Prepubescent problems

Vaginal discharge

Most newborn girls have some mucoid white vaginal discharge. This is normal and disappears by about 3 months of age.

Vulvovaginitis

This is the most common gynaecologic problem in childhood, usually occurring in girls aged between 2 years and the start of puberty. The vaginal skin in childhood is thin and atrophic. Overgrowth of mixed bowel flora occurs in this environment and the resultant discharge can be an irritant to the vulval area, which is also atrophic. The moist environment between the opposed skin surfaces may also be exacerbated by urine dribbling, particularly in an obese young girl.

Presentation

- Erythema/irritation of the labia and perineal skin.

- Itch and dysuria may also be present.

- ± offensive vaginal discharge.

Management

Investigations are usually not required. If urinary symptoms are present, check the urine to exclude urinary tract infection (UTI).

- Explanation and reassurance.

- Vinegar (1 cup white vinegar in a shallow bath).

- Simple soothing, barrier cream to the labial area (e.g. zinc–castor oil or nappy rash cream).

- Toileting/hygiene advice: avoid potential irritants such as soaps and bubble bath.

Rarely, if the problem persists, further action may be required. The natural history is for recurrences to occur up until the age when oestrogenisation begins.

- If a heavy discharge persists or marked skin inflammation beyond labial contact surfaces is present, take swabs from the perineum in case of an overgrowth of one organism (e.g. group A Streptococcus) and treat it with the appropriate antibiotics (usual culture findings are mixed coliforms).

- Do not take vaginal swabs, as it is painful and distressing. If swabs for culture are required, introital area swabs are adequate.

- If itch/irritation is the main complaint, consider pinworms.

- If eczema occurs elsewhere on the body, this can be superimposed on the irritated skin. Combined treatment of the vulvovaginitis (as above) and hydrocortisone may be indicated.

- Foreign bodies are a potential cause for a persistent, unresolving, often blood-stained discharge. An examination under anaesthesia with vaginoscopy is required to exclude this.

- Although it is rare, consider sexual abuse if other indicators are present.

Thrush is rare in prepubertal girls unless there has been significant antibiotic use. Thrush thrives in an oestrogenised environment, not in the atrophic setting.

Note: Vaginal pessaries should never be prescribed to prepubertal girls.

Vaginal bleeding

Many girls will have some vaginal bleeding in the first week of life, caused by the withdrawal of maternal oestrogens. This is normal. In older girls bloodstained discharge may indicate:

- Vulvovaginitis: associated with atrophic changes (see vulvovaginitis).

- A foreign body: particularly if it is persistent despite management of vulvovaginitis.

- Trauma (including straddle injuries and sexual abuse).

- Excoriation secondary to threadworms or eczema.

- Haematuria.

- Urethral prolapse.

Urogenital tract tumors are rare, and usually a mass is also present at time of presentation.

Labial adhesions

- Labial adhesions are seen in infancy and usually resolve by about 8 years. They may occasionally persist through to puberty but will resolve around the time of menarche.

- The adhesion is not congenital, but acquired from a secondary adherence of the atrophic surfaces of the labia minora, presumably as a result of irritation.

- Uncomplicated labial adhesions in girls do not need division. Refer to a specialist if the child has difficulty voiding or recurrent UTIs. Treat vulvovaginitis or nappy rash if present. Parents should be reassured that the labia will separate when oestrogenisation occurs as the child grows. Although it is possible to divide the adhesions with lateral traction this is frequently distressing for the child and the parents and recurrence is common.

- The use of topical oestrogen cream is unnecessary and is associated with significant rates of failure and recurrence.

Dysmenorrhoea

Clinical features

- Cramping lower abdominal pain, lower back pain and pain radiating to the anterior aspects of the thighs with menses (symptoms may begin a few days before menstruation).

- Associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, change in bowel actions (usually softer bowel actions or diarrhoea, but occasionally constipation), headaches and general lethargy may occur. These symptoms should be looked for as they support the diagnosis of a prostaglandin-induced dysmenorrhoea. Occasionally these symptoms may begin intermittently a few months before menarche.

- Stress will often precipitate more severe episodes of dysmenorrhoea.

- Vaginal examination is not done if the young woman is not sexually active, and even then only with careful consent. Occasionally, vaginal examination in young women who are using tampons may be possible, but alternatives such as a transabdominal pelvic ultrasound examination will usually provide all the required information (e.g. obstructive congenital anomalies and ovarian cysts).

Management

- General measures: assess and manage other adolescent issues (see chapter 15, Adolescent health) and encourage exercise.

- Antiprostaglandins (e.g. mefenamic acid, naproxen, ibuprofen; see Pharmacopoeia) should ideally be commenced before the onset of symptoms. Failure to respond to one type of antiprostaglandin warrants the trial of an alternative type.

- Hormonal treatment can be used to regulate the menstrual cycle if it is too irregular for prophylactic antiprostaglandins. The oral contraceptive pill (OCP) can also be used for dysmenorrhoea. This may be the first line treatment, particularly in a sexually active teenager.

- Non-responsive or worsening dysmenorrhoea will require investigation. Pelvic ultrasound can usually identify an obstructive congenital anomaly and detect significant endometriosis (e.g. an endometrioma).

- Diagnostic laparoscopy may identify mild endometriosis. However, the value of treating this with specific hormonal therapy or operative laser diathermy is unclear from both the short-term and long-term perspective. Therefore, this invasive investigation should be withheld until optimal management with antiprostaglandin therapy or OCP, or both, has been tried, and other adolescent issues explored.

Amenorrhoea

Primary

See chapter 25, Endocrine conditions, Delayed puberty, p. 316.

Secondary

Consider the following diagnoses:

- Pregnancy.

- Weight loss/anorexia nervosa.

- Strenuous exercise.

- Stress (e.g. exams, social/family or travel).

- Polycystic ovaries.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Irregular menses with multiple follicles found on pelvic ultrasound and

- Signs of excess androgen (severe acne and/or hirsutism).

- Obesity is a common association.

Care needs to be taken, as many teenagers who have multiple follicles found on pelvic ultrasound are inappropriately told they have PCOS. Without the associated features, multiple follicles (10–20) are completely normal. These patients often have irregular, infrequent periods rather than amenorrhoea.

Investigations can help confirm the diagnosis (e.g. follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinising hormone and pelvic ultrasound).

Management

- Addressing obesity (see chapter 8, Obesity) can significantly improve the other features of PCOS.

- Amenorrhoea itself does not need treatment, but associated problems may require intervention.

- Hirsutism responds to OCP containing cyproterone acetate (an antiandrogen). This initiates withdrawal bleeds, which are lighter and more regular.

- Infertility: irregular ovulation may impede fertility. Specialist advice is recommended when planning conception.

- Osteopenia: prolonged amenorrhoea associated with low oestrogen levels potentially leads to a negative effect on bone mineral density. The addition of hormonal treatment may then be indicated.

Metrostaxis (severe heavy loss)

See also chapter 29, Haematologic conditions and oncology.

Investigations

- Check haemoglobin (Hb).

- Check clotting profiles: APPT, INR, vWF, collagen-binding assay (CBA), platelet function (platelet function assay, PFA-100) or platelet aggregometry.

- Exclude pregnancy.

Management

- Tranexamic acid (TEA): antifibrinolytics work via non-hormonal pathways to reduce the degree of blood loss. It can be used in combination with hormonal treatment.

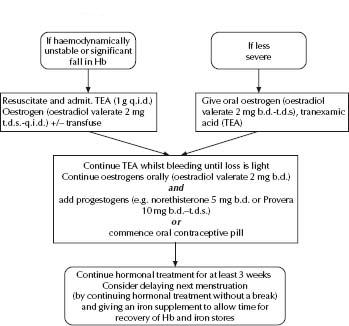

- Oestrogen therapy is usually required for a young woman having her first or second period (Fig. 28.1).

- Progestogen therapy is more appropriate for a young woman who has been menstruating for some time (Fig. 28.2)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree