Febrile convulsions

- Febrile convulsions (FC) are usually brief, generalised seizures associated with a febrile illness, in the absence of any CNS infection or past history of afebrile seizures.

- Most FC occur in the context of a genetically determined, age-dependent seizure disorder in which the child has a tendency to have seizures with fever.

- Simple FC are brief, generalised and single.

- Complex FC are either focal, >15 min, or multiple in a 24 h period.

- FC occur in 3–4% of children aged 6 months to 5 years and are recurrent in 1/3.

- In otherwise healthy children, FC are not accompanied by an increased risk of intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, other neurological disorders or death. However, there is a modest increase in the risk of epilepsy.

Management

- Stop a continuing convulsion (>10 min duration) with i.v. or rectal diazepam 0.2–0.4 mg/ kg (max. 10 mg).

- General temperature-lowering measures such as removing clothing and administering paracetamol 15 mg/kg may help reduce symptoms of fever.

- A careful search for the cause of fever is required. Most will be due to viral respiratory infections.

- A lumbar puncture need not be done routinely following a simple FC, but meningitis should be considered in any unwell child, especially when there is a persistently depressed conscious state and in children with multiple or prolonged convulsions. The younger the child, the higher the index of suspicion of meningitis.

Recurrence of FC is more likely if seizures occur in early infancy and if there is a family history of FC. As FC are usually benign and as anticonvulsants may have significant side effects and do not alter long-term prognosis, they are not routinely recommended for children with recurrent FC. In some circumstances (e.g. children with a history of prolonged FC) parents may be taught to administer rectal diazepam or buccal midazolam.

About 3% of children with FC subsequently develop afebrile seizures (epilepsy). This is in comparison to the prevalence of epilepsy of 0.5% of all children. The risk is greater with:

- Previous abnormal neurological development.

- A history of epilepsy in first-degree relatives.

- Prolonged (>10 min) FC.

- Focal features present during, or after, the FC.

- Multiple convulsions during a single febrile episode.

When counselling parents, remember that many will have felt that their child nearly died. The very low risk of neurological complications, the excellent prognosis for eventual remission of FC, but the 1 : 3 risk of FC recurrence, need to be emphasised. Advice on the management of future febrile illnesses and FC is required. A follow-up visit is recommended to review FC and minimise the development of ‘fever phobia’ in the parents. An electroencephalogram (EEG) is of little value in single or recurrent, simple or complex FC.

Epilepsy (defined as two or more unprovoked seizures) occurs in approximately 0.5% of children. Seizures may be focal (partial) and/or generalised and the aetiology may be idiopathic (genetic) or symptomatic (malformation, tumour, scar, degenerative).

Benign focal (idiopathic partial) epilepsies of childhood

- Onset is typically in mid-childhood (peak 7 years).

- Seizures are commonly nocturnal or early morning. In the centro-temporal (Rolandic) variety, they are usually focal motor or sensory phenomena related to the face, mouth or jaw. The occipital variety may have visual manifestations. Secondarily generalised tonic– clonic seizures may also occur.

- On EEG, spike discharges typically occur in the centrotemporal or occipital region.

- Imaging is only necessary if clinical or EEG features are atypical or if seizure control is difficult.

- The prognosis is excellent as the seizures are usually infrequent and remit before the teenage years.

- Treatment is only indicated in children with frequent or prolonged seizures. Low-dose carbamazepine or sodium valproate is used for 1–2 years given the spontaneous remission of seizures.

Idiopathic generalised epilepsies

- This term describes a group of recognisable childhood epilepsies characterised by recurrent generalised tonic–clonic, absence or myoclonic seizures of presumed genetic cause.

- The first seizure usually occurs at 4–16 years of age, in an otherwise normal child who may have a history of prior FC.

- The EEG invariably shows intermittent generalised spike wave patterns.

- The prognosis is generally good for seizure control and remission in later childhood or adulthood.

- Idiopathic generalised epilepsy syndromes include childhood and juvenile absence epilepsies, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, and epilepsy with isolated tonic–clonic seizures.

Symptomatic focal epilepsies

- This term describes a heterogeneous group of seizure disorders in which children have focal (partial) seizures from particular brain regions, due usually to an underlying developmental (congenital) or acquired lesion.

- Complex partial seizures and focal motor seizures are the main seizure type. The former is usually manifest by arrest of activity, staring, autonomic disturbances, semi-purposeful automatic movements (automatisms) and altered conscious state, sometimes preceded by an aura. Specific seizure manifestations depend on the brain region involved. Seizures may secondarily generalise.

- Seizures typically occur in clusters and may be difficult to treat.

- Children may have associated learning and behavioural problems, due to dysfunction in the affected brain region or the pervasive effect of uncontrolled seizures and medications.

- An EEG may show localised epileptic activity. Structural pathology is sought using MRI.

Symptomatic generalised epilepsies

- These are usually severe seizure disorders affecting infants and young children in which uncontrolled generalised seizures are associated with generalised epileptic disturbances on EEG and global developmental delay or regression.

- Examples include West and Lennox–Gastaut syndromes. The characteristic seizures in these syndromes are epileptic spasms (clusters of brief tonic seizures that are usually generalised and in flexion), drop attacks and tonic–clonic seizures, generally difficult to control with medication.

Status epilepticus

See chapter 1, Medical emergencies.

Indications for commencing anticonvulsants

- After the first afebrile seizure, only 1/3 of children experience further episodes. Therefore treatment is not normally commenced unless there are features to suggest an increased risk of recurrence.

- Children with absence, myoclonic, complex partial seizures and epileptic spasms have usually had multiple seizures at presentation and require treatment.

- It is important to characterise the epileptic syndrome from history, EEG and sometimes imaging. This guides prognosis and the need for treatment.

- About 50% of childhood epilepsies have a favourable course from the outset, 25% gradually improve with time, and 25% are refractory to treatment.

The decision to investigate and treat a child following a seizure depends on many factors.

- Children with FC do not generally need EEG or imaging investigation.

- An EEG should generally be done in any child with a definite, non-febrile, seizure, whether generalised or partial. EEG aids in the characterisation of seizures and epilepsies, but should not be used to distinguish seizures from nonepileptic events.

- Brain imaging is reserved for children with epilepsy in whom there is suspicion from history, examination or EEG that there may be an underlying cerebral lesion. Children with typical forms of uncomplicated and well-controlled idiopathic focal or generalised epilepsy do not require imaging. MRI is more sensitive than CT scan in identifying cerebral lesions, particularly subtle abnormalities of the cerebral cortex.

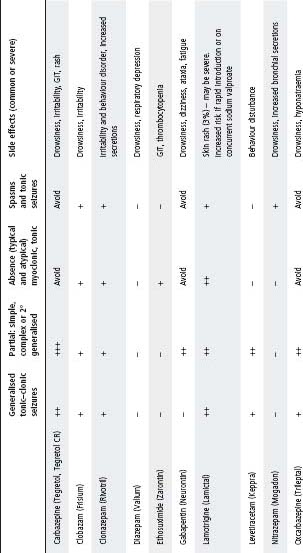

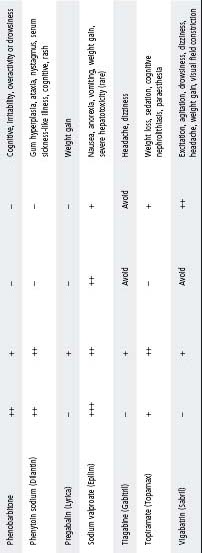

Antiepileptic medication is only indicated in children at risk of recurrent epileptic seizures (see Table 33.1).

Principles of anticonvulsant therapy

- Monotherapy: most patients are well controlled with one anticonvulsant.

- Titrate slowly: most antiepileptic medications are commenced at a low dose and titrated up to the maintenance dose, to avoid side effects during their introduction (‘start low and go slow’).

- Changing medications: introduce or change one anticonvulsant at a time, except in emergency situations.

- Dosage variation: individuals vary greatly in dosage requirements and tolerance. Young children and infants typically require relatively large doses.

- Monitoring: if seizure control is inadequate, or non-adherence or clinical toxicity is suspected, anticonvulsant blood levels may be measured for phenytoin, phenobarbitone, carbamazepine and valproate. Routine monitoring of phenytoin and phenobarbitone levels are indicated, especially in young infants and intellectually disabled older children in whom side effects may not be identified as easily. Other drugs are generally monitored with attention to usual prescribed doses and clinical markers.

- Poor response to medication: if seizure control is poor, the diagnosis and the choice of medication should be reviewed.

Depending on the type of epilepsy, one to several years free of seizures are generally required before anticonvulsants are withdrawn. This is done gradually over several months.

Parents also need to be instructed in the first aid management of seizures, and be given a plan for what to do when seizures recur. Safety precautions such as supervision in water and avoidance of heights need to be discussed. Driving and other lifestyle and vocational restrictions apply to older teenagers and adults with epilepsy.

Table 33.1 Guidelines for the use of common anticonvulsants

Notes:

- Table shows relative effectiveness of each drug against each of the major seizure types. It does not represent a comparison of one drug against another.

- Table represents suggestions only. Final decision of most appropriate anticonvulsant should take into consideration the patient’s age, neurological status, co-morbidities, epilepsy syndromes, EEG, patient and parent attitudes and potential side effects.

- Anticonvulsants listed as to ‘avoid’ can potentially exacerbate seizures.

- Sodium valproate should be used with caution in children <3 years old, particularly if multiple anticonvulsants are used and underlying cerebral pathology is present.

- Cognitive side effects are seen with all anticonvulsants (particularly benzodiazepines and barbiturates).

- For status epilepticus, refer to chapter 1, Medical emergencies.

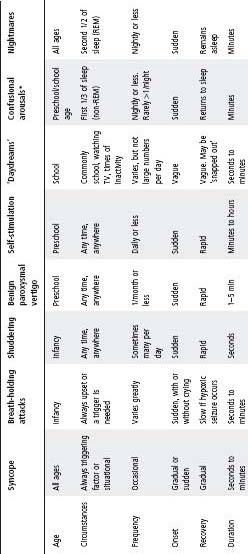

Non-epileptic paroxysmal events

- Many children referred for assessment of epilepsy do not have epilepsy, but rather a non-epileptic paroxysmal disorder such as syncope, breath-holding spells, parasomnias or non-epileptic staring.

- In differentiating epileptic from non-epileptic events, the description of the event is important, including the circumstances in which the event occurred and the details of what the child was doing immediately before the event.

- Most non-epileptic paroxysmal disorders can be diagnosed on history alone, or with the aid of a home video recording of a typical event. In some circumstances video-EEG monitoring may be required.

- The long Q–T syndrome should be considered in any episode of fainting or seizure that is not clearly due to typical breath-holding, vasovagal syncope or a definable epilepsy syndrome.

Table 33.2 lists some of these events and their salient features.

The acute onset of symmetrical limb weakness usually has a peripheral neuromuscular or spinal cord origin. Toxins (e.g. snake or tick bite), metabolic disturbance, systemic illness and psychogenic causes need to be considered under appropriate circumstances. Oral polio vaccine is a rare cause of acute flaccid paralysis.

Two key questions require urgent consideration:

- Is there a treatable cause?

- Is there respiratory or bulbar dysfunction of sufficient degree to warrant management in an intensive care unit?

Myasthenia gravis

- This diagnosis should be considered in any child with relatively acute-onset limb weakness, particularly if accompanied by ptosis, eye movement disorder, pharyngeal or respiratory insufficiency.

- A diagnostic/therapeutic trial of parenteral anticholinesterase is warranted if myasthenia is a possibility.

Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Presents with weakness (ascending progression may be less clear in young children), pain and sensory loss. Weakness may be misinterpreted as ataxia.

- The child should be transferred to a tertiary referral centre at the time of diagnosis, as respiratory weakness may occur rapidly

- Gamma-globulin or plasma exchange need to be commenced early if they are to be effective.

Table 33.2 Non-epileptic paroxysmal events

* Including sleep-walking and night terrors.

Infant botulism

- Suspect in children 2–9 months of age with constipation and rapid onset of weakness, particularly with ophthalmoplegia and bulbar/respiratory weakness.

- A child with suspected infant botulism should be transferred urgently to a centre capable of undertaking long-term ventilation.

Spinal cord compression

- Persistent or severe back pain and stiffness are ominous symptoms requiring prompt attention.

- Myelopathy should always be considered when there is paraparesis or quadriparesis without neurological dysfunction at higher levels.

- Brisk deep tendon reflexes or extensor plantar responses may not be prominent early and a sensory level is often the most important clue to a myelopathy.

- The confirmation or exclusion of trauma, tumour, abscess, haematoma or skeletal pathology is an urgent priority.

- Spinal imaging with MRI is required even when acute ‘transverse’ myelopathy is suspected.

- Steroid therapy is important in spinal cord compression, before decompression.

- Encephalopathies are characterised predominantly (but not exclusively) by cerebral hemispheric dysfunction producing at least two of the following:

– Altered conscious state.

– Altered cognitive state/personality.

– Seizures.

- The onset can be acute, subacute or chronic.

- Causes can be grouped into infective (or post-infective), hypoxic, traumatic, epileptic, metabolic, migrainous, raised intracranial pressure and drug or toxin exposure. The primary cause may be systemic or originate in the CNS (see also chapter 30, Infectious diseases, Encephalitis, p. 413).

Examination

Impaired conscious state or cognitive function is the cardinal sign. There may be widespread upper motor neurone signs. Meningism may or may not be present.

Investigations

Investigations are guided by history and examination. Consider the following:

- Electrolytes.

- Toxin and metabolic screen.

- Cerebrospinal fluid (microscopy and culture; viral and mycoplasma PCR).

Note: For contra-indications to lumbar puncture see chapter 3, Procedures.

- EEG.

- Neuroimaging: CT can exclude a mass lesion or acute bleed, but MRI is preferable in most circumstances. MRI of the brain and spinal cord may show multifocal demyelination in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM).

Management

- Early specialist referral – early neurosurgical referral if raised intracranial pressure is suspected.

- Seizure control.

- Identify and treat the primary cause.

- Consider empiric antimicrobials e.g. cefotaxime and aciclovir (see chapter 30, Infectious diseases).

- If ADEM is suspected, consider high-dose i.v. corticosteroids.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a monophasic inflammatory condition of the CNS that most commonly affects children and young adults. The usual presentation is with altered conscious state and multifocal neurological disturbance. It typically occurs following a viral prodrome and has been described following a variety of infections including measles, varicella, EBV, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and non-specific febrile illnesses.

Clinical

- A prodrome of ataxia before onset is typical.

- Encephalopathy: may vary in severity from irritability to coma.

- Multifocal neurological abnormalities such as ataxia, hemiparesis, optic neuritis, cranial nerve palsies and bladder dysfunction.

- A characteristic feature of ADEM is the evolution of symptoms and signs over time: new neurological symptoms and signs appear over the first few days (compared to other types of encephalitis where the onset is usually explosive without new manifestations after 24–48 h).

Investigation

MRI is the investigation of choice and usually demonstrates white matter changes (although grey matter involvement is not uncommon).

Management

General principles as above. Steroids are used in the treatment of ADEM despite the lack of controlled studies to prove their efficacy. Anecdotal evidence of their benefit is now strong. Steroid therapy may improve the patient’s condition but withdrawal of treatment while the disease is still active may result in the return of original symptoms, or the development of new symptoms.

Early studies found a mortality rate of up to 20% with a high incidence of neurological sequelae in those who survived. Recent case reports and small series suggest a more favourable prognosis, with most individuals recovering fully. Residual deficits in higher cognitive function may occur.

Chronic and recurrent headache

- Migraine is the most common identifiable cause of recurrent or chronic headache in childhood.

- In adolescence, muscle contraction (tension-type) headache is also common.

- Although rare, raised intracranial pressure and systemic illness must also be considered.

History

- Determine the location of the headache and its quality, duration, frequency and time of onset.

- Identify trigger factors (food, sleep deprivation), associated symptoms (e.g. nausea or vomiting, visual disturbance and localising or focal symptoms) and the disruption to normal activities.

- Inquire whether the symptoms are progressive and if there is a history of recent head injury; development of visual, gait or coordination difficulties; or changes in personality or intellectual functioning; or a family history of migraine or cerebral tumours.

- Take a detailed social history.

- Consider recording symptoms in a ‘headache diary’.

Distinguishing features

- Tension headache: tends to be persistent but usually does not interfere with sleep.

- Migraine: tends to have a fluctuating temporal pattern.

- Migraine without aura: usually frontotemporal or bilateral in older children. It is frequently accompanied by nausea and vomiting, followed by lethargy or sleep. Marked pallor is common and there is commonly a positive family history.

- Migraine with aura or prolonged neurological symptoms: uncommon in young children.

– Aura is not often reported by young children.

- Intracranial pathology: suggested by recurrent morning headaches; headaches that are intense, prolonged and incapacitating or that show a progressive change in character over time. Other features include abnormal examination findings, unusual migraine description and failure to respond to simple treatment measures. Such patients require urgent specialist referral.

Examination

- Do a thorough neurological examination, including examination of visual acuity and fields, eye movements, optic fundi, coordination and gait. Measure head circumference and blood pressure.

- Auscultate the skull for intracranial bruits; palpate over the sinuses, cervical spine and teeth.

- Assess the child’s growth and pubertal status; inspect the skin for neurocutaneous stigmata.

Management of migraine

- Reassure the child and parents that migraine is not usually a serious condition.

- In an acute attack, all that is usually required is trigger avoidance, stress management and the early use of paracetamol 15 mg/kg per dose orally, 4 hourly (max. 90 mg/kg per 24 h). NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen 2.5–10 mg/kg per dose (max. 600 mg) oral 6–8 hourly) can also be useful. The role of sumatriptan in childhood is not yet clear. In children with severe vomiting and oral agents are not tolerated, metoclopramide and chlorpromazine can be used.

- Prophylactic therapy for those with severe or frequent attacks is best used in consultation with a specialist. Propranolol or pizotifen are commonly used. Sodium valproate, cyproheptadine, verapamil, clonidine and amitriptyline can also be effective in some children.

- 2/3 of children cease having attacks but 50% of these have recurrences in adult life.

Craniosynostosis is an uncommon disorder of childhood affecting 4/10 000 children. It is a condition of premature fusion of the cranial sutures resulting in an abnormal head shape.

- The resulting head shape depends on which suture fuses. The common shapes are:

– Scaphocephaly (sagittal suture).

– Brachycephaly (coronal suture).

– Plagiocephaly (lambdoid suture). Most children with plagiocephaly have a postural deformation rather than craniosynostosis.

- The main problem is cosmetic. Only a small proportion have raised intracranial pressure.

Management

- Frank sutural synostosis requires surgical correction.

- Postural lambdoid plagiocephaly is not associated with sutural fusion and does not require surgery. It may partially correct spontaneously with changes in sleeping position. The asymmetric head shape becomes less obvious with hair growth.

Background

- Although considered rare by adult standards, childhood stroke is more common than brain tumours and amongst the top ten causes of death in childhood.

- Subtypes include arterial ischaemic stroke (AIS), cerebral sinovenous thrombosis (CSVT) and haemorrhagic stroke (HS).

- Mode of presentation, risk factors, aetiology, recurrence rates and outcome are dependent on stroke subtype and age.

- Neuroimaging is required to confirm the diagnosis and to differentiate from other paroxysmal neurological disorders.

Aetiology

- Arteriopathies – transient (e.g. post varicella, dissection) or progressive (e.g. Moya Moya disease) in AIS.

- Congenital heart disease in AIS and CSVT.

- Thrombophilias in AIS and CSVT.

- Head and neck/ENT infections in CSVT.

- Metabolic.

Clinical features

- Neonates: commonly present non-specifically with seizures, lethargy and apnoea. Focal neurological signs are rarely evident.

- Older infants: typically present with congenital hemiplegia, early hand preference and lateralised neurological deficits.

- Patients with CSVT: commonly present non-specifically with seizures and signs of raised intracranial pressure.

Diagnosis

- Urgent imaging:

– CT head – sufficient to exclude haemorrhage (but may potentially miss AIS or CSVT).

– MRI or MRA head – if not done immediately should be done <48 h.

- ECG and transthoracic echocardiogram:

– To look for structural heart defects and patent PFO with paradoxical embolisation.

- Prothrombotic work-up:

– Preferably taken before anticoagulation.

– Includes antithrombin, protein C, protein S, plasminogen, activated protein C resistance (APCR), prothrombin gene 20210A, anticardiolipin antibody (ACLA), lupus anticoagulant, serum homocysteine.

Management

General management

- Measures that improve outcome in adults include correction of fever, maintaining normal glycaemia, normal blood pressure.

- Oxygen – to keep SaO2 >95% through first 24 h.

- Close observations – initially hourly neurological observations.

- Keep nil by mouth until assessment by speech pathologist.

- If seizures, load with i.v. phenytoin (or phenobarbitone in neonates).

- Rehabilitation: early referral should be made once the child is stable.

Acute antiplatelet/anticoagulant treatment should be discussed with the neurologist and haematologist on call.

For neonates with AIS

- Aspirin or anticoagulation for 6–12 weeks is recommended for neonates with cardioembolic AIS.

- Do not use anticoagulation or aspirin for non-cardioembolic AIS unless there are recurrent events.

For children with AIS

- Initial treatment with aspirin, 1–5 mg/kg per day, unfractionated heparin (UFH) or lowmolecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for 5–7 days while being investigated for cardioembolic sources and vascular dissection.

- Treatment should be continued with LMWH or warfarin for another 3–6 months if dissection or cardioembolic source is confirmed.

- Conversion to aspirin, 1–5 mg/kg per day is recommended for all other children for a minimum of 2 years.

For children with CSVT

Anticoagulation is usually recommended, except if associated with a significant haemorrhage, patient is hypertensive or other risks for bleeding are present.

- For CSVT without significant intracranial haemorrhage:

– Initially with UFH or LMWH.

– Subsequently with LMWH or warfarin for a minimum of 3 months (neonates 6 weeks to 3 months).

- For CSVT with significant intracranial haemorrhage:

– Radiological monitoring at 5–7 days and anticoagulation if thrombus propagation occurs.

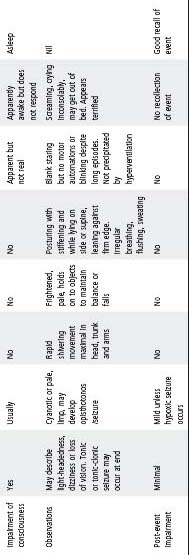

Assessment

- Determine the nature of the injury, its severity, the time of occurrence and the clinical course before the consultation.

- Always consider inflicted injury (child abuse) in infants and young children with head injury (see chapter 17, Child abuse).

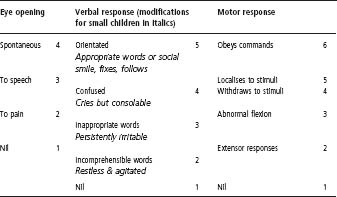

- Assessment using the Glasgow coma chart is essential (see Table 33.3).

- General and neurological examination findings will provide a baseline for further assessment and must be carefully recorded. In the unconscious patient the presence of brain stem signs must be assessed.

- In all but minor cases of head injury, cervical spine injury must be assumed until excluded.

Radiological examination

- A skull radiograph is not done routinely in patients presenting with a non-localised head injury and is not used to determine whether a child requires admission. If a child is assessed as being clinically unwell after a head injury, they should be transferred immediately to a centre with paediatric neurosurgical expertise; the transfer should not be delayed by the taking of a skull radiograph.

- If the child is unwell enough to warrant a skull radiograph, they should be in hospital under observation. There is no place for a skull radiograph ‘just in case’. The only exception is the child with a large scalp haematoma who is otherwise perfectly well, where a depressed skull fracture cannot be excluded clinically.

- A cervical spine radiograph is necessary when there is a suggestion that the spine may have been injured and in all patients with moderate to severe head injuries.

- A CT scan is indicated in all patients with significant head injury, particularly if there is the possibility of an intracranial haematoma, as suggested by severe headache and vomiting, a depressed conscious state or focal neurological signs.

- An MRI is indicated in those children in whom there is suspicion of a spinal cord injury or a vascular injury or anomaly.

Table 33.3 Level of consciousness – Glasgow coma scale

Blunt head injury

This form of injury is due to an impact on a flat surface that produces an acceleration– deceleration type of injury.

Effects

- Scalp haematomas: are common in the infant or young child. They may be responsible for a significant reduction in the circulating blood volume.

- Skull fracture: significant injuries may not necessarily have a skull fracture, but the majority do. Conversely, a skull fracture may not be associated with significant brain injury. The fracture is usually linear and it may extend to the skull base. The involvement of the nasal, paranasal or middle ear spaces implies that the injury is compound, with a risk of infection. Check for CSF rhinorrhoea or otorrhoea.

- Concussion: the most common and least serious type of traumatic brain injury. Involves transient loss of brain function, such as loss of awareness or memory of the event. The duration of unconsciousness is an indicator of the severity of the concussion.

- Localised brain damage: this is due to either local deformity at impact (which is not generally an important factor except for some injuries in infancy) or surface laceration of the brain due to brain movement within the skull.

- Intracranial haemorrhage: subarachnoid and subdural haemorrhages are usually due to a surface laceration of the brain. In extradural haemorrhage, a dural vessel is torn by distortion at or near the point of impact, especially if on the lateral aspect of the head.

- Intracerebral haemorrhage may result from local damage or a shearing injury within the brain.

Clinical course

Most patients rapidly recover from the effects of concussion in 12–24 h. A delay or reversal of recovery suggests haemorrhage, brain swelling, infection or an extracranial complication – most commonly an impairment of ventilation (hypercarbia → brain swelling).

Management

Mild

- A brief loss of consciousness (<5 min) without other neurological symptoms or signs suggests a mild injury and these patients can be sent home after an initial 4 h observation in emergency.

- Explanation and written information must be given to the parents regarding signs suggesting deterioration and indications for re-presentation (see below).

- The patient should be reviewed the following day, either by the local medical officer or in emergency.

Blows to the side of the head are potentially serious and these patients should be admitted.

Serious

A more serious head injury is indicated by:

- A longer period of unconsciousness.

- Increasingly severe headache with or without vomiting.

- A deterioration in the conscious state, behaviour or vital signs.

- Neurological defects.

- Bleeding or CSF leak from the nose or ear.

- Severe bleeding from a scalp wound.

- A superficial haematoma on the side of the head. This may be associated with an extradural haematoma, even if no fracture is seen on the radiograph.

Children with these signs will require admission and must be observed carefully for at least 48 h.

Delayed presentation

This can be grouped into four categories:

- Clinical features of potentially serious head injuries – admit.

- Patients with a wide linear fracture and a large scalp haematoma – admit.

- Patients with a skull radiograph showing a narrow linear fracture, but who do not require admission on clinical grounds – discuss with a neurosurgeon and consider early involvement of a paediatrician.

- Apparently well patients – send home after appropriate advice, with instructions to return immediately if there is any deterioration.

Localised head injury

In these injuries the damage is predominantly confined to a focal area of the head. Injuries of this type are relatively more common in children than in adults.

Effects

- Simple or compound depressed fractures are common.

- Infection may occur with compound injuries.

- Focal contusion or laceration of the brain may be present to a varying size or depth, and may produce neurological signs or seizures.

- Concussion may be absent.

Management

- Radiographs are always required and should be done as part of the admission including, where indicated, tangential views. CT is indicated in focal injuries.

- Admission for neurosurgical assessment and monitoring is required in most cases.

- To prevent wound infection all patients with external compound head injuries should receive antibiotics (flucloxacillin i.v., with contamination add gentamicin i.v. and metronidazole i.v.) and the wound covered by a head dressing. Prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated, however, for patients with internal compound fractures (base of skull) with CSF leaks. These patients should be observed closely and, if they develop a fever with no obvious focus, given empirical antibiotics (e.g. flucloxacillin 50 mg/kg (max. 2 g) i.v. 4–6 hourly and cefotaxime 50 mg/kg (max. 2 g) i.v. 6 hourly).

Box 33.1 Minor head injuries: discharge instructions for parents

For the next 24 hours keep a careful watch over the patient, who should be roused at least every 2 hours. The child must be reassessed immediately if you notice any of the following:

- The child becomes unconscious or more difficult to rouse.

- The child becomes confused, irrational or delirious.

- There are convulsions or spasms of the face and limbs.

- The child complains of persistent headache or has neck stiffness.

- Repeated vomiting.

- Bleeding from the ear or recurrent watery discharge from the ear or nose.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree