Assessment of acute pain

Pain scores are important! They are the fi fth vital sign on patients’ observation charts. Pain assessment includes a combination of the following:

History

- Including site, onset, duration, quality, radiation, triggers and relievers, impact on functioning (including sleep disturbance and other activities), treatments tried and their effectiveness.

- In developmentally normal children, ask the child directly about their pain using appropriate tools.

- In neonates, pre-verbal children and cognitively impaired children, parents and regular caregivers are often best equipped to interpret the child’s pain reliably.

Examination

- Behavioural observation (e.g. vocalisation, facial grimacing, posturing, movement).

- Physiological parameters (e.g. heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure) and physical signs (e.g. muscle spasm).

- Functional effects: for example, the ability to move (e.g. sitting up after laparotomy) and the tolerance of touch of the painful area usually signify adequate analgesia, whereas a child lying still and withdrawn may be in severe pain.

Use of pain-rating scales

Observe trends of change in an individual’s pain score or function (e.g. ability to turn in bed comfortably, ability to walk to the toilet) rather than the ‘raw’ pain score.

- Verbal children:

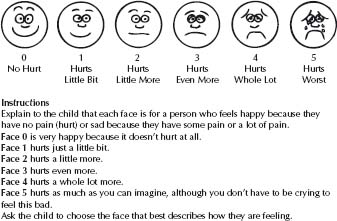

– FACES scales for children >4 years, e.g. Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (Fig. 4.1) or Bieri revised.

– Visual analogue scale (e.g. 100 mm ruler).

– Verbal numerical rating scale (e.g. ‘out of 10 …’).

- Non-verbal children including neonates and cognitively impaired are particularly vulner able (see Pain in children and adolescents with disabilities, p. 70).

– FLACC: Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability.

– PATS (for neonates): Pain Assessment Tool Score.

Multimodal analgesia (MMA) involves the use of more than one drug and/or method of controlling pain to obtain additive benefi cial effects, reduce side effects, or both.

MMA use is ideal for acute pain management including pain due to surgery, trauma or cancer, as it allows analgesia to be optimised and directed according to the multiple sources of pain (somatic, visceral and/or neuropathic).

Fig. 4.1 Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale. (Reproduced with permission from Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML: Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, ed. 7, St. Louis, 2005, p. 1259. © Mosby.)

Drug options include paracetamol, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, muscle relaxants (e.g. buscopan for smooth and diazepam for skeletal muscle spasm), tramadol and neuropathic analgesics (such as gabapentin, amitriptyline, clonidine and ketamine).

Drugs can be administered by various routes. Specialised infusions (e.g. local anaesthetics, ketamine and opioids) can be via bolus and/or continuous infusion.

Use an analgesic ladder approach to manage acute pain (see Table 4.1). The progress up or down the steps varies according to:

- the intensity of pain experienced

- its anticipated duration

- the expected recovery period.

Each step up employs all the analgesics listed in the steps below. Once pain is controlled, wean back to the previous step. This varies with the speed of resolution of the painful condition and the number of breakthrough or rescue agents that are required in the higher category. If pain is poorly responsive to these measures, get consultant assistance.

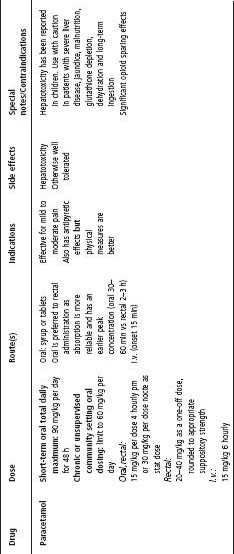

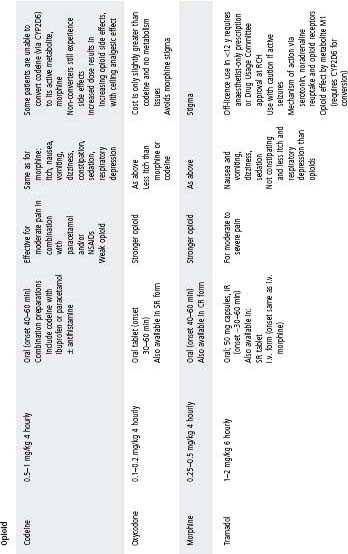

See Table 4.2 for dosing.

