Assessment

A high index of suspicion is the primary rule in the diagnostic approach to metabolic disorders.

The presenting symptoms of metabolic diseases are non-specific (see Table 31.1). Children presenting in extremis must be resuscitated quickly, but with attention to procuring blood samples before administration of drugs/fluids. Discuss with a senior. See chapter 1, Medical emergencies.

History must be thorough and include:

- The pregnancy, delivery, neonatal period, dietary history (food refusal or craving), medications, and motor and cognitive development.

- The family history, with particular note of consanguinity, relatives with seemingly unrelated disorders (e.g. ‘retardation’), maternal morbidity during pregnancy (e.g. severe chronic vomiting, liver disease and intercurrent infections), miscarriages, unexplained deaths of newborns and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), as well as other children having similar clinical signs in the family.

- Physical examination: some findings may be suggestive of a metabolic disease. These are summarised in Table 31.2.

Blood, urine and CSF samples collected at the time of presentation may be diagnostic and are invaluable. Always attempt to collect these samples before commencing treatment, but do not delay treatment in crisis situations.

Table 31.1 Clinical features suggestive of a metabolic disease

| Age | Clinical signs | Possible diagnosis |

| Day 1 of life | Seizures | Persistent hyperinsulinaemia |

| Mitochondrial cytopathy | ||

| Disorders of purines and pyrimidines | ||

| Neonatal period* | Vomiting, feed refusal, changes in respiration, prolonged jaundice, lethargy or irritability, movement disorder, seizures, hypo/hypertonia, changes in the level of consciousness | Organic acidaemias, Non-ketotic-hyperglycinaemia Urea cycle defects Fatty acid oxidation defects Galactosaemia Mitochondrial cytopathy Disorders of purines and pyrimidines |

| 1st year of life | Same as above, plus: Failure to thrive, motor/cognitive developmental delay or regression | Organic acidaemias Urea cycle defects Fatty acid oxidation defects Lysosomal storage diseases |

| Early childhood | Mental retardation, seizures, behavioural abnormalities, learning diffi culties, autistic features | Organic acidaemias Urea cycle defects Fatty acid oxidation defects Amino-acidopathies Lysosomal storage diseases Adrenoleucodystrophy |

| Any age group** | Acute decompensation: change in consciousness, seizures, movement disorder, change in respiration | Organic acidaemias Urea cycle defects Fatty acid oxidation defects Adrenal insuffi ciency |

* Symptoms should be considered in relation to the child’s age (in days), fasting, food intake (i.e. specific sugars, protein and fat) and changes in diet.

** May follow an intercurrent infection, prolonged fasting, a large meal with high protein content, and so on.

There are four initial questions to be answered:

- Is there acidosis, and is it of metabolic origin?

- Is there hypoglycaemia?

- Is there hyper-or hypoketonaemia?

- Is there hyperammonaemia?

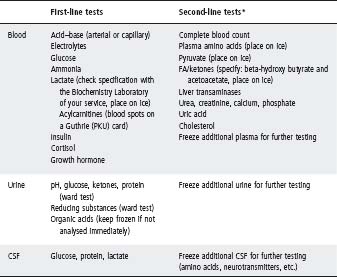

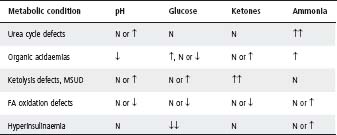

The tests listed in Table 31.3 should be done to answer these questions. See Table 31.4 for interpretation of laboratory results.

In addition to these tests, brain CT or MRI (looking for brain oedema) and abdominal Doppler ultrasonographic examination (looking for porto-caval shunting as a cause of hyperammonaemia) may be helpful in the diagnostic process.

Table 31.2 Physical examination: potential signs of metabolic disease

| General appearance | Growth parameters: height and weight |

| Dysmorphism | |

| Skin | Rash |

| Odour | |

| Hyperkeratosis | |

| Pigmentation | |

| Signs of chronic scratching | |

| Head and neck | Craniomegaly |

| Dysmorphism | |

| Bulging fontanelle | |

| Clefts (mid-line defects) | |

| Signs of rickets | |

| Abnormal eye movement | |

| Chest | Signs of lung disease |

| Heart | Cardiomegaly |

| Signs of cardiac failure | |

| Abdomen | Hepato ± splenomegaly |

| Signs of liver disease | |

| Genitalia | Ambiguous genitalia |

| Skeleton | Signs of rickets |

| Bone or joint pain, contractures | |

| Abnormal spine posturing/vertebral disease | |

| Muscles | Muscle mass, wasting |

| Neurological | Muscle strength, tone |

| Sensation | |

| Reflexes (tendon and primitive) | |

| Movement disorders | |

| Ataxia |

Table 31.3 Investigation of suspected metabolic disease

Table 31.4 Interpretation of laboratory results

FA, fatty acid; MSUD, maple syrup urine disease; N, normal.

Definition

A blood sugar level of <2.5 mmol/L. If suspected clinically and on a glucometer, it must be confirmed with a true blood glucose measurement in the laboratory.

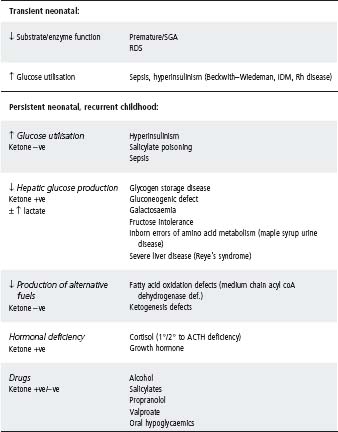

Causes

See Table 31.5. The two most common causes of hypoglycaemia beyond the neonatal period are:

- Hyperinsulinism in the first 2 years. This usually results in persistent, severe hypoglycaemia and may lead to permanent brain damage, as the brain depends on glucose in the first 2–3 years of life. Urinalysis for ketones is negative. Treat with glucose at >10 mg/kg per min.

- ‘Ketotic hypoglycaemia’ (or ‘accelerated starvation’): the cause is unclear, and this entity may simply be one end of the normal spectrum or reaction to fasting

– Usually >2 years old.

– Often small for age, ± past history of small for gestational age.

– Poor oral intake in 24 hours prior to hypoglycaemia.

– Documented hypoglycaemia.

– Early morning seizure.

– Spontaneous remission by 8 years.

– Exclude hypopituitarism or adrenal insufficiency.

Specific signs and symptoms

Infantile/neonatal

- Apnoea/tachypnoea/cyanotic spell.

- Hypotonia, poor crying and feeding.

- Irritability, tremor and seizures.

Childhood

- Catecholamine mediated: hunger, pallor, sweating, tremor and tachycardia.

- Neuroglycopenic effects: altered conscious state, abnormal behaviour, seizure.

Relevant history

- Gestation and birthweight.

- Previous episodes.

- Relationship to meals/feeds and duration of fasting.

- Age at onset of hypoglycaemia.

- Family history of neonatal deaths and affected relatives.

- Drugs – alcohol and insulin.

- Intercurrent illness.

Specific examination features

- Growth parameters (height, weight and head circumference). Overgrowth may suggest hyperinsulinism; underweight ketotic hypoglycaemia.

- Midline defects (e.g. cleft lip, central incisor and micropenis) may suggest hypopituitarism.

- Muscle bulk, power and tone (glycogen storage disease).

- Hepatomegaly (e.g. glycogen storage disease and galactosaemia).

- Jaundice (e.g. galactosaemia, citrullinaemia type 2).

- Cataracts (e.g. galactosaemia).

- Unusual odours (e.g. ketones and maple syrup) suggesting metabolic disease.

- Ambiguous genitalia (congenital adrenal hyperplasia with adrenal crisis).

Table 31.5 Causes of neonatal/childhood hypoglycaemia

IDM, infant of a diabetic mother; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome; SGA, small for gestational age.

Investigation

Before i.v. glucose is given (and usually before the true blood glucose is available), blood and urinary samples at the time of hypoglycaemia must be obtained as these are essential for diagnosis. See Table 31.3 for first-line tests to be done.

Some hospitals have sets of the required tubes, labelled ‘Hypoglycaemia Kit’, but if not have a staff member look up the tubes required, while you are cannulating, collecting samples and treating the hypoglycaemia. Specimens should be taken and returned on wet ice as soon as possible to the laboratory.

Do not discard any blood or urine taken at time of hypoglycaemia – send any excess to the laboratory marked ‘excess – store’.

Management

- Neonate: i.v. 200–300 mg (2–3 mL/kg of 10% dextrose) over 5 min, then 5–10 mg/kg per min.

Note: 10% dextrose solution at 0.1 mL/kg per min will supply 10 mg/kg per min.

- Older children: i.v. 200 mg (1 mL/kg of 20% dextrose) over 5 min, then 3–5 mg/kg per min until stable.

Always discuss with metabolic physician.

There are three basic guidelines in the treatment of metabolic conditions:

- Enhance the disposal of the accumulating toxic metabolites. Adequate fluid intake is important, particularly as many of the toxic metabolites are excreted by the kidney. Correct dehydration and replace ongoing losses (diarrhoea, fever, etc.). Haemofiltration should be considered in severe cases or when there are indications of rapid accumulation of toxic metabolites (rapid deterioration in the level of consciousness, increasing intracranial pressure, etc.).

- Avoid catabolism, which can lead to an ongoing accumulation of these metabolites. It is of the utmost importance to provide the patient with an adequate amount of calories for age and weight. I.v. glucose infusion (10–20% solution) is usually a safe mode of treatment. I.v. fat solutions (Intralipid, 10 or 20% solutions) may serve as a good source of calories in a small fluid volume. Do not use i.v. fat solutions if you suspect a fatty acid oxidation disorder. I.v. amino acids can usually be given at a low dose (e.g. 0.5 g/kg per day for a newborn) to enhance anabolism, unless there is hyperammonaemia.

- Enhance enzymatic activity, whenever possible. Treatment with some vitamins and cofactors may be indicated to enhance the disposal of toxic metabolites or to enhance residual enzymatic activity. These are listed in Table 31.6. Treatment with carnitine and biotin is considered ‘rescue treatment’. These should be used even if the diagnosis is unknown, following proper blood, urine and, if indicated, CSF sampling. Consult with the metabolic physician.

Table 31.6 Treatment with vitamins and other supplements (rescue treatment in bold)

| Compound | Dose | Indication |

| Carnitine | 100–300 mg/kg per day (oral) | Organic acidaemias |

| 15–60 mg/kg per day (i.v.) | Fatty acid oxidation disorders | |

| Thiamine (B1) | 100–300 mg per day (i.v. or oral) | MSUD, PDH deficiency |

| MRC disorders | ||

| Riboflavin (B2) | 100–300 mg/day | Glutaric acidurias |

| MRC disorders | ||

| Pyridoxine (B6) | 100–300 mg/day (i.v. or oral) | Homocystinuria |

| Seizures | ||

| Cobalamin (B12) | 1 mg/day as hydroxycobalamin (i.m.) | Homocystinuria and MMA, combined or separately |

| Biotin | 10–20 mg/day (i.v. or oral) | Hyper-lactataemia Biotinidase deficiency Holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency |

| Vitamin C | 250 or 500 mg/day or 100 mg/kg per day (oral) | MRC disorders Organic acidaemias |

| Vitamin K (menadione) | 10 mg/day (oral) or 1 mg/day i.m. | MRC disorders |

| Coenzyme Q | 50–300 mg/day | MRC disorders |

| Folic acid | 5 mg/day | MRC disorders with anaemia Some amino-acidopathies |

| Folinic acid | 5–7.5 mg/day | Bioamine-neurotransmitter defects |

| Glycine | 200 mg/kg per day | May be given in some cases instead of carnitine |

MMA, methylmalonic aciduria; MRC, mitochondrial respiratory chain; MSUD, maple syrup urine disease; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase.

Urgent autopsy for suspected metabolic disease

- Collect samples as soon as possible after death, preferably within 2 h.

- Note the time between death and freezing or the attainment of the samples.

- Obtain blood, urine, CSF and bile samples, if possible (see Table 31.3), for further metabolic analysis. A vitreous humour specimen should be obtained if urine is unavailable.

- Obtain a skin biopsy for fibroblast culture. One piece of full-thickness skin (2–3 mm surface diameter) in a tissue culture medium bottle, or a viral medium bottle or sterile normal saline without preservatives. Store in a refrigerator at 4 °C. Do not freeze this sample.

- Organ biopsies for light microscopy should be placed in aluminium foil or Parafilm®, frozen immediately (on dry ice) and put in screw-cap tubes. Store in a freezer at −70 °C. Note the time of sampling.

- Organ biopsies for electron microscopy should be placed in a glutaraldehyde bottle. Store in a refrigerator at 4 °C. Do not freeze this sample.

- Muscle samples are preferably from the quadriceps. If the parents object to the two incisions (the muscle and liver), suggest a right upper quadrant incision to take samples from the liver, rectus muscle and skin biopsy.

- Blood for DNA tests: 10 mL of heparinised blood (no mixing beads or separating gel) can be sent at room temperature if they are expected in the laboratory within 24 h, or frozen.

Note: To avoid mistakes in obtaining and handling of samples please consult with the metabolic physician to your service.

USEFUL RESOURCES

- www.rch.org.au/nets/handbook – Follow the link to Metabolic Diseases.

- http://emedicine.com/emerg/topic768.htm – Summary article of inborn errors of metabolism.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree