A paediatric example

A Consultant Paediatrician appeared before the Fitness to Practise Panel facing allegations about his management of a sick child four years earlier. This child had the rare condition of Diamond Blackfan Anaemia. In anticipation of a bone marrow transplant, she had been prescribed Ferriprox. Five months after she began this treatment, she suffered a febrile convulsion and collapsed. She was admitted to hospital at 8 p.m., where she was looked after by a Registrar. At 3 a.m. the Registrar telephoned the consultant at his home for advice on the child’s management. It was alleged that the Consultant’s advice to the Registrar was not sufficiently clear and specific, particularly in relation to whether in a neutropenic patient, the antibiotics, Tazocin and Gentamicin should be administered.

The Panel weighed up the oral evidence of both the Registrar and the Consultant. It took into account variations between the Consultant’s oral evidence to the Panel and his written evidence to a hospital investigation four years before, shortly after the child died. The Panel decided that he did not give clear advice to the Registrar, with the result that the antibiotics were not administered for another two to three hours.

The Panel heard evidence from a number of experts about the significance of this delay. One expert told the Panel it was reasonable to allow a breathing space in order to take stock and consider the right way forward. Another expert said that antibiotics should have been given as soon as possible after the neutropenia was documented. The Panel agreed with this view and concluded that the delay incurred by the Consultant’s lack of clear instructions to the Registrar was not in the patient’s best interests.

The Consultant went to see the child for himself at the hospital at 6.30 a.m. He made a written plan for her management, but it was alleged and found proved that that plan failed to provide for close monitoring by the nurses, frequent reviews by the doctors, and clinical observations every 30 minutes. The Panel referred to the fact that a shift change was due at 8 a.m. but that, having made his plan, the Consultant then left the hospital without adequately communicating it. The Panel said the Consultant should have ensured that the staff were fully aware of the seriousness of the child’s condition. He should have issued a clear and emphatic plan for the frequent and close monitoring of the child’s vital signs, describing what action to take if her condition deteriorated.

Having made these findings, the Panel then considered whether they amounted to misconduct and whether the Consultant’s fitness to practise was impaired. They found that his acts and omissions were indeed misconduct.

However, on the question of impairment, the Consultant produced evidence of his remediation since the episode. He gave the Panel a copy of his Personal Development Plan, his CPD record, his 360° appraisal and a bundle of testimonial letters. After the events, the Consultant had approached a colleague with an interest in paediatric oncology and haematology for advice on the management of neutropenic cases. The Consultant gave evidence to the Panel that he had since reflected on the case, and that his practice in communicating with members of his team had improved. The Consultant had also used his spare time to observe practices on a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit. He told the Panel he intended to enrol on an APLS programme and a communication course.

The Panel concluded that he had taken substantial steps to remedy most of the deficiencies in his practice identified by the case. Testimonial evidence indicated he was a safe and competent practitioner. It concluded that his Fitness to Practise was not impaired.

The Panel then went on to consider whether to place a warning on the Consultant’s registration. It decided not to do so, saying:

‘The Panel has noted the circumscribed and case specific character of your misconduct. It has had regard to your creditable professional history. It has acknowledged that what happened in 2007 related to a highly unusual and specific case. It has accepted that there has been no repetition of short comings of any kind. It has taken account of the steps you have taken over remediation, and which are ongoing. It has weighed all the testimonial evidence presented on your behalf.’

The Panel said it found the Consultant to be a safe, competent and valuable practitioner of integrity, and concluded that no useful regulatory purpose would be served by imposing a warning on the doctor’s registration.

The GMC in future

Two significant developments to GMC regulation are in the pipeline.

(a) Revalidation

This concept has been much discussed since the Shipman Inquiry highlighted what has been termed ‘a regulatory gap’ between a doctor’s employer and the GMC.

‘Some doctors [are] judged as “not bad enough” for action by the Regulator, yet not “good enough” for patients and professional colleagues in a local service to have confidence in them. There is thus a significant “regulatory gap” and it is this gap that endangers patient safety.’6

There were a number of public consultations on the concept of ‘revalidation’ as a means of closing this ‘regulatory gap’. The first step towards this process was the requirement since November 2009 that to practise, a doctor must not only be registered, but must also have a licence to practise. Without that licence, it is a criminal offence to practise medicine, write prescriptions, sign death certificates or undertake any other activities which are restricted to doctors holding a licence.

In late 2012, the GMC opens the process of ‘revalidation’ whereby every five years a doctor’s licence to practise must be renewed. To do that, the doctor must be able to demonstrate to his ‘Responsible Officer’ that he is up to date and remains fit to practise.

It is envisaged that every organization providing healthcare will nominate a senior practising doctor to be the GMC’s Responsible Officer. He is likely to be the organization’s Medical Director. He has statutory duties to the GMC and so will be the bridge crossing the gap between local clinical governance and the GMC. His duties will be to ensure that there are adequate local systems for responding to concerns about a doctor, to oversee annual appraisals for all medical staff and to make recommendations for revalidation. He will write a report on the suitability of doctors in his organization for revalidation, based on their annual appraisals over the previous five years, and on any other information drawn from clinical governance systems. Where, as a result of his submissions, the GMC’s Registrar considers withdrawing a doctor’s licence, the doctor will be informed and given 28 days to make representations about it. The Registrar must take those representations into account before making a decision. If he does then decide to withdraw the licence, the doctor will have the right to appeal to a Registration Appeals Panel. Equally, the GMC may well decide to put the matter through its Fitness to Practise Procedures.

What does this mean in practice for the individual doctor? He must keep a portfolio of supporting information for his annual appraisal, showing how he is keeping up to date, evaluating the quality of his work and recording feedback from colleagues and patients. The Royal Colleges for the different medical specialities will advise on the kind of material to be compiled.

The GMC has warned practitioners that appraisal discussions will be more than a mere question of collating material. ‘Your appraiser will want to know what you did with the supporting information, not just that you collected it.’ The doctor will be expected to reflect on how he intends to develop and modify his practice.

Discussions at appraisals may be guided by the principles of the GMC’s Good Medical Practice, which have been helpfully reduced into what are called the ‘Four Domains’, each domain having three ‘Attributes’.

The theory is that a doctor who falls short of any of the required Twelve Attributes should be picked up by the clinical governance system during the 5-year licence cycle, and given the appropriate support, so that his licence will be renewed at the end of the cycle.

The GMC says this about the closure of the ‘regulatory gap’:

‘For the first time, employers, through Responsible Officers, will be required to make a positive statement about the Fitness to Practise of the doctors they employ. With their new responsibilities for overseeing revalidation, employers are more important than ever in promoting high standards of medical practice.’

Critics of the scheme say that a revalidation scheme based on the collection of papers and an annual appraisal will not effectively detect rogue doctors. They say that Shipman would have had his licence renewed. Critics also say that the scheme places too much power and influence in the hands of one person, the Medical Director/Responsible Officer, a feature which, they say, will draw the GMC into the politics of the workplace.

(b) Consensual disposal

Ever since the procedural reforms of 2004, the GMC, sensitive to the criticism that doctors only ever look after their own, has placed a lot of emphasis on the transparency of its procedures. Decisions about impairment and about sanction are made in public at the conclusion of a public hearing (unless the issues under consideration concern a doctor’s health in which case the hearing is in private). This is intended to maintain public confidence in the profession.

However, what has tended to happen is that after several days of exhausting and stressful evidence, although facts may have been proven against the doctor, it turns out that he can show insight and remediation. His Fitness to Practise may have been impaired at the time, but it is now no longer impaired. In that case, there is no finding of impairment and the worst that can happen is a warning. The paediatric example given above is a case in question. Was the hearing worth it?

Add to that the rising number of complaints, the rising number of hearings every year and the rising cost, and we find that the GMC is now thinking about dealing with at least some of its cases in a different way. The phrase ‘consensual disposal’ has been coined for the suggestion that the GMC and the doctor engage in some discussion about agreeing a sanction without the need for a hearing or witnesses. But would this kind of process undermine public confidence and create a perception of deals done ‘behind closed doors’?

A recent consultation showed a large measure of support for the idea in principle. It was thought it might be most suitable for cases where there were no significant disputes about the facts. But it was also considered that there would be some cases in which such a process would be inappropriate, although it was difficult to establish what kind of cases these might be. More detailed proposals on the idea are now being developed by the GMC.

8 The role of the doctor

It is a term of all NHS employment contracts that staff must assist with investigations. Likewise, it is a professional requirement of the GMC’s Good Medical Practice. A doctor who is asked to provide a written statement of events as part of any investigation– whether an internal hospital inquiry or a Coroner’s inquiry must cooperate. Equally, he must be very conscious that what he writes now may be referred to in later proceedings. He therefore needs to be accurate. If there is any risk of trouble in the future, a doctor would be well advised to contact his MDO and ask for his proposed statement to be looked over by a medico-legal adviser.

Witness statements

A doctor who is asked to prepare a witness statement concerning the care of a patient should always be provided with a copy of the relevant set of patient records to assist him.

Although a witness statement should be prepared as soon as possible after the event, so that the details are fresh in the mind, the doctor should not allow himself to be rushed. Accuracy is more important.

Here are some tips on writing a well laid out and clear witness statement:

Formal requirements

- Write on one side of the paper only.

- Type the statement and bind it using one staple in the top left-hand coroner. Have a decent left and right margin and double space the document.

- Use a heading to orientate the reader for example ‘Statement of Bob Smith following the death of Augustus Clark on E Ward at Pilkington Hospital on 22 November 2006’.

- Number the pages and identify the statement in the top right-hand corner of each page for example ‘Page 2 Witness Statement of Bob SMITH’.

- Number paragraphs and appendices.

- Refer to documents and names in capitals and express numbers as figures.

- Attach copies of protocols or other documents referred to for example staff rota or clinical observations chart.

- Sign and date it.

- End with a statement of truth: ‘I believe that the contents of this statement are true.’

- Spellcheck the statement.

Content

- Before starting, decide ‘What are the issues?’

- Write a chronology. This will provide the structure.

- In the first paragraph, witnesses should set out who they are, their occupation and where they work (currently and at the time of the incident). It is important to orientate the reader, so a short CV is helpful. In more complex cases a fuller CV can be appended

- There should be a main heading and subheadings.

- Use short sentences (a sentence that goes on for more than 2 lines may be too long) and paragraphs (aim for about 3 sentences per paragraph).

- Do not stray into another witness’s evidence.

- Statements should contain no retrospective opinions, only contemporaneous opinions. Avoid statements like, ‘I thought for years this was going to happen.’ Contemporaneous opinions should be backed up by facts. So, when stating a professional opinion, for example a diagnosis, explain the thinking behind the opinion

- Do not use jargon. If technical terms have to be used, consider the use of a glossary and/or diagrams. Try to make the statement accessible to a nonclinician.

- Avoid pseudo-legal language such as ‘I was proceeding in a northerly direction …’

- Identify individuals as they are introduced to the narrative.

- Ambiguous expressions such as ‘I would have done such and such’ should be avoided. If the doctor does not recall what he did, he should say so clearly. If, based on his normal practice, he believes he did such and such, then this should be made clear too.

Presenting oral evidence

Having looked at negligence claims, disciplinary hearings, Coroner’s hearings and GMC hearings, it is appropriate to say a few words about how to give evidence. For the way a witness presents his evidence affects the weight given to it by the Court/Inquiry/Tribunal.

Remember that a witness’s role is to assist the Tribunal. He is not there to argue with the barrister.

The barristers may try to draw witnesses into an argument. They may also use other techniques to disconcert them, such as moving between multiple documents. Once the witness recognizes that they are just techniques, they can watch out for them and so remain in control.

The lawyer is only doing his job. Witnesses have to separate themselves from the evidence and not get angry.

Before giving evidence, witnesses should:

- reread and think about all the evidence including the records, protocols, national guidelines and professional standards;

- reread witness statements and Court/Inquiry documents (if appropriate) and ask their lawyer to explain anything they do not understand;

- check with the lawyers whether there are any other documents they would like the witness to read, such as clinical studies;

- tell the lawyers about any mistakes or omissions in the witness statement;

- visit the courtroom beforehand; ask the Court for a tour;

- if possible see the Court/Inquiry ‘in action’ beforehand;

- plan the route to the hearing, arrange where to meet everyone and work out what to wear;

- exchange telephone numbers with the legal team;

- put the Court telephone number into their mobile phone;

- practise taking the oath and giving their credentials.

At the hearing

- report to the reception desk where you will need to register;

- be prepared to come into contact with family members and media representatives;

- keep conversations to a minimum and nonverbal communications appropriate;

- on entering the courtroom sit down and do not talk;

- stand up when the Judge/Panel arrives and then be seated;

- the proceedings will be recorded; be prepared to speak clearly and slowly;

- pause before answering any questions;

- listen carefully to the question;

- deliver your answers to the Judge/Panel; the best way to ensure this is to stand with your feet facing the Judge/Panel and turn from the hips to take questions from the lawyers;

- try to keep answers to questions brief and to the point;

- try to eliminate passion from your answers.

No-one, not even a seasoned expert witness enjoys the stress of giving evidence. But to do so is part of a doctor’s professional duty.

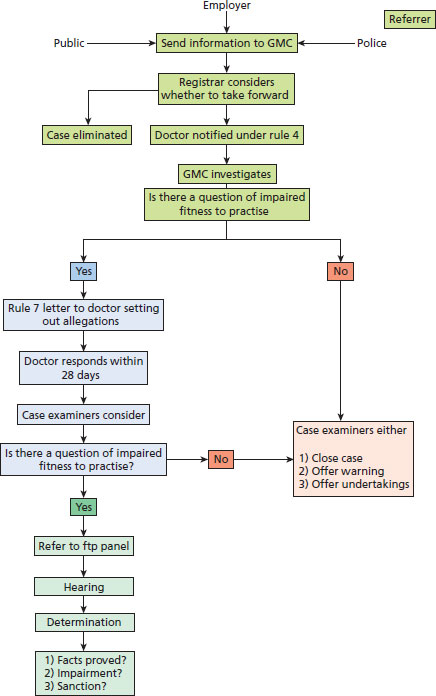

Figure 3.1 Fitness to practice procedure: a summary.