Examples of patients with severe pain and suggested management

Femoral fracture

- Single shot local anaesthetic femoral nerve block.

- Diazepam.

- Place in back slab or traction.

- Give other agents according to need.

Table 4.1 Analgesic ladder approach

| Degree of pain and setting | Analgesic ‘steps’ |

| Severe pain inpatient | Add specialised infusion, e.g. ketamine, epidural local anaesthetic |

| Add parenteral opioid by infusion (nurse or patient controlled) | |

| outpatient or emergency presentation | Add parenteral opioid by bolus or regular oral opioid (consider controlled release when long duration) |

| Consider parenteral tramadol, NSAID, paracetamol | |

| Address sleep impairment and anxiety if present | |

| Moderate pain | Add one (or combination) of: strong opioid e.g. oral morphine, oxycodone ‘non-opioid’: tramadol mild opioid: codeine |

| Address environmental/psychosocial contributors | |

| Mild pain | Begin with paracetamol and/or NSAIDs |

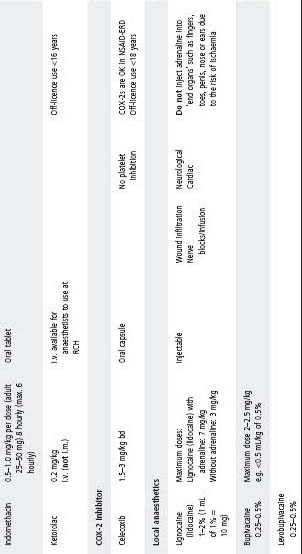

Table 4.2 Analgesic medication

COX, cyclooxygenase; CR, controlled release; ERD, exacerbated respiratory disease; IR, immediate release; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-infl ammatory drugs; SR, slow release.

Bowel obstruction requiring large laparotomy

The patient will be nil orally and will universally require parenteral analgesia for severe pain. The following are suggested options. It is important that analgesia be commenced even if the child is to be transferred to a larger centre.

- Regular parenteral NSAID and paracetamol and

- Postoperative epidural local anaesthetic infusion; or

- Opioid via patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and ketamine infusion.

Metastatic cancer with bony metastases and large intraabdominal mass

- Will benefi t from regular dosing with a long acting opioid such as MSContin or fentanyl patch (applied every 3 days).

- Manage breakthrough pain with immediate release morphine, fentanyl lozenges, sufentanil nasal/buccal spray or ketamine lozenges.

- See also Haematology and Oncology, chapter 29, p. 377.

See Procedures, chapter 3.

Everyday events such as blood collection, cannula insertion, port cannulation, lumbar puncture and suturing are often a source of fear and anxiety for children. The aims of treating procedure-related pain are to prevent or minimize pain and distress.

Children with illnesses that require multiple painful procedures should be treated with care and sensitivity from the outset to avoid unnecessary psychological trauma. Anticipation by staff and preparation of patients and their parents are of key importance. Consider:

- The patient: age, previous experiences, emotional and physical condition of the child.

- The procedure: is it needed and how urgently, the level of expected pain and duration.

- The proceduralist: availability of appropriately skilled staff.

Always combine pharmacological and non-pharmacological techniques.

- Behavioural strategies (e.g. calico dolls, play therapy) can be used before all painful procedures.

- Analgesic and sedative drugs are added when required.

- Remember that sedatives alone are not analgesics.

- It is diffi cult to assess pain and the effects of analgesia and sedation in neonates and children with cognitive impairments.

Before the procedure

General principles – preparation is the key

- Prepare yourself and the other staff involved.

- Ensure parents and the child understand what the procedure involves. Ideally, prepare the child <6 years immediately before the procedure and >6 years 1 week before.

- Avoid medical jargon; explain what is going to happen and in what order.

- Obtain consent from the parents (verbal or written as required).

- Set up your equipment before the child enters the procedure room.

- Encourage the parents to play an active role during the procedure by involving them in distraction techniques and comfort strategies. Avoid asking them to restrain their child.

- Children may be assisted to develop their own personal procedure routine, comfort or distraction strategies, e.g. counting backwards from 100.

- An explanatory video may be helpful in preparing the child and their parent for the procedure.

- If considering sedation, ensure adequate staffi ng and resources are available.

Pharmacological

- Topical anaesthetics (e.g. AnGel, EMLA for intact skin; Laceraine for wounds).

- Oral paracetamol, and/or NSAIDs and/or opioids e.g. oxycodone.

During the procedure

General principles

- Give the child some feeling of control (choice of hand for i.v., sitting up or lying down).

- Prompt the child to use the previously planned coping methods.

- Monitor the pain and effectiveness of pain management techniques during a procedure.

- If the child is not coping well, consider changing pain control measures or aborting the procedure.

- Consider sedation, depending on the procedure involved and the child’s previous experience.

Comfort techniques

- Position for comfort (i.e. infants on parents’ lap with physical/eye contact with parent).

- Have parents comfort child with gentle massage/touch or holding hands.

- Calm breathing.

- Swaddling for infants (<6 months).

Distraction techniques

- Choosing and playing a music CD or watching a favourite DVD.

- Playing with developmentally appropriate toys.

- Counting objects in the room or looking at posters on the wall or ceiling.

- Reading interactive storybooks.

- Visual imagery (e.g. ask the child to imagine a place where they would like to be and to tell you about it).

Pharmacological techniques

- Sucrose: for infants (2 mL of 33% sucrose). Give 0.25 mL 2 min before the start of a procedure onto the infant’s tongue. Offer a dummy if it is part of the infant’s care. Give the remainder of the sucrose slowly during the procedure.

- Topical local anaesthetic (e.g. EMLA or AnGel).

– i.v. cannulation, lumbar punctures and blood sampling are all potentially distressing for children.

– Apply local anaesthetic cream 60–90 min before soft tissue needling procedures (this ensures skin analgesia a few millimetres deep).

– Creams remain effective for up to 4 h after application.

– EMLA is a mixture of prilocaine 2.5% and lignocaine (lidocaine) 2.5%, and often vasoconstricts the area under application (onset 60–90 min).

– AnGel (amethocaine 1%) has a faster onset than EMLA (60 min). If amethocaine is left on for >1 h, erythema and itch can occur.

- Peripheral nerve block.

- I.v. regional anaesthesia (e.g. Bier’s block).

- Local anaesthetic infi ltration (lignocaine [lidocaine], ropivacaine, bupivacaine or levobupivacaine).

– The skin and subcutaneous tissues can be effectively infi ltrated with local anaesthetic solutions.

– Lignocaine (lidocaine) stings as it is injected. Stinging may be reduced by adding 1 mL 8.4% sodium bicarbonate to 9 mL of lignocaine (lidocaine) solution.

– The addition of adrenaline 1 : 200 000 or 1 : 400 000 (or 5–10 mcg/mL) may increase the duration of action, slows systemic absorption by up to 50% and reduces bleeding, but adrenaline should not be used in ‘end organs’ such as fi ngers, toes, penis, nose or ears because of the risk of ischaemia.

- Nitrous oxide.

– Useful inhalational analgesic agent which provides potent short-term analgesia for painful procedures such as wound dressings and the removal of catheters.

– Rapid onset and offset.

– Side effects may include sedation, nausea and vomiting. Bone marrow depression can occur with prolonged exposure (>12 h) – consider in the child requiring daily repeat procedures.

– Do not use in patients with head injuries, pneumothorax, cardiac disease and those who are obtunded.

– The person administering nitrous oxide should have adequate airway management skills.

– Fast patient before administration (2 h for solids and liquids, or longer as clinically appropriate for more complex patients).

– Methods of delivery include:

Entonox (a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen).

Quantifl ex (variable demand delivery system of nitrous oxide and oxygen).

- Intranasal fentanyl

- Has been used in Australian emergency departments in the initial pain management of long-bone fractures.

- A more concentrated solution of 300 mcg/mL was initially used, administered via an atomiser at a dose of 1.5 mcg/kg, given into one nostril only (where the child is >50 kg or if the less concentrated solution is used, give half the dose into each nostril).

- This has been administered prior to cannulation for subsequent opioid analgesia to be given intravenously.

- Note: the role of this agent via this route as the neat standardly available solution (100 mcg/2 mL) in procedural sedation requires further delineation.

Anxiolytics and sedatives

Procedural sedation should only be undertaken by accredited staff members, with appropriate monitoring and equipment and line-of-sight nursing until return to baseline sedation score. Midazolam oral 0.5 mg/kg (usual max. 15 mg) 20–30 min before treatment. Intranasal delivery stings and is now avoided at RCH.

- Sedation is not analgesia!

- Sedation alone is useful for non-painful procedures, e.g. diagnostic ultrasound.

- For painful procedures, analgesia is also necessary.

- Cautions:

– Observe the child in department or ward (line-of-sight nursing) until return to baseline sedation score.

– Usually recovery occurs by 60 min after oral/intranasal administration and 30 min after i.v. administration.

– Midazolam potentiates the sedative effects of other drugs, e.g. opioids.

– Be prepared for a paradoxical reaction (agitation secondary to benzodiazepines).

– Midazolam should not be given to children with pre-existing respiratory insuffi ciency or neuromuscular disease (such as muscular dystrophy).

After the procedure

- Encourage the parent to remain with their child.

- Provide ongoing analgesia as needed.

- Document pain management techniques used and perceived success in minimising pain.

- Depending on the procedure, the child may need the opportunity to debrief. For example, staff and parents should focus on the helpful things the child did during the procedure. Staff may also like to suggest alternative techniques for any further procedures that may be planned.

Chronic or persistent pain management

Acute and chronic pain are distinct entities that require vastly different diagnostic and management skills; see Table 4.3.

Assessment

General principles

- Integrated multidisciplinary assessment and management is vital.

- Assess the physical and psychosocial causes for the child’s presentation.

- The factors maintaining persistent pain will determine specifi c treatment.

- An integrated approach with good communication between the involved healthcare providers is ideal.

Table 4.3 Comparison of the qualities and clinical course of acute versus chronic or persistent pain

| Acute pain | Chronic or persistent pain |

| • Tangible and understandable by the patient, family, friends and the treating doctor | • Often nothing to see and minimal evidence of tissue damage |

| • Usually brief, evoked by a recognised noxious stimulus and associated with an adaptive biological significance (e.g. protection of injured part to encourage healing) | • Often presents for prolonged duration |

| • Usually improves rapidly and is associated with functional improvement and pain score reduction on a daily basis | • May be evoked by minor trauma |

| • Usually related to the nature and extent of tissue damage | • Improves slowly over time with an undulating course |

| • Responds to pharmacological intervention | • Improvement and deterioration may be linked to life stresses |

| • Not necessarily related directly to the nature and extent of tissue damage | |

| • Does not always respond to pharmacological intervention | |

| • Often associated with secondary gains (e.g. school, sport or chore avoidance) |

History

- Is the pain:

– Nociceptive (arising from peripheral or visceral nociceptors)?

– Neurogenic (arising at any point from the primary afferent neurone to higher centres in the brain)?

– Psychogenic (occurs in the absence of any identifi able noxious stimulus or injurious process)?

- Fixed factors (age, cognitive level, previous pain experience, witnessed examples of how other family members react to pain).

- Situational factors (social and academic functioning at schools, learned pain triggers, independent pain-reducing strategies).

- Suffering (fear, anxiety, anger, frustration, depression).

- Pain behaviour (overt distress, secondary gain, consultation with multiple health professionals factors, moaning, splinting, complaining of pain). Pain behaviour is exacerbated where the following factors are present:

– Pain is central to communication (e.g. to receive a diagnosis or treatment).

– Similarly, there is an absence of reinforcement for non-pain communication.

– The child is fearful of increased pain (e.g. with movement).

– The meaning of pain is fear-inducing.

– The child and their parents may hold unhelpful beliefs and inadvertently maintain suffering, disability and dependency. The parents or child may obtain significant secondary gain from the child’s maintained pain.

- Assess for:

– Unhelpful belief systems of child and/or family (e.g. if pain were cured the other problems would not exist).

– Unrealistic expectations (e.g. it is others’ responsibility to fi x the problem).

– Functional disability (e.g. inability to play sport, socialise with peers, attend school).

Examine the painful site:

- What is causing the pain?

- Are there signs of complex regional pain syndrome? (see p. 69).

- Is there secondary deconditioning (e.g. muscle wasting, joint stiffening, tendon shortening)?

– These can occur rapidly, especially when fear of touch or movement exists.

Treatment

The goals are to eliminate pain, restore function and reduce pain behaviour. It is desirable to identify the cause of pain, treat and eliminate it; however, this is not always possible. Therefore management aims to achieve a more active and fulfi lling lifestyle, less constrained by pain.

Coordinate outpatient appointments to facilitate achieving these goals and minimising school absenteeism, time off work for parents and discouraging adoption of the sick role.

When to refer to a multidisciplinary pain clinic

A multidisciplinary team should ideally include a pain medicine specialist, physiotherapist, clinical psychologist, occupational therapist and child psychiatrist. The team should have access to an orthopaedic surgeon, neurosurgeon, paediatrician, paediatric rheumatologist and a rehabilitation specialist.

Refer when:

- Pain is more intense or persists longer than anticipated (e.g. after an injury).

- Character of pain is different to that expected.

- Pain responds poorly to medication.

- Loss of function results in secondary deconditioning (e.g. muscle wasting).

- Pain interferes with sleep, socialising with peers, school attendance and leisure activities.

- Pain behaviour manifests.

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is present.

- Pain is neuropathic.

Non-pharmacological techniques in chronic pain management

- Pain education:

– Help the patient understand that stress, anxiety and anger may contribute to pain. Identifying these stressors (often school or family) and managing these feelings more effectively may reduce or eliminate pain.

– Help the patient understand that pain does not always mean damage, and that pain is not a hindrance to return to function.

– Provide illness information (if one has been identifi ed) outlining implications for the future. This can minimise anxiety.

- Cognitive behavioural techniques address the (often unhelpful) thoughts that maintain pain and disability.

– Thought stopping or challenging techniques.

– Behaviour modifi cation techniques: based on modifying the consequences of the child’s pain experience and pain behaviour by rewarding positive behaviour.

- Pain coping strategies include

– Relaxation techniques: muscle relaxation via body awareness techniques, meditation, self-hypnosis or biofeedback.

– Distraction techniques: art, play or music therapy.

- Physiotherapy reconditioning programmes:

– Involve gradual return to function.

– Utilise: muscle stretches, postural exercises, reconditioning programmes and stress loading (e.g. ‘scrub and carry’ techniques for the upper limbs, weightbearing for lower limbs).

– Ultrasound treatment.

– Heat/cold treatment.

– Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS): activates large, myelinated primary afferent fi bres (A fi bres) that act through inhibitory circuits within the dorsal horn to reduce nociceptive transmission through small unmyelinated fi bres (C fi bres). TENS is more likely to be effective if pain responds to heat or cold.

- Pacing activity with reasonable goals.

- Management of setbacks.

- Sleep management.

- Family therapy:

– Addresses how family dynamics may maintain pain.

– Addresses how pain affects the rest of the family (e.g. lack of attention for well siblings).

- Parental counselling:

– Parents may inadvertently support illness and ignore non-pain activities.

– Addresses parental feelings of helplessness and loss of control.

– Equips parents with strategies to manage pain behaviour.

- Assertiveness training.

- School liaison:

– Address bullying.

– Modifi cations to allow return to school despite disability.

– Equip teachers with strategies to deal with pain behaviour.

– Graded return-to-school programmes with involvement and education of teachers.

- Vocational counselling.

- Hydrotherapy.

- Acupuncture.

Pharmacological techniques in chronic pain management

Paracetamol

Limit the dose for long-term administration to 60 mg/kg per day.

Steroids

- Triamcinolone used for joint injections, trigger point injections, tendon sheaths and neuralgias.

- Dexamethasone administered by iontophoresis for soft tissue injuries.

- Epidural steroid administration for localised nerve root irritation due to disc herniation without motor weakness.

NSAIDs

- Topical gels (diclofenac, piroxicam, ibuprofen).

- Oral and rectal preparations (described in Table 4.2).

Anti-neuropathic medications

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCADs)/newer noradrenergic and serotonergic reuptake inhibitors

Improve pain even if depression is not present by suppressing pathological neural discharges. Provides more effective analgesia, usually within days, once appropriate dose reached. Indications:

- Severe unremitting pain, especially if neuropathic.

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

- Associated depression.

- Poor sleep.

Amitriptyline is the most commonly used TCAD, starting at 0.2 mg/kg per day increasing over 2 weeks to 2 mg/kg per day. Administer as a single dose before bed to take advantage of sedative properties. Increase dosage until the desired treatment goal is achieved or side effects become unacceptable, e.g. dry mouth, morning somnolence.

Anticonvulsants (e.g. gabapentin or carbamazepine)

Indicated for neuropathic pain and CRPS.

Dosage should be in the therapeutic anticonvulsant range, although there is no evidence of any relationship between analgesic effect and the plasma level. Some recommend increasing the dosage to the point of side effects or analgesia. Gabapentin is not licensed for use in pain and incurs an out-of-pocket cost.

Opioids

- Only partially modulate central sensitisation.

- Usually ineffective in controlling neuropathic pain or pain secondary to CRPS.

- Indicated in cancer pain and nociceptive pain.

- Tramadol may be useful.

Other techniques can include ketamine, baclofen, clonidine, sympathetic and peripheral nerve blocks. Surgical techniques are rarely used in paediatrics.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), types I and II

This condition is of unknown aetiology and is more common in paediatrics than is generally realised. The diagnosis is clinical and treatment is easier when the condition is recognised early.

- Type I was formerly known as refl ex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD). It often occurs after a noxious stimulus to the affected limb (e.g. minor trauma or surgery). Symptoms are disproportionate to the inciting event.

- Type II was formerly referred to as causalgia. It differs from type I because it occurs after peripheral nerve injury.

Clinical manifestations

The affected area, usually a limb, manifests autonomic, sensory and motor symptoms consisting of:

- Pain:

– Regional non-dermatomal distribution.

– Hyperaesthesia (diffuse pain exacerbated by touch).

– Allodynia (pain elicited by a stimulus that is not usually painful).

- Temperature change (affected limb often colder).

- Changes in skin blood fl ow – often red/purple colour change.

- Abnormal sweating.

- Oedema.

- Loss of function/reduced range of motion

- Motor dysfunction – weakness, tremor, dystonia.

- Abnormal hair growth, skin and/or nail atrophy.

Investigations

- Acute phase markers – normal.

- Bone scan often abnormal – increased or decreased uptake.

- Plain radiograph – osteopenia in prolonged cases.

- MRI – diffuse marrow infi ltration is sometimes present.

Management

- Management requires early identifi cation, skilful physical therapy, avoidance of immobilisation and multidisciplinary pain team input.

- Consider psychiatric assessment, pharmacological and interventional techniques.

- Typified by continuous burning with an intermittent electric shock, stabbing or shootingtype discomfort.

- May be paroxysmal or spontaneous.

- Pain in an area of sensory loss.

- Pain in the absence of ongoing tissue damage.

- Associated with dysaesthesia (unpleasant, abnormal sensation, e.g. ants crawling on skin), allodynia and hyperalgesia (increased pain in response to noxious stimuli).

- Increased sympathetic activity may be present.

- Causes include CRPS type II, tumour, spinal cord injury, nerve damage (e.g. neuropraxia or avulsion, neuroma).

- Usually poor response to opioid medication.

- Consider the use of anti-neuropathic medications and early referral to a pain specialist and/or multidisciplinary pain management team if prolonged or refractory.

Pain in children and adolescents with disabilities

See also chapter 14, Developmental delay and disability, p. 170.

Pain assessment in individuals with cerebral palsy, cognitive impairment and/or communication diffi culties can prove challenging.

- No simple pain assessment tool exists.

- Caregivers are best placed to distinguish pain from ‘normal’ behaviour in the individual.

- Pain may manifest as crying, screaming, frequent waking, grimacing, arching, muscle spasm or self-injurious behaviour, but some individuals with cerebral palsy or intellectual disability may exhibit these behaviours without experiencing pain.

- Differential diagnosis includes seizures, muscle spasm, anxiety, depression and anger.

- A thorough search for the cause of pain will guide treatment options.

Night waking

- Occurs frequently and has implications for the functioning of the whole family.

- Most settle with re-positioning.

- Tricyclic antidepressants, via their analgesic and sedative effects, may be useful in reducing the frequency of waking.

USEFUL RESOURCES

- www.rch.org.au/anaes/pain – RCH Acute Pain Management Service Clinical Practice Guidelines. Links to many topics including: morphine by intermittent bolus guideline; opioid by infusion and patient controlled analgesia (PCA) .

- www.rch.org.au/rchcpg [Procedural Pain Management] – RCH guidelines for procedural pain management.

- www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide [Analgesia & Sedation] – RCH Clinical Practice Guidelines including links to Nitrous Oxide and Ketamine Guidelines.

- www.pediatric-pain.ca – Pediatric Pain Research Lab. Site created by a Canadian research group, devoted to the topic. Contains useful downloadable pamphlets and protocols.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree