Dental development

Primary dentition

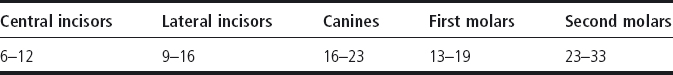

Teeth start to form from the 5th week in utero and may continue until the late teens or early twenties. The first teeth to erupt are usually the lower central primary incisors at around 7 months of age. Table 22.1 summarises the eruption dates for primary teeth.

An infant who shows no sign of any primary teeth by the age of 18 months should be referred to a paediatric dentist.

By the age of 2.5 years most children will have a complete primary dentition consisting of 20 teeth: 8 incisors, 4 canines, 8 molars. In most cases all primary or deciduous teeth are ultimately replaced, but some individuals are missing permanent teeth and primary teeth may be retained into adulthood.

Permanent dentition

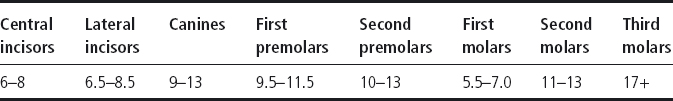

At around the age of 6 years the primary incisors become mobile and fall out. The tooth fairy then comes to visit. The permanent dentition begins to develop, starting with the eruption of the lower first permanent molars (Table 22.2). Permanent teeth are much larger than the primary predecessors and often look more yellow or cream in colour. The period that follows, referred to as the mixed dentition phase, is highly variable. Some second primary molar teeth are replaced by the second premolars as late as 14 years of age.

The simultaneous presence of primary and permanent teeth in the same site during the mixed dentition stage is common and is not a cause for concern.

Dental caries (or decay) remains one of the most common childhood diseases. In Australia just over 60% of 5 year olds and 55% of 12 year olds are decay free; 80% of all decay is experienced by 20% of children. It is therefore important to identify children at high decay risk and specifically target them for prevention (Table 22.3).

Dental decay can occur as soon as teeth erupt. Early childhood caries (ECC) is a particular form of dental decay that is seen in infants as young as 18 months of age. It affects >6% of Australian infants and has a characteristic appearance in which the upper front teeth are affected on their labial (or lip) surfaces. The cariogenic bacteria causing ECC are transmitted from primary caregiver to child, and decay is closely associated with infant feeding habits.

Table 22.1 Eruption sequence of primary dentition (months after birth)

Table 22.2 Eruption sequence of permanent dentition (years of age)

Table 22.3 Dental caries: common risk factors assessable by medical practitioners

| Risk factor | Influence |

| Sugar exposure | Infant feeding habits are very important with frequency of exposure being most relevant. High risk associated with prolonged on-demand night-time feeds and daytime grazing patterns |

| Family oral health history | Poor parental oral health places child at risk of decay as cariogenic bacteria are transmitted from the primary caregiver |

| Fluoride exposure | Exposure to fluoridated water source and the regular use of fluoridated toothpaste are two key factors that reduce caries risk |

| Social and family practices | Low socio-economic status, ethnic and migrant groups have higher levels of dental disease |

| Medical illness | Medically compromised children are more at risk of dental decay and are less likely to receive appropriate treatment |

Prevention

The prevention of dental decay should start as soon as the first tooth erupts. There are four aspects to preventing decay:

Diet

- Minimise the total amount and frequency of intake of sugary foods and drinks.

- Limit sugary snacks to meal times when salivary flow is optimal.

- Minimise intake of drinks with high acidity (e.g. carbonated, fruit and sports drinks), as they cause erosion of the teeth.

- Increase water intake.

- Encourage drinking from feeder cup from the age of 12 months.

- Avoid demand feeding at night time.

Oral hygiene

- Tooth cleaning should commence within 6 months of the eruption of the first tooth.

- Parents should supervise toothbrushing until around 8 years of age.

- Use a toothbrush with a small head for infants and use only a ‘smear’ of toothpaste.

- Under 5 year olds should use a low-fluoride (junior) toothpaste unless they are at increased risk of developing dental caries.

Fluoride

- Fluoride enhances the ability of teeth to resist demineralisation caused by sugar acids.

- Apart from systemic water fluoridation, the most common source of fluoride is toothpaste.

- Most adult toothpastes contain around 1000 ppm.

- Junior toothpastes contain a lower concentrations of fluoride, ∼400 ppm.

- Fluoride supplements in the form of tablets or drops to be chewed and/or swallowed should no longer be used (new guideline, 2006).

Regular dental check-ups

- A child should see a dental professional within 6 months of the eruption of the first tooth.

- The first visit is a ‘well baby’ visit and aimed at providing ‘anticipatory guidance’.

- A child should have a dental check-up at least annually.

- The frequency of dental attendance will vary according to disease risk assessment.

Toothache

- Assess level and nature of pain (e.g. intermittent pain on eating or in response to hot/cold or spontaneous pain at night).

- Provide analgesia (paracetamol should be adequate).

- Refer to dentist for assessment and treatment of the affected tooth.

Dental abscess

Presentation

- History of spontaneous pain, particularly at night; pain may be constant.

- May have recently had fillings.

- Swelling evident intra-orally near teeth.

- Red swollen face, unilateral and often spreading up under the orbit or under the mandible.

- Limited mouth opening.

- Elevated temperature, enlarged lymph nodes and a generally unwell child.

- Tender teeth on side of the swelling.

Investigations

- Orthopantogram (OPG): will show dental pathology, usually decay.

Management

- Consider oral amoxicillin for early infection.

- Admit to hospital if red swollen face, fever and generally unwell.

- I.v. antibiotics (benzylpenicillin in the first instance) and i.v. fluids.

- Extraction of the tooth is almost always indicated.

- Occasionally additional soft tissue drainage is required; however, dental abscesses in young children usually manifest with cellulitis rather than a collection of frank pus.

Traumatic injuries to the facial region can affect the teeth, soft tissues and jaw bones.

History

Consider:

- How did the injury occur?

- Were there any other injuries?

- Time of the injury?

- Where are the teeth or fragments of teeth?

- How much of the tooth is broken off, or how far is the tooth displaced?

- Can the patient bite their teeth together or does the displaced tooth get in the way?

- Are there associated soft tissue (mucosal) injuries?

- Is the avulsed tooth stored in milk?

Locate all teeth or tooth fragments because:

- Most permanent teeth and tooth fragments can be replaced/re-cemented.

- ‘Missing’ teeth may have been intruded (pushed in) rather than knocked out.

- Never replant a primary tooth.

- Injury (particularly intrusion) to a primary incisor can damage the permanent successor, therefore dental review for all injuries is important.

- Associated mucosal injuries may require suturing. Refer to a dentist.

Permanent teeth

Whenever possible an OPG is useful as it allows a full review of the jaws, jaw joints and teeth. A chest radiograph is useful if the tooth or fragments cannot be located. Many injuries can be managed under local anaesthesia, depending on the cooperation of the child and the presence of associated soft tissue or other bony injuries.

- An avulsed permanent tooth is a genuine emergency and should be triaged as such. The longer the tooth is out of the mouth, the worse the prognosis.

- The long-term psychosocial and economical impact on a young person of losing a front tooth should not be underestimated. Appropriate emergency management can make a significant difference to the prognosis of any injured tooth.

Mucosal lacerations

- Check carefully intraorally for degloving injuries (where the gum tissue around the teeth is stripped away from the underlying bone). Unless the lips are retracted, this injury is easily missed. These injuries need suturing under general anaesthesia.

- Many tongue and intraoral lip lacerations do not need suturing and heal well when left.

- Extraoral lacerations, particularly those crossing the vermilion border on to the skin, should be referred to a plastic surgeon.

- In all cases of dental trauma, lift the lips and look in!

Table 22.4 Dental trauma – primary dentition

| Injury | Management |

| No tooth displacement | Non-urgent referral to dentist for review |

| Intrusion – tooth upwards and inwards | Needs dental review within 24 h to accurately locate the tooth. Likely course is re-eruption, otherwise extraction will be required |

| Luxation – tooth palatal or sideways | Needs dental review within 12 h |

| Avulsion – knocked out completely | Extraction is required sooner rather than later Do not replant primary teeth Needs dental review within 24 h |

Table 22.5 Dental trauma – permanent dentition

| Injury | Management |

| Fractures | |

| <1/3 crown | Non-urgent referral to dentist |

| >1/3 crown | Locate fragments, store in milk |

| Needs dental review within 24 h | |

| Some fragments can be reattached to broken teeth | |

| Mobile but not displaced | Soft diet and analgesia |

| Needs dental review within 12 h | |

| May need dental splint | |

| Displacements | All such injuries should be referred to a paediatric dentist within 12 h |

| Intrusions (tooth upwards and inwards) | Locate teeth, using radiographs |

| Tooth may re-erupt or require surgical/orthodontic repositioning | |

| Use gentle finger pressure to reposition teeth, if in doubt leave alone | |

| Luxations (tooth palatal or sideways) | Loose splinting can be achieved using tin foil until patient sees dentist |

| Urgent referral to dentist | |

| Avulsions* (knocked out completely) | Urgent referral to dentist |

| Replace tooth in socket if possible | |

| If not, store in milk at all times |

* An avulsed permanent tooth is a genuine emergency.

Fractures to the jaw bones

- Whenever a jaw fracture is suspected, a maxillofacial surgeon should be called. If teeth are also obviously displaced or lost, a paediatric dentist should also be called.

- An OPG, lateral cephalometric view and/or a variety of occipitomental/anteroposterior radiographic views can be useful in inspecting the facial complex for fractures.

- Tetanus prophylaxis should be considered in any compound fractures opening to mouth or skin, and antibiotics commenced.

Bleeding from the mouth

- Clean the mouth with cold water or saline and remove any debris, blood, tissue etc.

- Identify source of bleeding – usually an extraction socket.

- If child has been bleeding for some time, assess haemodynamic status.

- Bleeding socket:

– Compress the sides of the socket together using finger pressure.

– If child is co-operative place a slightly damp gauze pack over the socket and have child bite down on to it for 20 min. Parents may be asked to assist. Do not pack anything into socket.

– Refer to dentist.

USEFUL RESOURCES

- Spencer AJ. The use of fluorides in Australia: guidelines. Australian Dental Journal 2006; 51(2): 195–199.

- www.aapd.org/pediatricinformation – American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry includes links to Parent Education Brochures and Clinical Guidelines.

- www.ada.org/public/topics/tooth_eruption.asp – The American Dental Association website includes eruption charts and animations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree