Asthma

Establishing the diagnosis and pattern of asthma

The two main components of asthma pathology include:

- Airway inflammation.

- Reactive airways (bronchoconstriction).

The important clinical features are:

- Wheeze.

- Shortness of breath.

- Chest tightness.

- Cough.

- Response of symptoms to short acting bronchodilators.

- Ask also for interval symptoms, e.g. symptoms at night (waking the patient), early in the morning, at rest during the day, during physical activity/sport.

Note: Cough alone, in the absence of wheeze, is rarely asthma.

Common triggers of asthma are:

- Upper respiratory tract infections (URTs).

- Exercise.

- Exposure to cold air.

- Allergen exposure.

Important clinical settings where asthma is more common:

- Individuals with allergic disease (perennial rhinitis, hay fever, eczema).

- First-degree relatives with asthma and/or atopic disease.

There may be few physical findings between acute attacks. Undertreated or chronic asthma may be associated with:

- Hyperinflation.

- Chest wall abnormalities, e.g. pectus carinatum or flaring of the lower ribs (Harrison’s sulci).

- Expiratory wheeze (generalised).

- Slowed growth parameters.

- Side effects of medication (e.g. oral candidiasis in those taking inhaled steroids).

Keep in mind other diagnoses if there are atypical findings, such as digital clubbing (suppurative lung disease), tracheal shift (mediastinal mass) or localised wheeze (inhaled foreign body).

In most cases the diagnosis of asthma in children is a clinical diagnosis.

- Although wheezing is a cardinal feature of asthma, there are a number of other causes for wheeze. In particular, wheeze in young children is common and may be due to small airway calibre rather than asthma. Infant and preschool patterns of wheeze include transient early wheeze and viral-associated wheeze. Most children with these patterns have stopped wheezing by 6 years of age.

- The natural history for most children with episodic (infrequent or frequent) asthma is that it will improve over time.

- The diagnosis of asthma is not always straightforward and a therapeutic trial of bronchodilator is sometimes required. In this case it is important that the treating doctor, referring doctor and family recognise that the trial of treatment does not lead to an inappropriate diagnostic label of asthma. An apparent response to therapy may be the natural course of the underlying disease as improvement occurs. An escalating requirement for treatment should trigger the need for reassessment (e.g. pneumothorax).

Investigations

Usually no investigations are required, but tests that may help with the diagnosis and management of asthma include:

Spirometry

- Children over the age of 6 years can learn to do spirometry accurately. However, it is important to note that peak flow measurements are unreliable in children and have a minimal role in diagnosis or in monitoring progress.

- Airway obstruction is defined as FEV1 <80% (predicted), FEV1/FVC <75%, MMEF 25–75 <67% (predicted).

- If there is evidence of airway obstruction then bronchodilator reversibility should be assessed (an improvement of FEV1 of 12% in absolute values).

- In most cases spirometry is unhelpful during an acute admission unless there is a difference between the perceived symptoms and objective clinical measures.

Exercise challenge

- May be used in children able to do accurate spirometry.

- 70% of children with asthma have exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.

- 15% reduction in FEV1 following exercise is considered significant.

- Graded dose inhalation of dry powder mannitol is a new alternative to the exercise challenge.

- Other challenges such as histamine and methacholine are not used in clinical practice for children.

Chest radiograph (CXR)

- CXR is not routinely required in either the acute or interval management of asthma.

- CXR may be required if there is evidence of an acute complication (e.g. mucous plugging) or patients with difficult-to-control, persistent asthma (particularly if they have not had a previous CXR).

- CXR is helpful if symptoms and signs are not wholly explained by asthma and may be caused by another disease (e.g. mediastinal mass, suppurative lung disease or foreign body).

Management of acute asthma

Also see chapter 1, Medical emergencies, p. 10, for the management of critical asthma.

Assessment of the severity of an attack

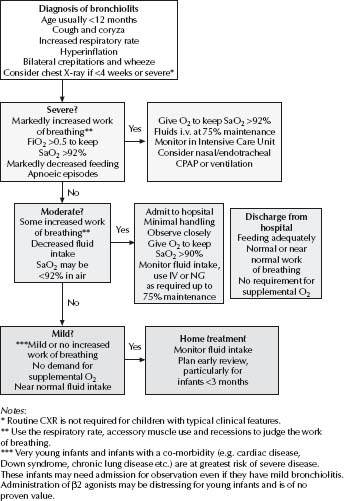

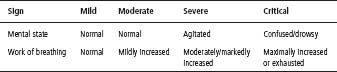

The severity of acute asthma can be classified as mild, moderate, severe or critical. The most reliable indicators are mental state and work of breathing (comprising accessory muscle use and recession). See Table 36.1.

Patients with an acute exacerbation of asthma requiring salbutamol every 3 h at home should be assessed by their Local Medical Officer or in the emergency department. Parents who are familiar with their child’s asthma can initiate prednisolone at home at the start of an exacerbation, although there is limited evidence for this practice.

- The initial arterial O2 saturation (SaO2) in air, heart rate and ability to talk should be used as additional features in assessing the severity of acute asthma.

- Wheeze intensity, central cyanosis, pulsus paradoxus, peak expiratory flow are not reliable for the assessment of the severity of acute asthma.

- Arterial blood gases, CXR and spirometry should not be routinely used in assessing the severity of acute asthma

Table 36.1 Assessment of the severity of an acute asthma attack

Table 36.2 Treatment of an acute asthma attack

1 Salbutamol (100 mcg/puff) delivered by pMDI and spacer – 6 puffs if <6 yo, 12 puffs if ࣙ6 yo.

2 Reduce frequency of β2-agonist if improving. If no change, continue 20 minutely β2-agonist. If deteriorating, treat as critical.

3 Salbutamol 0.5% solution delivered by nebuliser.

4 Ipratropium (40 mcg/puff) delivered by pMDI and spacer – 2 puffs if <6 yo, 4 puffs if ࣙ6 yo.

5 Salbutamol 5 mcg/kg per min for 1 h i.v. (load), then 1 mcg/kg per min infusion.

6 Aminophylline loading dose 10 mg/kg (max. 250 mg) over 1 h (if patient previously taking theophylline, measure serum level to decide need for loading dose); then infusion 1.1 mg/kg per hour if age 1–9 years, 0.7 mg/kg per hour if 10+ years. Aminophylline and salbutamol must be given by separate i.v. lines.

Hospital discharge and home treatment

Patients should be discharged from medical care when they are stable and can be cared for at home. This usually corresponds to a requirement for salbutamol 3–4 hourly or less frequently and no oxygen requirement for 24 h. Education of caregivers is an important component of this process.

Writing an individual asthma action plan assists caregivers in treating asthma in the current and subsequent episodes. The key elements in the plan are:

- Daily treatment.

- Treatment of minor symptoms.

- Treatment before exercise if it is a known trigger.

- Treatment of acute exacerbation.

- Emergency plan.

Drug delivery

Ensure that delivery devices are appropriate to the patient’s age. Selection of appropriate delivery system is crucial for good asthma management. Allow older children and adolescents to choose the inhaler and tailor the medication to the delivery system.

- All metered-dose inhaler doses are given through a spacer. In young children a mask is firmly applied to the face, and older children put their lips around a mouthpiece.

- Shake the puffer initially and then after every three puffs.

- Load with one puff at a time (and repeat).

- If the child uses tidal breathing, allow 5–6 breaths. If the child is able to take larger breaths (this is best), wait until they take 1–2 breaths.

- Frequency: in hospital, doses may be given frequently as indicated by severity and response. The use of oxygen between treatments does not preclude using a spacer.

- Spacers should be washed in household detergent weekly to reduce static and then air-dried (spacers should not be rinsed, rubbed or towel dried).

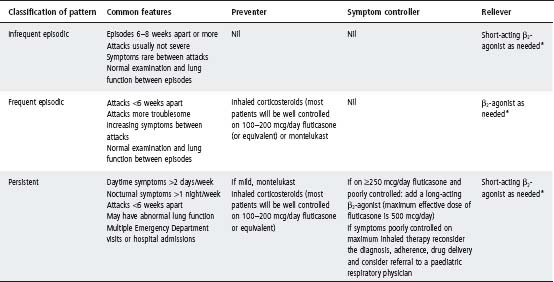

Table 36.3 Drug delivery devices

| Delivery system | Age |

| Pressurised metered dose inhaler (pMDI) | >8 (reliever only, mild symptoms) |

| PMDI + small volume spacer | |

| Mask 0–3 years | No mask 3–5 years |

| PMDI + large volume spacer >5 years | Turbuhaler >8 years |

| Accuhaler >8 years | Autohaler >8 years |

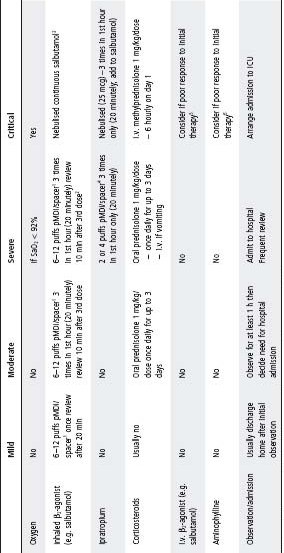

Table 36.4 Patterns of asthma and Interval treatment

All asthma preventers and symptom controllers prescribed as pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDIs) should be delivered through a spacer regardless of the age of the patient. All patients using ICS should rinse their mouths afterwards, regardless of the inhaler.

Principles of interval asthma management

After establishing the diagnosis it is important to determine the pattern of asthma in order to prescribe the appropriate treatment (see Tables 36.4 and 36.5).

A number of issues should be attended to at subsequent check-ups, including:

- Symptom review, in particular nocturnal and exercise symptoms.

- Review of asthma action plan and medication regimen.

- Adherence with medication.

- Avoiding precipitants (e.g. allergens).

- Avoidance of cigarette smoking (active and environmental).

- Monitoring of growth and development.

Aetiology

Respiratory viruses are the most common cause of bronchiolitis in young infants. The most common is respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Bronchiolitis is a generalised lower respiratory tract infection, but RSV infection can also cause lobar pneumonia.

Clinical features

- Cough, wheeze, tachypnoea, apnoeas, fever and poor feeding in an infant.

- There may be signs of respiratory distress including tracheal tug, recession, use of accessory muscles, grunting.

- Crackles and wheeze on auscultation

- Severe bronchiolitis is associated with respiratory failure

- Young infants (<6 weeks) are at risk of apnoeas.

Management

See Fig. 36.1.

- CXR and nasopharyngeal aspirates are not routine investigations for bronchiolitis.

- Infants <3 months and those with severe bronchiolitis are more likely to become hyponatraemic (due to the syndrome of ‘inappropriate’ increased ADH secretion (SIADH)) and warrant close attention to fluid balance. See also p. 73, Fluid and electrolyte therapy.

Aetiology

- Respiratory viruses are the most common cause of pneumonia in young infants in developed countries. There is generally only mild to moderate constitutional disturbance. There may be scattered inspiratory crackles on auscultation.

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae is the most common pathogen in children >5 years old and is an under-recognised cause of pneumonia in younger children. Typically symptoms develop over several days before the cough, often with a systemic illness. Cough is prominent and crackles may be focal or widespread. Children are usually unwell, may have headache and focal signs are present in the chest.

- Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common bacterial pathogen in all age groups, followed by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae and Staphylococcus aureus. Group A â-haemolytic streptococcus is less common but may cause severe pneumonia. Many older children can be managed at home, but most <24 months should be admitted to hospital.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree