Acute infectious gastroenteritis

The most common cause is rotavirus infection, with the seasonal peak period during autumn and winter in Australia. It is responsible for 40–50% of cases requiring hospital admission, while adenovirus infection causes between 7–17% of cases. Bacterial gastroenteritis is less common, causing 5–10% of all cases; causes include Salmonella spp., Campylobacter jejuni, Yersinia enterocolitica and Escherichia coli. Parasites, such as Cryptosporidium, are also a known cause of acute gastroenteritis.

The two most important issues in the management of acute infectious diarrhoea are:

- Exclusion of other important causes of vomiting and diarrhoea.

- Adequate assessment and treatment of dehydration.

Differential diagnoses of vomiting and diarrhoea

- Appendicitis.

- Urinary tract infection.

- Other sepsis (including meningitis).

- Other surgical conditions including intussusception, enterocolitis associated with Hirschsprung disease and malrotation of the bowel.

- Haemolytic uraemic syndrome.

Clinical features

Presenting symptoms include poor feeding, vomiting and fever, followed by diarrhoea. Stools are frequent and watery in consistency. Bacterial gastroenteritis is suggested by a history of frequent small-volume stools with passage of blood and mucus, and abdominal pain. Be wary of diagnosing gastroenteritis in the child with vomiting alone who is dehydrated or unwell.

It is essential that all children with acute onset of vomiting, diarrhoea and fever are reevaluated regularly so as to confirm the diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis and adequacy of rehydration therapy.

Assessment of dehydration (see Table 27.1)

- Risk of dehydration is increased with younger age, as infants (<6 months) have an

- increased surface area : body volume ratio resulting in increased insensible fluid losses.

- Recent change in body weight provides the most accurate indication of fluid depletion. Starvation produces no more than 1% body weight loss per day.

- Decreased skin turgor and peripheral perfusion accompanied by deep (acidotic) breathing are the only signs proven to discriminate between dehydration and hydration.

- Actual degree of dehydration may be underestimated with obesity and overestimated with wasting or sepsis.

<5% body weight loss represents no or mild dehydration

5–9% body weight loss represents moderate dehydration

>9% body weight loss represents severe dehydration.

Note: These percentages are approximate and given only as a guide.

Table 27.1 Guidelines to assessment and management of dehydration

| Assessment of dehydration | Management |

| Mild: ≤5% body weight loss | Rehydrate over 6 h with ORS/water |

| dry mucous membrane* | ORS only is preferred in high-risk patients (infants <6 months) |

| thirsty, alert and restless | |

| Moderate: 5–9% body weight loss | May require rehydration via the nasogastric route |

| all of the above signs (mild group) | Re-assessment (including body weight and clinical examination) is required at 6 h |

| PLUS | |

| rapid pulse | If fluid replete, maintenance age-appropriate fluids can then be used |

| decreased peripheral perfusion* | |

| sunken eyes and fontanelle | Weigh inpatients every 6 h during the first 24 h of admission |

| deep acidotic breathing* | |

| pinched skin retracts slowly (1–2 s)* | Introduce food intake after rehydration, if dehydration has been corrected |

| Severe: >9% body weight loss | If shock is present, give normal saline 20 mL/kg i.v. (repeated fl uid boluses may be required until organ perfusion is restored) |

| PLUS | |

| in infants – drowsy, limp, cold, sweaty, cyanotic limbs and altered conscious level | Can start ORS once initial resuscitation is completed – give over 6 h |

| Following rehydration, the same general principles as those for mild–moderate group apply | |

| in children – apprehension, cold, sweaty, cyanotic limbs, rapid feeble pulse and low blood pressure |

* These are the only signs proven to discriminate between hydration and dehydration (4% or greater).

Guidelines to management of acute gastroenteritis

Hydration

- For children/infants with dehydration, rapid enteral rehydration over 4–6 h is now suggested (see Table 27.1). Past regimens aimed at gradual rehydration over 24 h were not evidence based. The exceptions are children with significant neurological or biochemical disturbance (see sections on hyper- and hyponatraemic dehydration below).

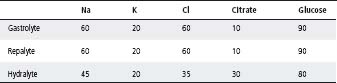

- Most children/infants with dehydration can be safely and adequately rehydrated using oral rehydration solutions (ORS) (Table 27.2). If these are not tolerated by the oral route, nasogastric administration is an alternative. Vomiting is not a contraindication to a nasogastric tube.

- Oral rehydration solutions use the principle of glucose-facilitated sodium transport in the

- small intestine. The solutions currently used in Australia are outlined in Table 27.3.

- Parent education is vital, especially in the outpatient management of children. The important message is the need to drink more fluid more often, which is best given in small volumes and frequently (see Table 27.4). It should be emphasised that home-made solutions and ORS should be carefully prepared according to instructions provided, as they can be potentially dangerous if made up incorrectly.

Nutritional management

Early re-feeding (after rehydration) has been shown to enhance mucosal recovery in children/ infants with acute gastroenteritis and reduces the duration of diarrhoea.

- Breast-feeding should continue through rehydration and maintenance phases of treatment.

- Formula-fed infants and children should re-start oral age appropriate formula or food intake after completion of rehydration.

- Children can have complex carbohydrates (e.g. rice, wheat, bread and cereals), yoghurt, fruit and vegetables once rehydration is complete.

Transient lactase deficiency with acute gastroenteritis may occur but is not common in infants <6 months. Lactose-free diets are infrequently required after acute gastroenteritis. If there is persistent diarrhoea after re-introduction of feeds, evidence for lactose intolerance should be sought (stool pH <5 and ≥0.75% reducing substances). A lactose-free formula can be used if the patient is lactose intolerant.

Admission to hospital

- Infants/children who have moderate or severe dehydration.

- Patients at high risk of dehydration on the basis of young age (<6 months) with a high frequency of diarrhoea (8 per 24 h) and vomiting (>4 per 24 h) should be observed for 4–6 h to ensure adequate maintenance of hydration.

- High-risk infants/children (e.g. ileostomy, short gut, cyanotic heart disease, chronic renal disease, metabolic disorders and malnutrition).

- Infants/children whose parents and carers are thought to be unable to manage the child’s condition at home.

- If the diagnosis is in doubt.

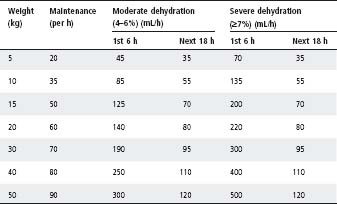

Table 27.2 Recommended hourly oral or nasogastric rehydration rate for children

The daily fluid requirement is relatively high in neonates (150 mL/kg per day), reducing to 100 mL/kg per day in older infants and 80 mL/kg per day between 1 and 5 years.

Table 27.3 Oral rehydration preparations available for use in Australia (concentrations are expressed as mmol/L of made-up solution)

Table 27.4 Suitable fluids for non-dehydrated children

| Solution | Dilution |

| Sucrose (table sugar) | 1 teaspoon in 200 mL boiled water |

| Fruit juice | 1 in 6 with tap water |

| Cordials | 1 part in 16 parts water |

| Lemonade | 1 part in 6 parts water |

Do not use undiluted or low-calorie lemonade or fruit juice.

Biochemical investigations

Glucose, electrolyte and acid–base studies are required in children with:

- A history of prolonged diarrhoea with severe dehydration.

- Altered conscious state.

- Convulsions.

- Short-bowel syndrome, ileostomy, chronic cardiac, renal and metabolic disorders.

- Infants <6 months of age who are judged as being dehydrated.

Pharmacotherapy

- Infants and children should not be treated with antidiarrhoeal agents, as there is no substantial clinical evidence to suggest that this treatment alters symptoms.

- Most bacterial infections do not require antibiotics.

- Salmonella or Campylobacter gastroenteritis may require antibiotic treatment (see chapter 30, Infectious diseases).

- Shigella dysentery requires antibiotic treatment.

Complications

Hypernatraemic dehydration (sodium >150 mmol/L)

- Results from severe water and sodium depletion with greater loss of water. This can lead to severe neurological sequelae if rehydration is not carried out appropriately.

- Oral rehydration therapy is preferred to i.v. rehydration. If the patient is in shock, give a bolus of normal saline 20 mL/kg i.v., repeat until organ perfusion is restored.

- Following this, ‘slow ORT’ aiming to complete rehydration over 12 h is required, followed by maintenance fluids.

- Serum electrolytes should be monitored on a 4 hourly basis. As a guideline, serum sodium should not fall by >0.5 mmol/L per hour.

- Consultation with an intensive care unit is recommended for these patients.

Hyponatraemic dehydration (serum sodium <130 mmol/L)

- Can cause seizures and coma, and requires consultation with an intensive care unit.

- Be aware of iatrogenic hyponatraemia due to fluid (hypotonic) overload.

Lactose intolerance

Following infectious diarrhoea, infants may have temporary lactose intolerance. This sequela of acute gastroenteritis used to be prominent in infants <6 months of age, but it is now uncommon. This may be due in part to early oral feeding which aids mucosal recovery. Clinical features of sugar intolerance include:

- Persistently fluid stool.

- Excessive flatus.

- Excoriation of the buttocks.

- Typically, these infants appear well.

Diagnosis

Collect the fluid stool in napkins lined with plastic. Dilute 5 drops of stool with 10 drops of water. Add a Clinitest tablet. A colour reaction corresponding to ≥0.75% or more reducing substance indicates that sugar intolerance is present.

Management

- Breast-feeding should continue unless there are persistent symptoms with buttock excoriation and failure to gain adequate weight.

- Formula-fed infants should be placed on a lactose-free formula for 3–4 weeks.

Note: A clinical response after change to soy formula may indicate either post-infectious lactose intolerance or allergy to cow’s milk protein, as soy formulae available in Australia are lactose-free.

Monosaccharide intolerance

Infrequently, infants with severe bowel damage secondary to gastroenteritis may be unable to absorb normal amounts of monosaccharide such as glucose or fructose. Diarrhoea will continue even with a lactose-free formula. Monosaccharide intolerance requires specialist consultation.

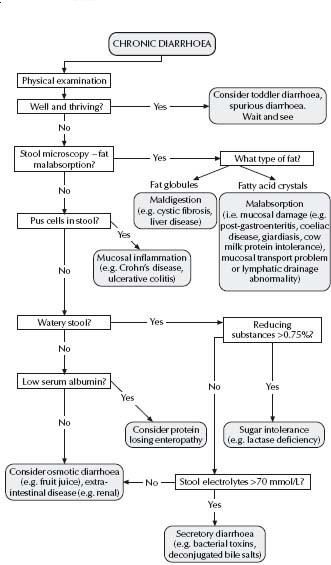

An increase in stool frequency or fluid content is often of concern to parents, but does not necessarily imply significant organic disease, although this needs to be excluded. In every child who presents with chronic diarrhoea, the decision must be made as to whether further investigation is required. The algorithm in Fig. 27.1 outlines an approach to the child with chronic diarrhoea.

Toddler diarrhoea

This is a clinical syndrome characterised by chronic diarrhoea often with undigested food in the stools of a child who is otherwise well, gaining weight and growing satisfactorily. Stools may contain mucus and are passed 3–6 times a day; they are often looser towards the end of the day.

- Onset is usually between 8 and 20 months of age.

- Often there is a family history of functional bowel disease, such as irritable bowel syndrome.

- The treatment consists of reassurance and explanation. No specific drug or dietary therapy has been shown to be of value in toddler diarrhoea. Some toddlers on a high-fructose intake may have (‘apple-juice’) diarrhoea that responds to dietary change.

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune enteropathy triggered by the ingestion of gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. The prevalence of this disorder amongst flrst-degree relatives is approximately 10%. The clinical expression of this disorder is more heterogeneous than previously thought (Table 27.5) and onset may be at any time, after years without symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree