Administration recognizes a dose of 200 mg for 12 sequential days per 28-day cycle for prevention of endometrial hyperplasia in women who are taking estrogen replacement therapy. Now that a bioavailable form of natural progesterone has entered the U.S. marketplace, the question arises of which progestogen to use.

All treatment groups had higher HDL levels (CEE only and CEE plus MP regimens more than CEE plus MPA regimens), lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, and higher triglyceride levels compared with the placebo group. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings increased over time in all groups, including the placebo group. Fibrinogen levels increased in the placebo group but remained at baseline in all treatment groups. Glucose levels were higher in all treatment groups. The placebo group had the most weight gain, whereas the CEE-only group had the least.21 The authors concluded “in women with a uterus, CEE with cyclic MP has the most favorable effect on HDL-C and no excess risk of endometrial hyperplasia.”

A 1985 Swedish study included 58 postmenopausal women who received 2 mg oral estradiol daily for 3 months followed by an additional 3-month course of 2 mg of estradiol daily plus 10 mg of MPA, 200 mg of MP, or 20 μg of levonorgestrel given for 20 days of each menstrual cycle. There was a significant decrease in HDL cholesterol in the groups receiving estradiol plus MPA or levonorgestrel. No change in HDL cholesterol was noted in the group receiving estradiol with MP.22 Two other small trials by Hargrove et al.23 and Jensen et al.24 have shown similar results.

However, a 1998 study of 123 postmenopausal Asian women receiving CEE alone, CEE plus MPA, or CEE plus MP did not show the same favorable effect on lipids. At the end of the 6-month trial, the groups receiving CEE alone and CEE plus MPA had a significant decrease in LDL levels that was not observed in the CEE plus MP group. An increase in HDL cholesterol was only noted in the group receiving CEE alone. A confounding factor in this study could be diet because many Asian diets are rich in phytoestrogens. Japanese women consuming a traditional diet were found to have 100 to 1000 times higher levels of urinary phytoestrogens than American and Finnish women eating an omnivorous diet.25 Because diets high in phytoestrogens have a favorable effect on cholesterol, there may have been little room for improvement in the lipid profiles of the Asian women in this study.

No comparative trials had been conducted between MPA and MP for their effects on bone density. When MPA is given alone, no beneficial effect results on bone density in postmenopausal women. When combined with estrogen therapy, studies demonstrate a neutral26 or additional beneficial effect27 on bone density. A Danish study found that MP did not affect the bone-preserving effects of estrogen.28 Although some authors suggest that MP is safer,29 there are no comparative studies addressing the question of breast cancer risk and the use of MP versus MPA.

Wild Yam and Progesterone Creams

Wild yam (Dioscorea villosa) has been promoted as an herb that, when either taken internally or applied topically, can be converted in vivo into progesterone. Despite such claims, wild yam is not converted to progesterone in the body, and a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study failed to show any statistical difference between a topically applied cream containing wild yam extract and placebo in alleviating menopausal symptoms or altering serum and salivary hormone levels.30 Although these products are prevalent in the marketplace and claim to “balance” women’s hormones, no historic or contemporary evidence validates this use.

John Lee, MD, has been a major force behind the use of progesterone cream for menopausal symptoms and for the treatment of osteoporosis. Lee describes an unselected case series of 100 postmenopausal women (aged 38 to 83 years) who received a 3% progesterone cream that was applied 12 consecutive nights per month or during the last 2 weeks of estrogen use. Total dose was one half to one third of an ounce of cream per month. The cream was applied to the neck, face, or under the arms, rotating sites. Women were given strict dietary instructions that included increasing green vegetables, avoiding all carbonated sodas, limiting alcohol intake, and reducing red meat consumption to three or fewer times per week. The following were also given: 400 IU of vitamin D, 2000 mg of vitamin C, 25,000 IU of beta carotene, and calcium, 800 to 1000 mg/day. Conjugated estrogens (0.3 or 0.625 mg/day) were taken 3 weeks per month unless contraindicated. Women were prescribed exercise for 20 minutes per day or 30 minutes three times per week. Serial bone densities were performed at 6- to 12-month intervals. Sixty-three of the 100 women underwent dual-photon absorptiometry. The author reported an overall increase of more than 15% in bone mineral density (BMD) over a 3-year period. The development of endometrial carcinoma in one 74-year-old woman is concerning and not surprising, given that estrogen was administered without an oral progestational agent.31

In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 102 healthy menopausal women who had not taken HRT for 1 year, a cream containing 20 mg/dose of progesterone or a placebo was applied once daily for 12 months. All women were given a multivitamin and 1200 mg of calcium daily and were evaluated for symptoms every 4 months for a 1-year period. Evaluation of BMD by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and lipid profiles were done at baseline and repeated after 12 months. The study found no significant difference between the progesterone and placebo groups regarding BMD of the spine and hip or lipids; however, women in the progesterone group showed a reduction in the frequency of hot flashes. Among women with vasomotor symptoms at the onset of the study, 25 of 30 in the topical progesterone group reported an improvement compared with 5 of 26 in the control group.32

However, other researchers have failed to note any beneficial effect of progesterone cream on menopausal symptoms. A parallel, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing the effect of a transdermal cream containing a progesterone (32 mg daily) with a placebo cream in 80 postmenopausal women failed to note any detectable change in vasomotor symptoms, mood characteristics, sexual feelings, blood lipid levels, or bone metabolic markers despite a slight elevation of blood progesterone levels.33

On the basis of evidence to date, topical progesterone cream should not be relied on to maintain bone density or protect the uterine endometrium from exogenous estrogen. It is concerning that some practitioners are prescribing oral estrogen and using topical progesterone creams to protect the endometrium. A crossover study enrolled 20 surgically menopausal women not receiving HRT who were randomly assigned to apply 1 tsp of Progest cream or placebo cream two times daily for 10 days, followed by a 4-day washout before participants switched creams. Participants were then given oral MP (100 mg every morning and 200 every evening) for 5 days. Plasma progesterone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP), and pregnanediol-3α-glucuronide (P3G) levels were used for evaluation purposes. Median plasma levels were 2.9 nmol/L after 10 days of Progest cream compared with 9.5 nmol/L after oral progesterone. Urine P3G levels were 4.2 μmol after Progest administration and 291 μmol with oral progesterone. Serum levels of 17-OHP were similar for Progest cream (1.1) and oral progesterone (1.2). The authors stated that 3 nmol/L is not enough to protect the endometrium from estrogen stimulation.34

These findings are consistent with a recent study of 27 women who were given a combined regimen of transdermal estrogen on a continuous basis throughout the 28 days of an average menstrual cycle in addition to sequential use of a cream containing 16, 32, or 64 mg of progesterone on a daily basis from days 15 to 28 of the cycle for three cycles. The study failed to show any secretory change in the subjects’ proliferative endometrium.35 Levels of salivary progesterone in the study were so variable as to be considered completely unreliable in determining the potential influence of the regimen on biologic progesterone activity. This finding is in accord with other research questioning the value of salivary progesterone testing.36

HERBS AND OTHER THERAPIES

Black Cohosh Root (Cimicifuga racemosa)

Cohosh is an Algonquian word meaning “rough,” in reference to the root. Black cohosh is an indigenous herb that was used by Native Americans to treat musculoskeletal pain, aid in childbirth, and treat respiratory complaints (Figure 6-1). A popular remedy among physicians and the general public, use of the root spread to England where it was used as a treatment for rheumatic symptoms and chorea. Black cohosh was also used for the treatment of depression during the nineteenth century.37 The sedative effects of the herb were not overlooked by the physicians of the day. The American Medical Association stated in 1849 that they “uniformly found Cimicifuga to lessen the frequency and force of the pulse, to soothe pain and allay irritability.”38 A survey of physicians in 1912 found that at the time it was one of the most popularly prescribed herbs in the United States.39 Black cohosh was referred to as black snakeroot (Cimicifuga, black cohosh, black snakeroot, and Macrotys) in the United States Pharmacopoeia from 1820 until 1890, when it was referred to as Black cohosh remained an official drug until 1926. A very popular female remedy of the nineteenth century was Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, of which black cohosh was a prominent component. This remedy can still be found, but it no longer contains black cohosh.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree