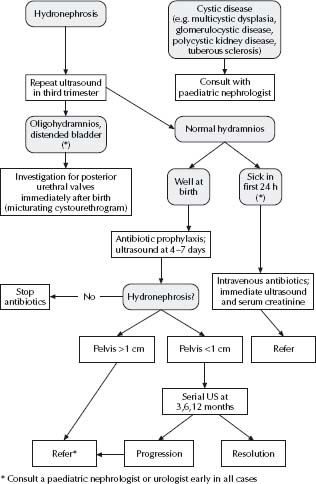

Antenatal abnormalities

See Fig. 35.1.

Clinical features

Infants and younger children

- Fever can be the sole symptom.

- Non-specific symptoms such as lethargy, irritability, vomiting and poor feeding are common.

- Offensive urine is neither sensitive nor specific for UTIs in children.

Older children

- Fever, dysuria, urgency, frequency, incontinence, macroscopic haematuria, abdominal pain.

Remember that finding a VTI in a sick child does not exclude another site of serious infection (e.g. meningitis).

Risk factors

- Previous UTI.

- Structural abnormality of renal tract, e.g. duplex systems, posterior urethral valves.

- Vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR).

- Strong family history.

Pathogens

- Escherichia coli (80%).

- Enterococcus faecalis (10%).

- Other Gram-negatives – Klebsiella, Proteus, Enterobacter, Citrobacter.

- Other Gram-positives – Staphylococcus saprophyticus.

Associated renal tract abnormalities

40% of children with UTI have underlying renal tract abnormalities:

- VUR 40%

- Reflux-associated nephropathy (renal scarring) 12%.

- Pelvic-ureteric junction (PUJ) or vesico-ureteric junction (VUJ) obstruction 4–6%.

- Other congenital abnormalities.

Diagnosis

Urine infections are diagnosed by bacterial growth on midstream urine (MSU), catheter (CSU) or suprapubic aspirate (SPA) specimens of urine. A clean catch specimen is prone to contamination.

Urine ‘ward test’ strips

These are useful as a screening test in a child with low suspicion of a UTI (>6 months, without known renal tract abnormality and with an alternative focus for fever). Ward test should not be used in a child with a high chance of a UTI. The ward test strips for leucocytes or nitrites are negative in up to 50% of UTIs in children. This is because the production of nitrites by bacteria is time-dependent and infant bladder capacity necessitates frequent voiding.

Bag urine specimen collection

- Do not send for culture.

- Use for chemical strip screening only.

- In sick infants or those where the suspicion of UTI is high (e.g. renal tract anomaly or previous UTI), a bag specimen should not be taken, as it only delays the diagnosis. A SPA (preferred) or CSU sample should be obtained as part of the septic workup (see chapter 30, Infectious diseases).

Midstream urine specimen collection

This can be obtained from children who are able to void on request (usually by 3–4 years of age). The child’s genitalia are first washed with warm water. In girls the labia should be separated. The child is asked to void. After passing the first few millilitres, a specimen is collected.

- A pure growth of 108 c.f.u./L in a MSU is proof of a UTI.

- A pure growth of >105–108 c.f.u./L in a MSU is suggestive of a UTI (correlate with clinical setting).

Catheter specimen collection

See chapter 3, Procedures.

- These are useful in infants after a failed SPA or in older children who are unable to void on request. A pure growth of >105 c.f.u./L indicates infection.

Suprapubic aspirate collection

See chapter 3, Procedures.

- This is the preferred method of urine collection in infants. Aspirated urine should be sterile; hence any pure growth of bacteria indicates infection.

Other investigations

- Blood culture and electrolytes.

- Do not omit a lumbar puncture in a sick child just because UTI has been diagnosed. All infants <3 months with VTI should have a lumbar puncture. Consider a lumbar puncture in all infants aged 3 months–2 years with UTI.

Management

- Most infants <12 months of age with a UTI require benzylpenicillin 60 mg/kg i.v. (max. 2 g) 6 hourly and gentamicin 7.5 mg/kg i.v. (<10 years) or 6.0 mg/kg i.v. max. 240 mg (>10 years) daily.

- In children who are well and not vomiting (even those with clinical pyelonephritis), a course of oral antibiotics has been shown to be as effective as i.v. antibiotics (see Antimicrobial guidelines). Antibiotic sensitivity should be checked when available (usually at 48 h).

- In children at high risk of recurrent UTI (see Risk factors, p. 488) prophylactic antibiotics should be commenced immediately after the treatment antibiotic course has finished. Their role in children <12 months with first episode is debated.

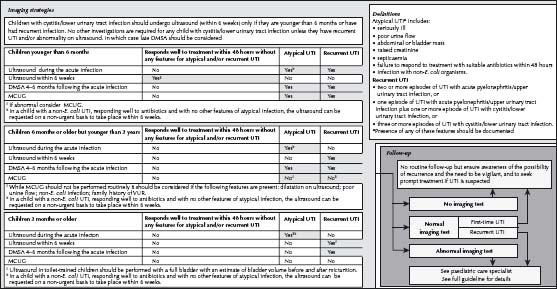

- If used, prophylactic antibiotics should be continued until the minimal initial imaging investigations have been done (see below). A decision regarding continuing prophylaxis is then made on the basis of the anatomy of the urinary tract and other clinical indicators (see Fig. 35.2). The guidelines recently released by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommend fewer investigations than in many previous guidelines and remain somewhat controversial. See also Antimicrobial guidelines. The use of prophylactic antibiotics is an area of controversy with ongoing research.

- For neonates <1 month old or preterm infants, discuss with a specialist.

Subsequent investigations (see Fig. 35.2)

- The extent to which a child should be investigated following a UTI is of international debate, and should be tailored for the individual patient.

- Ultrasound:

– All children <6 months old presenting with a first UTI should have an ultrasound (refer to National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) UK guidelines).

– Consider an ultrasound in children >6 months old presenting with a first UTI.

- Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scan:

– This nuclear medicine scan is done at least 6 months after the UTI to look for renal parenchymal defects (primarily renal scarring).

- Micturating cystourethrogram (MCU):

– Performed to detect VUR.

– It also provides good anatomic detail of the bladder and urethra.

– Radiographic contrast is instilled in the bladder via a urethral catheter and subsequent radiographs taken to image the bladder and urethra.

- Siblings of children with VUR:

– In children with VUR, their siblings will also have (or have had) VUR in 50%. – Consider an ultrasound scan in such cases.

Reproduced with permission from the UTIC guideline, commissioned by NICE to the National Collaborating Centre for Women and Children’s Health (NCC–WCH), UK

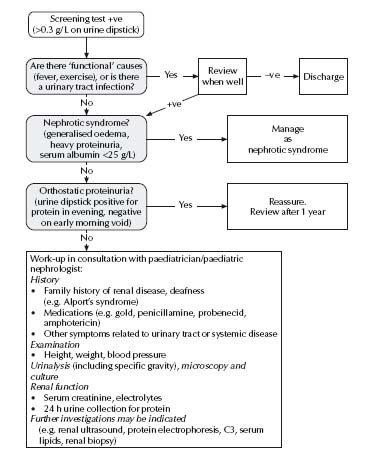

Isolated proteinuria

See Fig. 35.3.

Nephrotic syndrome

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome is made on the basis of proteinuria (>40 mg/m2 per hour on a recumbent urine, usually >3 g/1.73 m2 per day; urine protein/Cr ratio >0.4 g/mmol; usually 3+ to 4+ on dipstick testing), generalised oedema, hypo-albuminaemia (<25 g/L) and hypercholesterolaemia (>4.5 mmol/L).

Investigations

- Electrolytes, urea, creatinine.

- Albumin.

- C3, C4, CH50.

- Cholesterol.

- ANA, Igs.

Management

Exclude life-threatening complications

- Sepsis (e.g. peritonitis) – secondary to urinary loss of immunoglobulins.

- Symptomatic hypovolaemia (e.g. cool extremities and postural hypotension) – secondary to loss of albumin and subsequent contraction of intravascular space.

- Symptomatic oedema (e.g. marked ascites, respiratory distress with pleural effusions and skin breakdown).

- Symptomatic thromboembolism (e.g. venous sinus thrombosis: convulsions and a reduced conscious state; deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) – secondary to increased hepatic synthesis of plasma fibrinogens, urinary loss of antithrombin III and haemoconcentration.

Admit to hospital

- For initial observation and patient and family education

Medication

Note: Minor variations in protocol may exist between centres.

- Prednisolone:

– 60 mg/m2 per day as a single dose up to max. 80 mg/day for 4 weeks. Then:

– 40 mg/m2 per alternate day for 4 weeks.

– 20 mg/m2 per alternate day for 4 weeks.

– 15 mg/m2 per alternate day for 4 weeks.

– 10 mg/m2 per alternate day for 4 weeks.

– 5 mg/m2 per alternate day for 4 weeks.

- Phenoxymethylpenicillin: 12.5 mg/kg (max. 1 g) oral twice daily until oedema clears (to prevent pneumococcal sepsis).

- Aspirin: 10 mg/kg per alternate day until oedema clears (to reduce the incidence of arterial thromboses).

Note: The long-term prognosis of nephrotic syndrome is dependent on the response to prednisolone.

For m2 formulae, see Appendix 4, p. 614.

Treatment of complications

- Symptomatic oedema: concentrated albumin (i.e. 20%) 1 g/kg (5 mL/kg), i.v. over 4 h with frusemide 1 mg/kg at 2 and 4 h after the start of the infusion.

- Circulatory insufficiency: concentrated albumin (i.e. 20%) 1 g/kg (5 mL/kg), i.v. over 4 h. (Administer frusemide only if the circulation is markedly improved at the end of the infusion – it is dangerous in hypovolaemic patients.)

- Thromboembolism: systemic anticoagulation with heparin, followed by warfarin for 3–6 months.

- Sepsis: high-dose antibiotic therapy to cover Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Escherichia coli (e.g. cefotaxime 50 mg/kg (max. 2 g) i.v. 6 hourly).

- Suspected primary peritonitis:

– Peritoneal tap to establish diagnosis.

– If early diagnosis and minimal symptoms, antibiotic therapy alone may be sufficient.

– Usually requires laparotomy for a peritoneal lavage.

Additional treatments

If the patient does not respond to steroids, refer to a specialist for consideration of cyclophosphamide or cyclosporin A treatment.

Indications for renal biopsy

- Age: <1 year of age.

- Failure to respond to prednisolone within 3–4 weeks of treatment using 60 mg/m2 per day, either at diagnosis or with relapse.

- Nephritic/nephrotic syndrome (increased blood pressure, moderate haematuria and renal impairment without evidence of peripheral circulatory insufficiency).

- Low complement (C3).

Relapse

Most (75%) patients relapse.

- This is usually precipitated by a febrile illness or an allergic reaction.

- Four days of heavy proteinuria (>100 mg/dL; i.e. 3+ to 4+ on urine dipstick) distinguishes relapse from transient proteinuria associated with a febrile illness.

- Treat with: prednisolone 60 mg/m2 per day till proteinuria dip test result in 0, trace or +. Then:

– 40 mg/m2 alternate day for 2 weeks.

– 20 mg/m2 alternate day for 2 weeks.

– 15 mg/m2 alternate day for 2 weeks.

– 10 mg/m2 alternate day for 2 weeks.

– 5 mg/m2 alternate day for 2 weeks.

Also use penicillin and aspirin if the patient becomes oedematous (see p. 495).

Indications for referral

Refer to a specialist in cases of:

- Nephritic/nephrotic syndrome.

- Complications.

- Failure to respond to steroids in 2–3 weeks.

- Frequent relapsing nephrotic syndrome or steroid dependence.

Causes of macroscopic haematuria

- Infection.

- Glomerulonephritis (GN):

– Post infectious GN (common)

– IgA GN (common)

– Rapidly progressive crescenteric GN (rare but important), e.g. SLE, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) GN.

- Trauma.

- Calculi.

- Tumour.

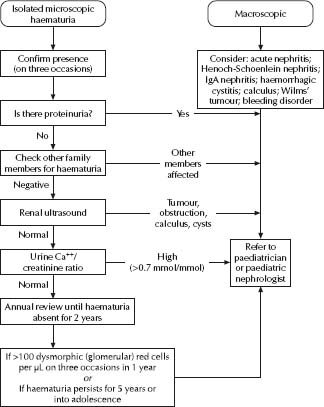

Causes of microscopic haematuria

- Febrile illness.

- Thin membrane nephropathy.

- Causes of macroscopic haematuria (as above). See Fig. 35.4.

Measurement of blood pressure

- Use a cuff with a bladder that covers at least 75% of the length of the upper arm.

- Take in the right arm, with the patient sitting; if initially increased, retake after resting quietly.

Definition

The 95th percentiles for blood pressure (BP) at different ages in childhood are shown in Table 35.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree