Important principles

- Eye examination:

– Always test and record vision as the first part of any eye examination.

– In infants, observe following and other visual behaviour and listen to the parents’ impressions of their child’s vision.

- Instilling eye drops:

– Do not use local steroid drops unless corneal ulceration has been excluded by fluorescein staining. Only use steroids for short periods (2 days or less), unless an ophthalmologist directs otherwise.

– Instilling eye drops/ointment in a young child: carer sits on the floor with legs extended; lay child between carer’s legs with child’s arms under the carer’s thighs and the child’s feet near the carer’s feet. This leaves the child’s head secured and the carer with both hands free to hold open the child’s eyelids and instil eye medication.

- Padding eyes:

– Never pad a discharging eye.

– Pad an eye or keep the child indoors if local anaesthetic has been instilled, until the effect of the local anaesthetic has worn off (10–20 min).

- Referral to an ophthalmologist:

– Transient malalignment of the eyes is common up to 6 months of age. However, a child with a transient squint after 6 months or a constant squint at any age should be referred promptly to an ophthalmologist. True squints rarely improve spontaneously.

– All children with a white red-reflex or white masses in the retina must be referred immediately to an ophthalmologist to exclude retinoblastoma.

– In cases of photophobia or watery eyes with no significant discharge in the first year of life, consider congenital glaucoma.

Trauma to the eye can take many forms. Physical trauma to the eye and surrounding structures may be blunt or sharp. Trauma can also result from radiation (thermal and electromagnetic) and chemical agents.

Foreign bodies

Foreign bodies on the surface present with a painful, watery eye. If a foreign body or corneal ulcer is suspected, instil 1 drop of local anaesthetic to ease the pain and facilitate examination. Suitable local anaesthetics are proxymetacaine 0.5%, amethocaine 0.5 or 1%, or benoxinate 0.4%. Do not use local anaesthetics for the continuing treatment of ocular pain under any circumstance.

Conjunctival foreign bodies are common and often found on the posterior surface of the upper lid. Therefore, eversion of the lid is essential. Most foreign bodies are easily removed with a moist cotton wool swab. If they are embedded and/or difficult to remove, refer the child to an ophthalmologist. Beware of an iris naevus (small pigmented lesion on the iris that can be mistaken for a corneal foreign body) or iris prolapse through a perforating injury of the cornea mimicking a corneal foreign body.

Intraocular foreign bodies are generally the result of high-velocity fragments. Suspect them if the history involves an explosion, metal(s) striking on metal, or any other situation that involves high-speed objects (e.g. power tools or a lawn mower). If the history is at all suggestive, even in the absence of local signs, radiography of the orbit (AP and lateral) is necessary. If an intraocular foreign body is demonstrated or suspected, immediate referral to an ophthalmologist is mandatory.

Eyelid injuries

All eyelid lacerations except the most minor should be repaired under general anaesthesia. Refer to an ophthalmologist if lacerations involve the lid margin or the medial aspect of the eyelids (canalicular injury is likely).

Hyphaema (blood in the anterior chamber)

This is the result of blunt trauma to the eye and all cases require referral to an ophthalmologist. The potential complications include other eye injuries, secondary haemorrhage and vision loss. Minor hyphaemas can be managed as an outpatient. More significant hyphaemas require admission and bed rest.

Fracture of the orbital bones

A blowout fracture through the wall of the orbit is suspected if ≥1 of the following three cardinal signs are present:

- Restricted movement of the eye, particularly in a vertical plane, with double vision.

- Infra-orbital nerve anaesthesia.

- Enophthalmos – this may be difficult to assess initially because of eyelid haematoma.

Diagnosis is usually clinical. Refer to an ophthalmologist before organising a CT scan. A CT scan is used to demonstrate the fracture of the orbital wall and entrapped orbital tissue (the classic sign is a tear-drop ‘polyp’ hanging from the roof of the maxillary antrum).

Penetrating injury (including intraocular foreign body)

This should always be considered in patients with lacerations involving the eyelids, particularly after motor vehicle accidents. Clinical clues include distortion of the pupil, prolapse of the iris through the cornea, or presence of pigmented tissue over the sclera. If suspected, protect the eye with a cone or shield that does not place pressure on the eyelids or eye and admit. Prevent vomiting with an antiemetic, as this may cause extrusion of eye contents. Refer to an ophthalmologist immediately.

Chemical burns

Irrigate the eye with saline or water copiously for 15 min using an i.v. giving set under local anaesthesia. Continue this until the fluid is neutral on pH testing. Refer all chemical burns to an ophthalmologist.

Thermal burns

The ocular surface is rarely involved. Check for ulceration with fluorescein staining. Butesin picrate ointment is suitable for use on lid burns. Secondary lid swelling may result in corneal exposure and should be treated with ocular lubricants.

Non-accidental injury

The presence of retinal haemorrhages in cases of unexplained head injury raises the possibility of non-accidental injury. Appropriate investigation of the circumstances of the injury should be initiated. The retinal haemorrhages must be assessed by an ophthalmologist (refer to chapter 17, Child abuse)

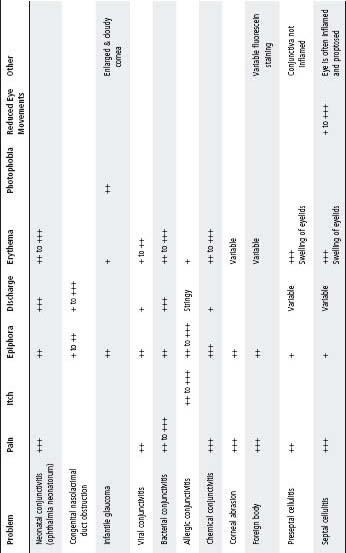

Common causes of the acute red eye are conjunctivitis, corneal ulceration, corneal or conjunctival foreign bodies (see above). Less common causes are preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Table 26.1 gives a brief outline of the presenting features of red, sticky and watery eyes, which have a large number of causes and whose clinical presentations may overlap.

Conjunctivitis

Aetiology

- Bacterial: generally pus is present.

- Viral: generally there is watery discharge.

- Allergic: history of atopy and ‘itchy eyes’.

Neonatal conjunctivitis (ophthalmia neonatorum)

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Clinical. Presents within a few days of birth with acute, severe, purulent discharge associated with marked conjunctival and lid oedema (‘pus under pressure’).

- Diagnosis. Urgent Gram stain for Gram-negative intracellular diplococci and direct culture to appropriate culture media.

- Treatment. This is an ocular emergency because of the risk of corneal perforation. Admit and give i.v. cefotaxime 50 mg/kg 8 hourly for 7 days (dose may need adjustment according to age and birthweight). Penicillin (same duration) is an alternative if the organism is known to be susceptible. In all cases local measures such as ocular lavage and topical antibiotics (chloramphenicol) may be helpful.

- Investigate and treat the mother and partner.

Table 26.1 The causes of red, watery and sticky eyes

Chlamydia

- Usually occurs at 10–14 days of age. Fails to respond to routine topical antibiotics. If left untreated, there is a risk of pneumonitis.

- Diagnosis. Giemsa stain of conjunctival scraping for intranuclear inclusions. Also antibodies in tears and immunofluorescent stains of conjunctival scrapes. Use a Chlamydia kit, ensuring conjunctival cells are collected.

- Treatment. Erythromycin 10 mg/kg oral 8 hourly for 21 days and eye toilet.

- Investigate and treat the mother and partner.

Other bacteria

- Other causes of conjunctivitis are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus or diphtheroids. Culture and treat with chloramphenicol eye drops/ointment. A rapid clinical response is anticipated.

- Occasionally Neisseria meningitidis can cause conjunctivitis and should be treated as for invasive infection (see chapter 30, Infectious diseases).

Blocked nasolacrimal duct

Presents with mucopurulent discharge with a watery eye. On waking the discharge is worse and conjunctiva is not inflamed (see Watering eyes, p. 332).

Conjunctivitis in older children

Bacterial

- Severe: Chloramphenicol eye drops: 2 hourly by day and ointment at night.

- Less severe: Chloramphenicol eye drops or ointment three times a day.

Viral

- This condition usually clears spontaneously.

- If it is unclear whether the infection is viral or bacterial, chloramphenicol eye drops may be given.

Herpes simplex conjunctivitis

- Suspect if the child has eyelid vesicles.

- Check for corneal ulceration and treat with 4 hourly aciclovir ointment if ulceration is present.

- Refer to an ophthalmologist.

Allergic

- In mild cases use an astringent (phenylephrine 0.12% or naphazoline 0.1%).

- In moderate cases use a topical antihistamine (antazoline 0.5%).

- In severe cases refer to an ophthalmologist. Topical steroid or sodium cromoglicate should only be given under the supervision of an ophthalmologist.

Corneal ulceration

Ulceration causes pain, photophobia, lacrimation and blepharospasm. It is diagnosed by eye examination – fluorescein stain after the instillation of a local anaesthetic.

For causes and management, see Table 26.2.

Periorbital and orbital cellulitis

Both periorbital and orbital cellulitis present with erythematous, swollen lids in a febrile child. Orbital cellulitis is differentiated by the presence of proptosis and ophthalmoplegia. Hence the lids must be separated (a Desmarres lid retractor may be used) to enable a thorough examination.

Periorbital (preseptal) cellulitis

Periorbital (preseptal) cellulitis refers to infection in the soft tissues of the eyelids. This may arise from purulent conjunctivitis, dacryocystitis, or gain entry via local trauma or insect bite.

- Distinguish this from a periorbital allergic reaction. A well child, who has eyelid swelling with minimal or no erythema, fever, tenderness nor local warmth, is quite likely to have an allergic reaction to an allergen that has been blown or rubbed into the eye, or secondary to an insect bite. In this case no specific radiological imaging is required. An oral antihistamine may be used. The child should be reviewed if the swelling does not settle in the next 24 h or if signs of inflammation develop (fever, pain or unwell child).

Recommended antibiotics

In children who are systemically unwell, use both cefotaxime and flucloxacillin initially (Table 26.3). Any child in whom there is a reasonable suspicion of primary skin infection, or who is not improving on flucloxacillin alone should have cefotaxime added. Failure to respond in 24– 48 h may indicate orbital cellulitis or underlying sinus disease – treat as for orbital cellulitis.

Orbital (septal) cellulitis

Orbital (septal) cellulitis occurs when infection is present around and behind the globe of the eye, and is usually due to spread from sinus infection (especially the ethmoid sinuses). It usually occurs in children >2 years. Orbital cellulitis is a medical emergency and should be treated with the same level of urgency as meningitis or a brain abscess. The potential for loss of vision and suppurative intracranial complications is significant.

Table 26.2 Causes and management of corneal ulceration

| Cause | Management |

| Trauma (with or without a foreign body) | Chloramphenicol ointment (1%) and pad if possible |

| Review in 24 h. If not healed in 48 h, refer to an ophthalmologist | |

| When ulcer has healed, continue chloramphenicol ointment twice daily for 1 week | |

| Herpes simplex (dendritic ulcer) | Aciclovir eye ointment (1 cm inside the lower conjunctival sac) 5 times a day for 14 days and refer to an ophthalmologist |

Table 26.3 Recommended antibiotics in periorbital cellulitides

| Mild | Amoxicillin/clavulanate (400/57 mg per 5 mL) 12.5–22.5 mg/kg per dose p.o. 12 hourly |

| Moderate | Flucloxacillin 50 mg/kg (2 g) i.v. 6 hourly |

| Severe OR under 5 years of age and non-Hib immunised (treat as for orbital cellulitis) | Flucloxacillin 50 mg/kg (2 g) i.v. 6 hourly and cefotaxime 50 mg/kg (2 g) i.v. 6 hourly |

Orbital cellulitis is differentiated from periorbital cellulitis by the presence of:

- Chemosis.

- Proptosis.

- Ophthalmoplegia.

- Systemic symptoms.

If the features of orbital cellulitis are present, a CT scan is required to determine if the sinusitis is complicated by abscess formation. This is most commonly a subperiosteal abscess on the medial wall of the orbit adjacent to the ethmoid sinus, which requires surgical drainage (usually by an external ethmoidectomy approach). If no abscess is present, treatment is by i.v. antibiotics alone; however, CT scanning may need to be repeated if there is clinical deterioration, or if there is lack of improvement with medical treatment.

Recommended antibiotics

Flucloxacillin 50 mg/kg (max. 2 g) 4–6 hourly and cefotaxime 50 mg/kg (max. 2 g) 6 hourly. See also Antimicrobial guidelines.

AND Urgent ENT and ophthalmology consultation are required in suspected orbital cellulitis.

Watery eyes are common in children and are the result of either poor tear drainage or overproduction. The latter is usually the result of eye irritation and causes include foreign bodies (see p. 327), corneal ulcer (see p. 331), conjunctivitis (see p. 328) and infantile glaucoma (see p. 334).

Nasolacrimal duct obstruction is the most common cause of watery eyes and discharge that persist after the first 2 weeks of life. The discharge is worse on waking and the conjunctiva is not inflamed. It usually resolves spontaneously, due to an opening of the lower end of the nasolacrimal duct. Local eye cleaning is usually the only treatment indicated. If the eye is red and inflamed, topical framycetin sulfate eye drops may be given (avoid repeated courses of chloramphenicol). If the discharge and watering have not settled by 12 months of age, refer to an ophthalmologist for probing.

Strabismus or squint (turned eye)

Refer all children with squint or suspected squint to an ophthalmologist. This will allow early detection (and possibly prevention) of amblyopia and detection of any underlying pathology such as retinoblastoma or cataract. Examine the red reflex of all children suspected to have a squint; if the reflex is abnormal (very dull or white) urgent referral to an ophthalmologist is required to exclude cataract or retinoblastoma.

A child does not ‘grow out of’ a squint. However, in the first few months of life, babies may have an intermittent squint, especially when feeding. A child of any age with a constant large-angle squint or a child over 6 months with any squint (constant or intermittent) should be referred to an ophthalmologist. All children with a first-degree relative with a squint should be seen by an ophthalmologist at about 3–3.5 years of age, even if there is no squint, as they may have a refractive error alone.

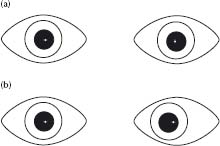

A pseudo-strabismus (pseudo-squint) is due to a broad nasal bridge or epicanthic folds, or both. This results in the appearance of a squint, but corneal light reflexes are central and there is no movement on cover testing (see Figs 26.1 and 26.2). Only make the diagnosis of pseudo-strabismus if absolutely certain. Refer doubtful cases to an ophthalmologist.

- Styes are acute bacterial infections of an eyelash follicle. They occur at the eyelid margin and are red and tender. Removing the lash directly related to the stye will often result in discharge of pus and hasten its resolution. Local antibiotics are sometimes indicated. Systemic antibiotics are rarely needed.

- A chalazion is an obstructed tarsal (or meibomian) gland. These glands are situated within the substance of the eyelid and thus a chalazion will present as a lump within the eyelid. There may be no associated symptoms. Redness associated with a chalazion is usually the result of sterile inflammation due to leakage of the contents, rather than a bacterial infection. Thus local or systemic antibiotics seldom influence the natural history of these lesions. Warm compresses may hasten resolution. If the chalazion is persistent (>6 months), large or causes discomfort, incision and drainage under general anaesthesia may be indicated.

- Ptosis is a droopy or lowered upper eyelid. In children it is usually the result of a minor and isolated anomaly in the development of the levator muscle. It may be unilateral or bilateral, and is sometimes inherited in a dominant manner. If the lowered eyelid obstructs the pupil in a young child, visual loss will occur secondary to amblyopia. Urgent referral to an ophthalmologist is appropriate in such cases. In more minor degrees of ptosis, surgical intervention is for cosmesis and is less urgent.

Fig. 26.1 Corneal light reflex. Shine a light at the child’s eyes and observe the reflection. (a) Eyes are straight and the corneal light reflex is symmetrical. (Note: It is displaced slightly to the nasal side of the centre in each eye.) (b) Left convergent strabismus. The reflection from the deviated eye is displaced laterally

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree