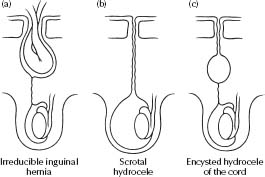

Inguinoscrotal conditions

The underlying pathological basis of an inguinal hernia, an encysted hydrocele of the cord or a scrotal hydrocele is the persistence of a patent processus vaginalis after the completion of testicular descent.

The causes of groin lumps in neonates are:

- Inguinal hernia – if irreducible, irritable baby, tender lump in the groin, unable to get above it.

- Encysted hydrocele of the cord, unable to be reduced – e.g. well baby, mobile lump.

- Undescended testes.

- Lymphadenitis with abscess formation – rare condition, often not diagnosed until operation.

Inguinal hernia (see Fig. 38.1a)

- Occurs when the patent processus vaginalis is large enough to allow bowel, omentum or ovary (in females) to protrude through the inguinal canal and sometimes, in males, down to the scrotum.

- The younger the child, the greater the risk of bowel or ovary becoming strangulated.

- Bowel strangulation in boys compresses the testicular vessels and may result in testicular ischaemia.

- Surgery is always required to prevent strangulation and this is done as a day case, except when the baby is <4 weeks of age.

Reducible inguinal hernia

See Table 38.1.

Irreducible inguinal hernia

- Urgent surgical referral is indicated.

- Most irreducible inguinal hernias can be manually reduced by a surgeon and surgery carried out within 48 h.

- Pain relief is appropriate to aid with reduction.

- The use of ice packs or traction is inappropriate.

Table 38.1 Reducible inguinal hernia

| Age at presentation | Timing of surgical consultation | Appropriate operating time |

| Birth–6 weeks | Day of diagnosis | Next available list |

| 6 weeks–6 months | Within few days | Within 2 weeks |

| 6 months–6 years | Within 2 weeks | Within 2 months |

Scrotal hydrocele, encysted hydrocele of the cord (see Fig. 38.1b,c)

In these conditions, the patent processus vaginalis is narrow and enables peritoneal fluid, but not abdominal contents, into the cord structures. A patent processus vaginalis often closes of its own accord in the first 18 months of life.

The important clinical signs of a scrotal hydrocoele are:

- Brilliantly transilluminable swelling.

- Narrow cord above the swelling.

- Swelling does not empty on squeezing and a normal testicle is felt in it.

- Non-tender.

If a hydrocele persists beyond 1 year of age, surgery is recommended and an inguinal herniotomy (i.e. division of patent processus vaginalis) is done as a day case.

Undescended testes

- Congenital: When the testis cannot be brought to the bottom of the scrotum, it is ‘undescended’. This is caused by incomplete migration of the gubernaculum to the scrotum. An assessment should be made by a paediatric surgeon between 3–6 months of life and an orchidopexy done at 6–12 months of age as a day case.

- Acquired: Some boys present with undescended testis later in childhood (4–10 years). This is the result of failure of elongation of the spermatic cord with age, caused by persistence of a fibrous remanent of the processus vaginalis. Surgery is recommended, if the testis does not remain in the bottom of the scrotum, to optimise fertility.

Acute scrotum

A child with a painful, tender or red scrotum should be seen by a surgeon as a matter of urgency. Without surgical exploration, it is usually impossible to differentiate between the two common causes:

- Torsion of the testis.

- Torsion of the testicular appendage.

Torsion of the testis

- Can occur at any age, but is most common in babies and adolescents.

- In older children it is characterised by more severe pain and vomiting.

- A testis lying horizontally in the scrotum indicates an anatomical predisposition to torsion and may cause intermittent testicular pain.

- Ultrasound is unreliable in distinguishing between torsion of the testis and torsion of the testicular appendage and often delays critical operative treatment.

Other causes

- Epididymo-orchitis is a rare disease in prepubertal boys who do not have urinary tract infections and should not be considered part of the initial differential diagnosis.

- Mumps orchitis is not seen before puberty. Do not treat with antibiotics.

The foreskin/prepuce

The foreskin is normally adherent to the glans at birth and remains so for a variable period of time. It is usually fully retractable by 3 years of age, but partial adherence is still normal up to 10 years of age. There is no need to retract the foreskin in preschool children.

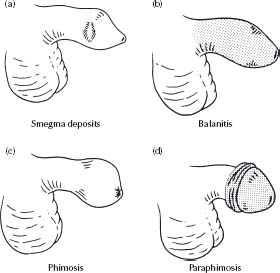

Smegma deposits

- Present as firm yellow-white masses beneath the prepuce in non-retractile foreskins (see Fig. 38.2a).

- Often confused with tumours or cysts of the penis, but are a normal variant and require no treatment.

Balanitis

- This is an infection under the foreskin with redness, inflammation, swelling and sometimes a white exudate (see Fig. 38.2b).

- Immediate treatment with local penile toilet, i.e., soaking in an antiseptic solution, local antiseptic ointment (e.g. neomycin eye ointment) beneath the foreskin and topical hydrocortisone 1% are used in mild cases. Oral antibiotics (e.g. co-trimoxazole) may also be added.

- If the whole penile shaft skin is red and swollen to the pubis, i.v. antibiotics may be required.

Phimosis

- This is scarring of the preputial opening, which causes:

– Urinary obstruction.

– Ballooning of the foreskin on micturition.

- It is often the end result of recurrent episodes of balanitis (see Fig. 38.2c).

- It usually requires circumcision if severe, although mild cases respond to topical 0.5% betamethasone valerate cream applied four times daily for 14 days.

Paraphimosis

- Acutely painful condition, which results from a retracted foreskin trapped behind the glans, forming an oedematous ring constricting the exposed and swollen glans penis (see Fig. 38.2d).

- Manual reduction should be attempted in all cases.

- To facilitate the procedure, use topical local anaesthetic cream (e.g. EMLA cream) 5 min before reduction.

- Ice and adrenaline-containing creams should not be applied.

- Failure to reduce the paraphimosis requires urgent surgical consultation.

Circumcision

- The indications for circumcision are phimosis and recurrent balanitis.

- There is no indication for neonatal circumcision.

- Hypospadias is an absolute contraindication, as the foreskin may be required for penile reconstruction.

- Circumcision is not required for cleanliness and <10% of Australian boys are currently being circumcised.

- It is an unnecessary operation with complications of surgery and anaesthesia.

- Common finding in newborn children; usually resolves in the first 12 months of life.

- If persists, operation as a day case is recommended before starting school.

- The operation is primarily cosmetic, although strangulation can occur during adult life (particularly during pregnancy).

Abdominal pain is a common symptom in children. Acute appendicitis must be distinguished from common causes of abdominal pain, including gastrointestinal and urinary tract infection and constipation.

Appendicitis

- The symptoms and signs of appendicitis are related to the degree of peritoneal irritation and the position of the appendix.

- Diagnosis is straightforward if there is localised peritonitis with guarding in the right iliac fossa; however, peritonitis may not occur in retrocaecal appendicitis and in pelvic appendicitis there may be only vague suprapubic tenderness.

- Repeated clinical examination and abdominal ultrasound may help identify these difficult cases. Rectal examination should not be done in children.

- Diagnosing appendicitis in the young child (<4 years of age) is difficult. It is important to refer a child who complains of persistent abdominal pain, even if this is associated with vomiting or diarrhoea. In particular, suspect significant peritonitis if the child does not allow abdominal examination.

Differentials

- Urinary tract infection may be excluded by urine testing (see chapter 35, Renal conditions). Blood, protein and white cells may all be present in the urine in acute appendicitis. Nitrites are more specific for urinary tract infections.

- Gastrointestinal infections often produce a local ileus but no peritonitis and are frequently distinguished by ‘squelchiness’ (secondary to air and fluid) in the right iliac fossa on examination.

Intussusception

- Consider in children aged 3 months to 2 years presenting with vomiting, intermittent abdominal pain and lethargy/pallor.

- These early symptoms should be acted on, rather than awaiting the classic ‘red currant jelly stool’, which is a feature of advanced disease.

- The abdominal mass is central, beneath the rectus abdominis on the right side, and is often difficult to feel.

- Ultrasound should be done to confirm the diagnosis. Contrast enema should not be used in the presence of peritonitis, significant dehydration or established bowel obstruction.

- An infant with suspected intussusception requires urgent surgical assessment and radiological investigations for diagnosis and treatment.

- Although an ultrasound may confirm the diagnosis, a contrast air or barium enema is required to reduce the intussusception.

These procedures should only be undertaken by experienced radiologists with a surgical team immediately available at a tertiary centre.

Malrotation and volvulus

- Green vomiting without an obvious septic cause is an indication for urgent surgical consultation, to exclude intestinal malrotation and the associated lethal complication of midgut volvulus. In regional settings, consider doing an urgent contrast study first, if surgical review is not immediately available.

- Initially, there may not be any clinical signs of abdominal disease. Abdominal distension is not usually seen in the early stages of presentation.

- Urgent surgical referral is necessary.

Pyloric stenosis

- Usually presents between 2 and 6 weeks of age (chronological age, regardless of prematurity).

- It may be difficult to diagnose and should be suspected when vomiting is projectile and if failure to thrive is present.

- Gastric peristalsis occurs due to pyloric obstruction and is clearly visible on the baby’s abdominal wall. When seen, it should prompt surgical referral.

- If the stomach is not grossly distended with fluid and/or air, the pyloric tumour is readily palpable.

- Ultrasound is only required if the diagnosis is unclear and the pyloric tumour cannot be felt.

Table 38.2 Vomiting in infancy

| Green vomit | Curdled milk |

| Differential diagnosis: | Differential diagnosis: |

| •Malrotation | • Pyloric stenosis |

| •Infection (gastroenteritis/meningitis/UTI) | • Gastro-oesophageal reflux |

| •Small bowel obstruction (rare) | • Infection (UTI/gastroenteritis/meningitis) |

| Management (after exclusion of major sepsis): URGENT SURGICAL REFERRAL | Projectile vomiting ± weight loss/gastric peristalsis: URGENT SURGICAL REFERRAL |

Metabolic complications

- Vomiting in these infants results in loss of gastric fluid (water and HCl). The kidneys can initially conserve H+, but once the baby becomes dehydrated, water and Na+ are conserved in exchange for K+ and H+. The resulting condition is hypovolaemia with alkalosis, low chloride and potassium. Even if serum K+ is normal, there is a total body potassium deficiency.

- A metabolic alkalosis (chloride < 100 mmol/L, pH > 7.45, bicarbonate > 32 mmol/L and sodium < 130 mmol/L) is present only in significant cases. Inappropriate rehydration with low-sodium-containing fluids can result in cerebral oedema.

Management

- An appropriate fluid for resuscitation is 0.45% (1/2 normal) saline with 5% dextrose. Potassium should be added once the baby is passing urine (refer to Table 38.3).

- If the baby’s weight before the onset of symptoms is known, fluid deficit is easily calculated. Maintenance requirements may be calculated at 100 mL/kg per 24 h.

– For example: a baby normally weighing 3 kg now weighs 2.7 kg.

– Deficit 300 gram (10% dehydration): replacement required 300 mL.

– Maintenance required: 300 mL/24 h.

– For resuscitation over 12 h, 450 mL is required in this period, i.e. 38 mL/h.

- For a simple guideline to facilitate fluid calculations if the baby’s weight is not known see Table 38.3.

- Cervical adenopathy: Enlargement of cervical lymph nodes is common with upper respiratory infections.

- Abscess: Consider bacterial infection with abscess formation in infants and children with large (2–4 cm) tender masses. There is often no overlying redness in cervical abscesses because the lymph nodes are beneath the deep fascia. Skin involvement occurs late in the disease. Fluctuance is the indication for surgical referral for incision and drainage.

- Mycobacterial lymph node infection (e.g. Mycobacterium avium complex): consider with evolution of indolent, non-tender, persistent lymphadenopathy in children 1–3 years of age. Purple discolouration in the overlying skin indicates an abscess, which requires surgical treatment.

- Other: large (>3–4 cm) or suspicious lymph nodes need a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Table 38.3 Fluid calculations in pyloric stenosis

| Clinical state | Fluids preoperative period/fi rst 12–16 h | Monitoring |

| Mildly dehydrated <5% | No bolus required | Check O2 saturations |

| Clinically well, reduced urine output | 1/2 normal saline & 5% dextrose with 20 mmol/l KCL in each litre | Monitor pulse, urine output |

| Electrolytes usually normal | Rate = 1.5 × maintenance for 12 h | Glucose, U&E, creatinine 12-hourly |

| Moderately dehydrated 5–10% | Bolus normal saline 20 ml/kg in 30 min | Monitor O2 saturations, pulse, BP and urine output |

| Mildly lethargic, pale, dry mouth | Then 1/2 normal saline & 5% dextrose with 30 mmol/l KCL in each litre | Glucose, U&E, creatinine 6–12-hourly |

| Poor urine output | Rate = 2 × maintenance for 12 h | |

| Low chloride +/– sodium | ||

| Severely dehydrated 10% | Bolus normal saline 20 ml/kg in 30 min | Monitor O2 saturations, pulse, BP and urine output |

| Lethargic, pale, mottled, dry mouth, no urine, tachycardia & may have low BP | Then 1/2 normal saline & 5% dextrose with 30 mmol KCL in each litre | Glucose, U&E, creatinine 4–6–hourly |

| Low chloride & sodium +/– low potassium | Rate = 2 × maintenance | |

| Continue up to 16 h or further if clinically indicated |

Table 38.4 Rectal bleeding

| Sick neonate | Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) |

| Malrotation | |

| Severe enteritis | |

| Well neonate | Ingested maternal blood |

| Bleeding disorder | |

| Anal fissure | |

| Well child: bright red blood | Anal fissure |

| Polyp (with mucus) | |

| Well child: dark blood | Meckel’s diverticulum |

| Peptic ulcer/varices | Inflammatory bowel disease |

See Table 38.4. See also chapter 27, Gastrointestinal conditions.

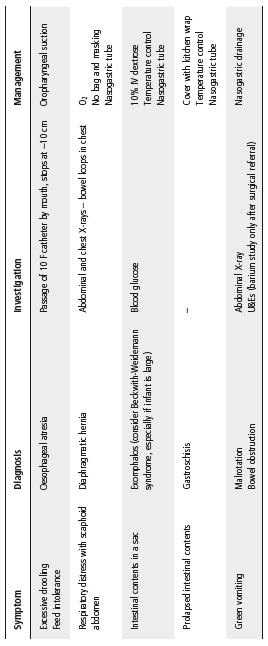

Urgent neonatal surgical conditions

Important warning signs

- Excessive drooling of frothy secretions from the mouth may suggest oesophageal atresia.

- Bile-stained or green vomiting is always abnormal (malrotation may be present and requires urgent treatment).

- Delayed passage of meconium (beyond 24 h) is abnormal and may indicate Hirschsprung disease.

- Inguinoscrotal hernias need urgent attention to avoid strangulation.

All the conditions below require urgent paediatric surgical consultation and transfer to a tertiary centre.

Oesophageal atresia

Excessive drooling or frothy, mucousy secretions from the mouth in a newborn suggests an inability to swallow. The test for oesophageal atresia is to pass a 10-French gauge catheter (which will not curl up) gently through the mouth.

- In the baby with oesophageal atresia, the catheter stops at 10 cm from the gums.

- In a normal baby, it passes to 20–25 cm and returns acid on litmus testing.

- First aid includes:

– Nil orally.

– I.v. fl.

– Frequent oropharyngeal suction (every 10–15 min), to prevent aspiration.

- Urgent transfer is required.

Table 38.5 Urgent neonatal conditions

Diaphragmatic hernia

- Respiratory distress in a newborn with a scaphoid abdomen suggests diaphragmatic hernia.

- Cardiac displacement and a chest radiograph showing bowel loops in the chest (left side more commonly) confirms the diagnosis.

- First aid is described in Table 38.5.

- If mechanical ventilation is required, only provide this via tracheal intubation; bag and mask ventilation may exacerbate respiratory distress by distending the bowel.

Exomphalos/gastroschisis

- These anterior abdominal wall defects place the child at risk of heat and water loss from the exposed surface of the sac (exomphalos) or bowel (gastroschisis).

- First aid is described in Table 38.5.

Sacrococcygeal teratoma

- Any lump over the coccyx of the baby should be assumed to be a teratoma until proven otherwise.

- Needs immediate referral at birth.

Ambiguous genitalia

Genitalia that are frankly ambiguous need urgent consultation with an experienced paediatric endocrinologist or surgeon on the first day of life (see chapter 25, Endocrine conditions).

- An enlarged clitoris in an apparent female is also abnormal and needs immediate referral.

- Hypospadias may overlap with ambiguous genitalia. This needs a careful initial assessment; if the diagnosis of hypospadias has been made, someone has already assumed the gender is male.

- If one or both testes are undescended, or the scrotum is bifid, or both, the baby should be treated as having ambiguous genitalia until proven otherwise, with immediate referral for further investigation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree