Routine care

The vast majority of deliveries are uncomplicated and do not require medical intervention. The baby will start breathing spontaneously and will be kept adequately warm by being swaddled and cuddled by the mother. Early contact helps with establishing bonding and breast-feeding.

The first minutes

Establishing breathing

The major stimuli to start breathing include cooling of the face and physical stimuli as well as hypoxia and acidosis. Babies usually start breathing within seconds of birth. If the baby is not breathing, drying with a towel is a very effective stimulus.

Heat loss after birth

Evaporative cooling occurs very quickly after birth. It is minimised by drying and wrapping the baby in warm towels. A well, term infant will be kept warm by being swaddled and cuddled by the mother. The baby’s rectal temperature should stabilise around 37 °C (±0.3 °C) by 1 h of age. A baby who becomes cold may need controlled warming under a radiant heater or in an incubator and should always be assessed for illness. Both hypothermia and hyperthermia are bad for babies.

The umbilical cord

This is clamped and cut cleanly close to the skin just after birth. The cut end and the base of the cord must be kept clean and dry. Antiseptic solution, such as chlorhexidine in alcohol, may be applied daily until the cord stump drops off. Omphalitis may occur if this is not done. The plastic clamp can be removed after 2 days.

The first hours

After the infant’s temperature is stable, s/he can be washed with soap and water. There is no hurry to do this. Record the heart rate, colour, respiratory rate and effort, at frequent intervals, depending on the infant’s condition.

Often the baby will be very alert and breast-feeds should be started at these times.

Vitamin K

All infants, regardless of size, maturity, or ill health, should receive vitamin K mixed micelles (Konakion) 0.1 mL i.m. This eradicates haemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Claims associating i.m. vitamin K and childhood cancer have not been substantiated. An increased incidence of both early and late haemorrhagic disease of the newborn occurs in breast-fed infants who received either an oral or inadequate i.m. dose, or no prophylactic vitamin K. Parents who insist on their infant having oral vitamin K must be given instructions that it must be given for three doses at 2-weekly intervals from birth.

The first day

After an initial period of alertness the infant will sleep for long periods and may not be too demanding with feeds. However, the infant must:

- Suck and swallow easily: if s/he does not, consider unrecognised prematurity, a congenital abnormality, hypoglycaemia or infection.

- Pass urine: many babies pass urine at birth and it is missed. If a boy does not pass urine in the first 24 h, consider posterior urethral valves. This requires careful urological investigation. A reasonable screening test is to ultrasound the bladder and see if it empties completely with micturition.

- Pass meconium within the first 48 h: if not, consider bowel obstruction or Hirschsprung disease.

The first examination

The purpose of this examination is to detect congenital abnormalities, reassure the parents and to discuss their concerns. Many major abnormalities will have been seen on antenatal ultrasound, but not all.

- Observation: before disturbing the baby observe the posture, behaviour, general appearance, colour and well-being.

- Chest: while the baby is quiet examine the heart sounds, rate, presence of femoral pulses and the pulse characteristics. Many babies have a very soft murmur in the first few days. If it sounds pathological, is associated with other signs or persists, then refer to a cardiologist. Normal babies breathe so shallowly when they are sleeping that it can be difficult to see. Recession and laboured breathing are the most important signs of respiratory distress. In babies the rate and depth of each breath can be very variable.

- Head and neck: look for scalp defects; fractures; haematomas; lacerations; eye size, anatomy and red reflex; neck cysts, lumps or fistulae; cleft palate; tongue size and shape; ear position, shape, size and tags or fistulae and facial symmetry when crying. A cephalohaematoma is a soft boggy swelling over one bone (usually the parietal) due to blood under the periosteum. It needs no treatment. Beware of a generalised boggy swelling all over the scalp in a shocked baby. It may be a subgaleal haemorrhage. Babies can bleed profusely into these and they are a neonatal emergency.

- Abdomen: feel for masses (liver, spleen, kidneys, bladder and ovaries), distension and tenderness. Examine the genitalia, anus and inguinal and umbilical region for herniae. The umbilicus should be clean and dry. The liver is often just palpable or percussible in normal babies.

- Limbs: examine for abnormal fingers, hands, toes and feet; posture of the hands and feet; and the flexibility of the joints.

- Hips: carefully examine for congenital dislocation by observation and specific palpation (see chapter 34, Orthopaedic conditions).

- Measurement: naked weight, length and head circumference should be recorded and plotted on the growth chart in the baby’s record book.

The first week

- Feeding: will be established during this time. After an initial phase of waking frequently until lactation is established, the breast-fed baby should establish a regular cycle of waking for feeds, followed mostly by sleeping. However, even in the first week of life, some babies will stay awake after some feeds. Some babies will sleep for 4 h; others will wake frequently for small feeds. After an initial weight loss of up to 10% over the first few days, the baby’s weight should stabilise and then increase towards the end of the first week.

- Stools: change over the first 4–5 days from black, sticky meconium, to dark-green, yellow-green and finally to loose yellow once full breast-feeding is established. The frequency of bowel actions varies, but is usually once per feed after feeding is established.

- Urine: production is usually low in the first few days, but increases after feeding has been established, with a urinary frequency of usually at least once per feed.

- Jaundice: occurs in >50% of babies after the first 24 h of age; see p. 438.

- Screening: is done on the third day for cystic fibrosis, hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, and other metabolic conditions from a heel prick. Results are available approximately 1 week after sampling. Negative (normal) results are not notified, but the laboratory will contact the baby’s doctor regarding the management of children with positive (abnormal) results and advise on appropriate management. This usually involves an immediate referral to a tertiary paediatric hospital for further testing and treatment.

Behaviour and sleep

In the first days, babies mostly sleep and eat. They spend little time awake when not feeding, unless inadequate milk supply leads to hunger. Their sleep cycles through quiet and active phases and may switch from one type of sleep to the other every 5–10 min. In quiet sleep babies appear to sleep deeply, breathe quietly and regularly and do not move much. They often appear quite pale in this phase of sleep and their limbs are cool to touch. Parents occasionally mistake this appearance for apnoea. In active sleep (rapid eye movement [REM] sleep), they breathe erratically, make various noises (including crying, vocalising and yawning), have many body movements and may seem to be waking up. It is in this phase of sleep that babies frequently have short periods (up to 10 s) of apnoea. This behaviour is normal but can be confusing and frightening to parents.

The first month

The baby should be weighed and measured weekly to ensure adequate nutrition. The results must be recorded and plotted on growth charts. Weight gain for term babies varies from 150–250 g per week.

Maternal concerns about the baby usually relate to crying, not sleeping enough, not gaining weight, rashes or poor feeding. (See chapter 6, Nutrition; chapter 11, Common behavioural and developmental problems; and chapter 12, Sleep problems.)

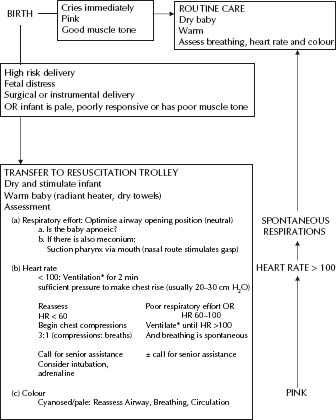

Fig. 32.1 Neonatal resuscitation. (Adapted from the Australian Resuscitation Council Neonatal Guidelines, Section 13, February 2006.) See also Neonatal Handbook website http://www.rch.org.au/nets/handbook

- Increasingly it has been recognised that the traditional practice of resuscitation with 100% oxygen may not be beneficial and a systematic review demonstrates that resuscitation with air, rather than oxygen, reduces perinatal mortality. It should be noted that ‘normal’ oxygen saturations in the preterm infant are as low as 40% for the first 4 min of life, with those in the term infant ranging from 60% at 1 minute to 90% at 5 min, without intervention with supplemental oxygen. Currently, resuscitation with 100% oxygen, or medical air, is acceptable.

- The most common cause for failure of resuscitation is inadequate ventilation. This can be due to a poor seal at the facemask or inadequate pressure. Sometimes pressures up to 50 cm H2O are required for the first few breaths.

- A baby who does not respond and has a slow heart rate (<60 bpm) needs cardiac massage and may need infusions of bicarbonate, blood or adrenaline to improve cardiac output depending on the underlying problem. Chest compressions should be provided with positive pressure ventilation in a ratio of 3 : 1.

- In general, admission to a neonatal intensive care unit is required if spontaneous ventilation is not established by 5 min of age.

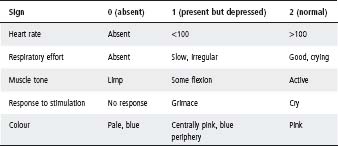

- The Apgar score is used to assess the condition of the baby at 1, 5 and occasionally 10 min of age (see Table 32.2). The total score ranges from 0 to 10. A score between 7 and 10 indicates the infant is well. A score between 4 and 7 indicates the baby needs assistance. A score between 0 and 3 indicates severe cardiorespiratory depression. In practice it is best to describe exactly what was happening to the infant.

- Naloxone is rarely required. It should only be given if a mother has received narcotics within 2 h of delivery. When using naloxone, be aware that the effect can wear off quickly and the baby may then develop apnoea, the most serious sign of narcotic overdose. Do not use naloxone if there is a possibility of maternal narcotic abuse (risk of fulminant withdrawal in the baby).

When the baby is fully examined, normal variants or minor problems are often noted. If they are obvious to the doctor, most will be obvious to the parents who often need explanation and reassurance.

Table 32.1 Endotracheal tubes

| Weight | ETT size | Tie at lips |

| <1000 g | 2.5 mm | 6.5–7.0 cm |

| 1000–2000 g | 3.0 mm | 7–8 cm |

| 2000–3000 g | 3.0/3.5 mm | 87#8211;9 cm |

| >3000 g | 3.5/4.0 mm | >9 cm |

Table 32.2 The Apgar score

Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Oct, 1994, 94: 558–565.

Skin

- Naevus flammeus (‘stork–bite’): dilated capillaries, on the nape of the neck and on the bridge of the nose, eyelids and adjacent forehead. They fade over 6–12 months.

- Milia: small white blocked sebaceous glands on the nose. They disappear over the first month.

- Miliaria: there are two types – ‘crystallina’ and ‘rubra’. Miliaria crystallina are beads of sweat trapped under the epidermis and are most prominent on the forehead in babies who are overheated. Miliaria rubra, also called ‘heat rash’, usually appear after a few weeks of age, fluctuate over 2–3 weeks and then disappear. They are related to an increasing activity of the sweat glands. They are prominent on the face, in babies who are overheated.

- Erythema toxicum (‘toxic erythema’ or ‘urticaria of the newborn’): these are red ‘urticarial’ spots over the baby’s trunk that peak at 2–3 days of age and generally resolve by the first week of life, but occasionally runs a fluctuating course over a few weeks. They are harmless and of unknown cause. New lesions have a broad erythematous base up to 2–3 cm diameter with a 1–2 mm papule or pustule. The diagnosis can be made with confidence on clinical appearance alone. The differential diagnosis is staphylococcal skin infection, which is persistent and purulent. An examination of the fluid reveals neutrophils and Gram-positive cocci in infection, or eosinophils and no organisms in erythema toxicum.

- ‘Mongolian’ blue spot: this condition results in areas of increased melanin deposition over the lower back and sacrum. It can be more extensive and is sometimes mistaken for bruising. It is present in most babies born to dark-skinned parents. It gradually lightens over a few years, as the rest of the skin becomes more pigmented.

- Dry skin: babies who are post-term have a thicker epidermis and hence drier-looking skin after birth. This dry skin may occasionally crack and bleed around the hands and feet during the first few days. Emollients will help. Otherwise the dry skin should be allowed to peel off naturally, which may take up to 1–2 months.

Deformities

- Moulding: the skull moulds to enable the head to be delivered. This changes to a normal shape over the first few days. In addition there may be postural deformities of the face, skull and limbs that are related to the baby’s position in the uterus. These gradually improve after birth, but sometimes they do not disappear completely – very few people are symmetrical, especially in their face.

- Positional talipes: is quite common. The foot is deformed from being compressed in the uterus. To determine whether this is pathological, test the range of movements of the foot. A normal foot can be flexed and extended so that the angle with the shin is less or more than 90°. The forefoot should be mobile. A fixed deformity should be referred to a paediatric orthopaedic surgeon for management (see chapter 34, Orthopaedic conditions).

Other

- Puffy eyelids/scalp oedema: the newborn infant has excess body fluid at birth. Fluid accumulates easily in the eyelids and, after lying on one side, the lower eye may be more swollen. Scalp oedema is common in the first few hours after a normal birth, but can persist for several days. This needs further investigation if it persists, or is generalised.

- Bruising/petechiae/subconjunctival haemorrhages: the part of the baby that was presenting during delivery is commonly bruised. If the cord was wrapped tightly around the neck, the baby may have petechial haemorrhages on the face and head (traumatic cyanosis). Subconjunctival haemorrhages occur in up to 25% of babies delivered normally and do not adversely affect vision. They may persist for up to 2 weeks and must not be confused with postnatal trauma. Bruising is common after forceps deliveries, particularly over bony prominences, but disappears over the first week of life. Less commonly after forceps deliveries, firm nodules may be noted in the subcutaneous tissue over similar sites. This is subcutaneous fat necrosis and resolves spontaneously over the first month of life.

- Sucking blisters: these are common on the lips, particularly the upper lip and need no treatment.

- Epstein’s pearls: these are small white cysts on the hard palate in the midline. They are benign and disappear in the first weeks after birth.

- Breast hyperplasia: a breast bud is palpable in most term babies, regardless of gender. The breasts may become enlarged during the first week and milk may be observed. They should be left alone and the swelling will subside over several months. However, a breast that is swollen, hot, red and tender may be infected.

- Hiccups: these occur frequently after a feed. They are not caused by inadequate burping and are harmless.

- Snuffles: these occur in about 1/3 of normal babies in the few weeks after birth. Despite the noise, the baby is otherwise quite well and is able to feed normally. The problem diminishes with time as the baby’s feeding becomes more efficient and the nasal passages enlarge. It is only important if it interferes with the baby’s ability to suck.

- Vomiting: small vomits are harmless. The serious signs are vomit that is bile-stained (grass green), blood-stained, projectile, persistent or associated with frequent choking or failure to thrive. Bile-stained vomiting must be referred to a tertiary paediatric centre for an upper barium study.

- Bleeding umbilical cord: small amounts of bleeding occur rarely as the cord is separating and require no treatment. More profuse bleeding may indicate a bleeding disorder.

- Umbilical hernia: this is present in approximately 25% of babies and resolves in almost all. Consider surgical referral if present beyond 2 years.

- Vaginal skin tag: a small tag of vaginal skin commonly protrudes between the labia in newborn girls. It is benign and disappears as the labia enlarge.

- Vaginal discharge: a small amount of vaginal mucus is universal. In some it can be bloodstained during the first week as the endometrium involutes.

- Red urine: a red-orange discoloration of the napkin when the urine is concentrated (common in the first few days of life) may be mistaken for blood, but is usually due to urates.

- Clicky hips: some ligamentous clicking is common in all large joints, including the hips. It can be considered normal in the absence of any abnormal movement of the femoral head, restriction of hip movement, strong family history, or breech presentation. However, if there is any doubt, hip ultrasound is indicated.

Jaundice is common in the newborn period and is almost always caused by unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia. The clinical importance of jaundice depends on the time at which it is observed and the gestational age of the baby. Jaundice needs to be taken seriously; if the bilirubin level is too high (>340 μmol/L) brain damage (kernicterus) may occur.

The first 24 hours

- Jaundice in the first 24 h is abnormal. The infant must be admitted to a special care nursery and investigated urgently.

- It is mostly caused by haemolysis, usually ABO or rhesus incompatibility between mother and fetus. Severe haemolysis leads to a rapid rise in serum bilirubin over a few hours.

- The following investigations are required urgently: the mother’s and baby’s blood group, the baby’s serum bilirubin (total and unconjugated), direct Coombs’ test, haemoglobin, white cell count, and platelets. The mother’s red cell antibodies may need to be tested.

- Further investigations are needed if there is no haemolysis, or conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia is present.

- Phototherapy should be commenced if the bilirubin level is >150 μmol/L in the first 24 h in a term infant.

- An immediate exchange transfusion may be required if the jaundice is due to rhesus incompatibility and the infant is anaemic (Hb < 110 g/L). This primarily corrects the anaemia and removes antibodies. Further exchange transfusions may be required to control the jaundice.

- Frequent monitoring of bilirubin levels is essential as rapid changes may occur. The results should be plotted on a chart and an ‘action level’ for exchange transfusion established so that mistakes are not made.

Days 2–7

Jaundice is considered to be ‘physiological’ if the following criteria are satisfied:

- The jaundice appeared on day 2–4.

- The baby is not premature.

- The baby is well (afebrile, feeding well and alert).

- The baby is passing normal-coloured stools and urine.

- There are no other abnormalities.

- Bilirubin levels are not above treatment threshold.

About 1/3 of term babies become visibly jaundiced by 2–4 days of age. Jaundice is visible once serum bilirubin is >85–120 μmol/L. In physiological jaundice, serum bilirubin rarely exceeds 220 μmol/L. If the unconjugated bilirubin is >220 μmol/L, other causes, including infection, should be considered.

Well, term infants with no haemolysis are at minimal risk of kernicterus. Infants who are at higher risk of kernicterus are:

- Unwell infants (particularly those exposed to hypoxic insults).

- Infants with haemolysis.

- Preterm infants.

These infants should have treatment started at lower bilirubin levels. For guidelines in management of jaundice, see Tables 32.3, 32.4 and 32.5.

In most places, a centralised tertiary neonatology service is available to give phone advice and coordinate retrievals. Paediatricians seeking advice about issues such as exchange transfusions are encouraged to contact their local service.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree