Neonatal orthopaedic conditions

Developmental dysplasia of the hip

This condition was previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip; however, not all cases are present at birth and the hips are not necessarily dislocated. Risk factors are breech delivery, oligohydramnios, Caesarean section, family history, congenital anomalies (especially foot abnormalities), being first-born and female.

Diagnosis

General screening

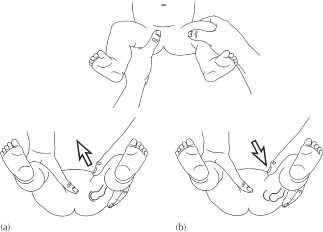

All neonates should have a clinical examination for hip joint instability – the Ortolani and Barlow tests. The baby should be relaxed. With the knee flexed, the thumb is placed over the lesser trochanter and the middle finger over the greater trochanter. The pelvis is steadied with the other hand and the flexed thigh is abducted and adducted. Any clunk or jerk where a dislocation reduces allowing the hip to abduct fully, is a positive Ortolani’s sign. The demonstration of acetabular dislocation by levering the femoral head in and out of the acetabulum is a positive Barlow’s sign (see Fig. 34.1).

Selective screening

Infants in high-risk groups and those with an abnormal routine clinical screening examination should have an ultrasound examination of their hips.

- As clinical diagnosis can be difficult and ultrasound has diagnostic limitations, the repeated examination of children with risk factors during the first year of life is important.

- When the ossification nucleus of the femoral head develops, between 3 and 9 months, the preferred mode of imaging changes from ultrasound to plain radiograph. Generally use ultrasound up to 6 months of age and radiography thereafter.

Management

The earlier the diagnosis, the easier the management.

- Most neonates can be successfully treated by abduction bracing with a Pavlik harness.

- Operative treatments, including open reduction, may be required with later diagnosis.

Club foot (congenital talipes equinovarus)

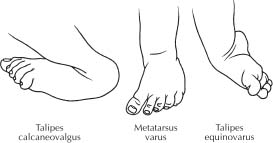

Most infants with abnormal-looking feet are said to have ‘talipes’. However, the majority have postural problems such as talipes calcaneovalgus (excessive dorsiflexion and eversion), metatarsus varus (adduction of the forefoot) or postural talipes equinovarus (see Fig. 34.2). These deformities are usually mild and mobile; that is, they correct easily and fully with the pressure of one finger. They resolve spontaneously with no treatment.

The true club foot deformity is more severe and is often stiff. The foot is in equinus, with the hind foot in varus and the forefoot supinated.

Management

- All require manipulation and casting.

- Soft tissue surgery is required for many.

- Bone surgery is required for a few.

Torsional and angular deformities in children

Many children are seen with normal angular or torsional variants of the lower limbs. It can be difficult to distinguish physiological variation from pathological conditions. The range of ‘normality’ is wide, but physiological variations can result in as much parental anxiety as pathological disorders.

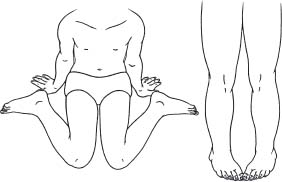

Intoeing

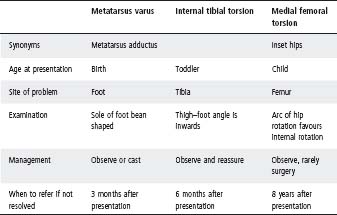

Intoeing in childhood can be due to metatarsus varus, internal tibial torsion or medial femoral torsion. See Table 34.1, Figures 34.3 and 34.4.

Out-toeing

Infants and toddlers have restricted internal rotation at the hip because of an external rotation soft tissue contracture, not retroversion of the femur.

Infants

- Present with a ‘Charlie Chaplin’ posture between 3–12 months.

- The child weight-bears and walks normally.

- Resolution occurs with no treatment.

Table 34.1 Intoeing in childhood

Children

- May be due to neurologic disorder.

- Surgery may be necessary.

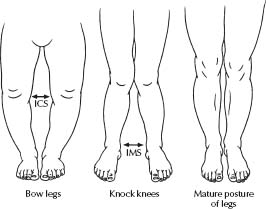

Bow-legs (genu varum)

The vast majority are physiological. Rare causes include skeletal dysplasias, rickets and Blount’s disease (tibia vara).

Presentation

- Toddlers are usually bowed until 3 years of age.

- Physiological bowing is symmetrical, not excessive and improves with time.

Management

Monitor intercondylar separation (ICS; see Fig. 34.5). Refer when ICS is >6 cm, is not improving or is asymmetric.

Knock-knees (genu valgum)

Again, the vast majority are physiological. Rare causes are rickets and trauma.

Presentation

- Children are usually knock-kneed from 3 to 8 years.

- Physiological knock-knee is symmetrical, not excessive and improves with time.

Management

- Monitor the intermalleolar separation (IMS; see Fig. 34.5).

- Refer if IMS >8 cm.

Note: Most children with bow-legs or knock-knees are normal, with <1% having an underlying problem.

Flat feet (pes plano valgus)

This condition is painless and asymptomatic.

Note: If painful or stiff, referral is needed.

Causes

- Physiological (in the vast majority): all newborns have flat feet due to fat that fills the medial longitudinal arch; 80% of children develop a medial arch by their sixth birthday.

- Tarsal coalition (in older children and adolescents only).

Management

- No treatment is required unless the condition is painful or stiff.

- The condition is unaffected by orthotics or exercises.

- Most cases resolve spontaneously.

The management of fractures and dislocations is an integral part of the overall management of the trauma patient. Common fractures in children involve the wrist, elbow, clavicle, distal tibia, fibula and femur. Each has distinct management strategies but there are common themes.

Assessment

Patients presenting with a suspected fracture or dislocation require a full evaluation of the fracture and exclusion of damage to other structures.

An accurate history of the mechanism of injury will determine which structures may potentially be damaged.

Box 34.1 Consider child abuse in infants with fractures (see chapter 17, Child abuse)

The following details must be sought for every child presenting with an injury: age, developmental stage (including motor capabilities), where injury occurred, whether witnessed (by whom), what actually happened, what is suspected if not witnessed, any delay in presentation, history of previous injuries. Inconsistency of the history between carers or on repeated telling should raise concern.

Examination

- Closed or open fracture (the latter will require operative intervention).

- Deformity or swelling. Note: Acute swelling in children usually indicates a fracture.

- Neurological status distal to the injury.

- Peripheral pulses – if the blood flow to the limb is compromised, emergency orthopaedic consultation is necessary.

- Associated injuries.

Management

- The affected limb should be splinted by a board or plaster slab before radiography.

- Analgesia (usually parenteral) is required (e.g. morphine 0.05–0.1 mg/kg dose i.v.). See chapter 4, Pain management.

- A radiograph should be obtained of the suspected fracture site, with additional views to include the joints above and below the suspected fracture site. Anteroposterior and lateral views should be obtained.

- If the arm appears bent on examination or if the angle between the shaft of the bone and the fractured fragment is >15–20°, manipulation of the fracture needs to occur before the placement of a plaster. Forearm fractures in children 5 years or older can usually be manipulated using a local anaesthetic block (e.g. Bier’s block, see chapter 3, Procedures).

- If the fracture involves both cortices of the bone, plaster the joints above and below (e.g. above the elbow for a forearm fracture).

- A simple undisplaced greenstick or buckle fracture can be treated in a short cast/backslab.

Home treatment after a full plaster

- Elevate the limb above the heart level for the next 24–48 h.

- Forearm: a sling should only be worn after this period and the hand should not be below the elbow while in the sling.

- Lower limb: crutches should only be used by children over 6–7 years of age, who are co-ordinated enough to use them.

- Written plaster instructions should be explained and given to parents.

Follow-up

For patients who have had a manipulation of fracture or a fracture involving both cortices of the bone, a repeat radiograph should be obtained in 1 week to ensure the correct position is maintained. Plaster should remain in place for 3–6 weeks, depending on the degree of injury and bone involved. Following the removal of the cast, the bone is still at risk of re-fracture for the next 8–12 weeks; therefore, contact sports are not recommended during this period.

Box 34.2 Description of fractures

It is helpful to use a specific, technical vocabulary to describe fractures for the purposes of documentation, and discussion with colleagues. Important features include:

- The anatomical site of the fracture: Which bone? Which side? For example, right humerus or left tibia. In most long bones it is helpful to specify whether the fracture is in the upper, middle or distal third of the bone.

- The fracture type: i.e. open or closed. An open fracture has a wound which communicates with the exterior, a closed fracture has an intact soft tissue envelope.

- The appearance of the fracture line: e.g. transverse, oblique, spiral or comminuted (more than one fragment).

- Whether there is a specific type of fracture. Children’s bones are more elastic and less brittle than adult bones. Consequently they are more likely to bend and buckle, rather than crack or break. This results in two common patterns of fracture that are seen in children and not in adults:

– Greenstick fractures.

– Buckle fractures.

- The displacement of the fracture, e.g. undisplaced, angulated or displaced. Angulation is described by drawing a line along both major fragments and measuring the angle of intersection. Displacement is best described by comparing the position of the bone ends with the width of the bone at that point e.g. half a diameter displaced or completely displaced.

- Fractures of the expanded ends of long bones are usually described as metaphyseal, and injuries to the growth plate are described according to the Salter–Harris classification (see Fig. 34.6).

From these terms, a complete description of any fracture can be given that should be meaningful to a colleague who has not seen the radiographs. For example, a femoral shaft fracture might be described as a closed, displaced, midshaft fracture of the left femur with 30° of angulation and one complete diameter of displacement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree