When to investigate a murmur

Background

At least 50% of school-age children have a systolic cardiac murmur with no structural or physiological cardiac problem. Chest radiograph (CXR) and electrocardiogram (ECG) are specifi c but not sensitive tests for cardiac disease.

Features of a physiological, functional or ‘innocent’ murmur

History

- Benign family history.

- Asymptomatic.

- Normal growth.

Examination

- Normal general physical examination.

Murmur characteristics

- Continuous murmur, which varies with posture.

- Soft, systolic murmur with:

– Normal second heart sound.

– Separate, audible heart sounds.

– A musical, vibratory quality.

When to refer

A cardiac murmur associated with any of the following requires clinical assessment by a specialist:

History

- Family history of cardiomyopathy or sudden unexplained death.

- Chromosomal disorder.

- Congenital malformation of other organs.

- Maternal diabetes.

- Exertional syncope or unexplained collapse.

- Palpitations.

- Symptoms of cardiac failure.

Examination

- Cyanosis.

- Breathlessness.

- Failure to thrive not clearly due to other causes.

- Unequal pulses.

- Thrill associated with murmur.

Murmur characteristics

- Diastolic murmur.

- Continuous murmur with no postural variation.

- Pan-systolic murmur.

- Loud murmur (amplitude grade 3/6 or greater).

- Murmur harsh or high pitched.

- Murmur heard best at left upper sternal border.

- Abnormal second heart sound.

- Early or mid-systolic click.

Worrying CXR

- Enlarged heart.

- Abnormal cardiac contour.

- Pulmonary plethora.

- ↓ Pulmonary vascular markings.

Worrying ECG

- Abnormal QRS axis.

- Increased voltages.

- Abnormal intervals.

- ST/T wave changes.

The neonate with symptomatic congenital heart disease

Background

- The greatest mortality risk for a neonate with symptomatic congenital heart disease (CHD) is before diagnosis.

- Critically obstructed systemic circulation (e.g. critical aortic stenosis, coarctation and hypo-plastic left heart syndrome) can be indistinguishable from shock due to sepsis.

- CHD should be considered as a differential diagnosis in any unwell neonate, and prostaglandin may be life-saving in duct-dependent lesions.

Clinical syndromes

Clinical syndromes of presentation with symptomatic CHD include:

- Shock due to low cardiac output, often with poor peripheral pulses and acidosis.

- Persistent cyanosis.

- Congestive cardiac failure with respiratory distress and hepatomegaly.

Management

Use of prostaglandin (PGE1)

- There are no congenital cardiac lesions for which PGE1 is absolutely contraindicated.

- Initial dose PGE1 10 ng/kg per min i.v. (= 0.01 mcg/kg per min) then increase to 20–100 ng/kg per min depending on response.

– Aim for saturations in the 80s and improving systemic perfusion if compromised.

- Hypotension and apnoea are the major side effects at higher doses, intubation and ventilation may be required.

- The risk–benefi t is in favour of PGE1 infusion if:

– Patient is in extremis.

– Patient is cyanotic with a murmur.

– Patient has poor peripheral pulses.

Seek early advice from a specialist centre for support to arrange timely transfer for assessment.

Cyanosis in any neonate must be investigated. Consider structural CHD, parenchymal lung disease and persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN).

Clinical syndromes

- Cyanotic CHD is often more likely if there is persistent cyanosis with no respiratory distress and normal CO2 clearance. The presence of a murmur increases the likelihood of a prostaglandin sensitive lesion.

- Parenchymal lung disease is likely if the infant has respiratory distress, elevated PCO2, lung fi eld changes on CXR and a likely cause (e.g. meconium aspiration).

- PPHN is diffi cult to distinguish clinically from cyanotic CHD.

Initial assessment

- Examination: respiratory effort, abnormal pulses and presence of murmur.

- CXR: look at cardiac silhouette, pulmonary vascularity and parenchymal lung disease.

- Arterial blood gases: look for acidosis, PCO2.

- 12-lead ECG: look at axis, rhythm, presence of sinus P waves, QRS complexes.

- Echocardiography: remains the diagnostic test of choice.

- Hyperoxia test:

After 10 min breathing 100% O2, take a right arm, preductal (radial artery) arterial blood gas.

– A PaO2 <70 mmHg will occur with most major cyanotic defects.

– A PaO2 >150 mmHg suggests cyanosis is not due to structural heart disease.

- Trial of prostaglandin (PGE1).

– Will generally result in considerable improvement with duct-dependent CHD.

Seek early advice from a specialist centre.

Heart failure after the neonatal period

Main causes

- Congenital heart defects with pressure or volume overload (±cyanosis).

- Myocardial dysfunction after repair or palliation of heart defects.

- Cardiomyopathies: genetically determined metabolic and muscle disorders, infectious or anthracycline medications.

- Tachyarrhythmias.

- Rheumatic heart disease.

Clinical syndromes

- Infants and young children have non-specific symptoms and signs:

– Dyspnoea, fatigue, feeding difficulties, increased sweating.

– Failure to thrive, poor exercise tolerance.

– Gallop rhythm, hepatomegaly, cardiomegaly.

- Older children may have signs more like those in adults:

– Breathlessness, fatigue, poor exercise tolerance, orthopnoea.

– Nocturnal dyspnoea, venous distension, peripheral oedema.

Management principles

- Seek early advice from a specialist centre.

- Arrange urgent echocardiography for an anatomical and functional diagnosis.

- Oxygen for hypoxia related to pulmonary congestion or respiratory infection.

- Diminish pulmonary and systemic venous congestion:

– Frusemide: 1 mg/kg per dose (8, 12 or 24 hourly).

– Spironolactone (dose by weight): 0–10 kg 6.25 mg/dose oral (12 or 24 hourly), 11– 20 kg 12.5 mg/dose oral (12 or 24 hourly) and 21–40 kg 25 mg/dose oral (12 or 24 hourly).

- Decrease loading conditions:

– Captopril: 0.1–1 mg/kg per dose (max 50 mg) oral 8 hourly.

– Commence ACE inhibitor in hospital to monitor blood pressure.

– Monitor serum potassium if using spironolactone.

- Inotropes for acute, low-output cardiac failure:

– Dobutamine: initially 5 mcg/kg per min i.v.

– Dopamine: initially 5 mcg/kg per min i.v.

– Milrinone: 50 mcg/kg over 10 min i.v. then 0.375–0.75 mcg/kg per min.

- Positive pressure ventilation.

- Treat complications:

– Infection.

– Anaemia.

– Arrhythmia.

– Malnutrition.

Hypercyanotic spells (‘tetralogy spells’)

Severe cyanotic spells are a characteristic feature of tetralogy of fallot (TOF) but may occasionally occur with other cyanotic lesions. The TOF consists of (1) right ventricular hypertrophy, (2) right ventricular outfl ow tract obstruction, (3) ventricular septal defect, with (4) over-riding aorta.

Clinical presentation and background

- Severe cyanosis with agitation and breathlessness.

- Often precipitated by exertion, feeding or crying, but can be spontaneous.

- Mechanism probably involves increased right ventricular outfl ow tract contractility, peripheral vasodilatation and hyperventilation.

- The right ventricular outfl ow tract murmur becomes softer and may become inaudible.

- Most episodes are self-limiting, lasting 15–30 min, but can be prolonged or result in loss of consciousness.

Management

Initial

- Avoid exacerbating distress.

- Try to console the child by cradling, soothing or nursing in a knee–chest position.

- Give high-fl ow oxygen via mask or head box.

- Morphine 0.2 mg/kg i.m. may help in severe cases.

- Continuous ECG and oxygen saturation monitoring, frequent BP monitoring.

- Correct any underlying cause, e.g. arrhythmia, hypothermia, hypoglycaemia.

If prolonged

- I.v. fl uids: 0.9% normal saline 10 mL/kg bolus followed by maintenance fl uids.

- Correct acidosis: sodium bicarbonate 1–2 mmol/kg i.v.

- Beta-blocking drugs: i.v. esmolol 0.5 mg/kg over 1 min, then 50–200 mcg/kg per min for up to 48 h.

- Intubation and positive pressure ventilation may be required in extreme cases.

Longer term

- In most cases, hypercyanotic spells are an indication for palliative or corrective surgery.

- Oral propranolol may be given prophylactically to prevent spells in a child awaiting surgery.

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

Seek urgent specialist advice if any tachycardia is broad complex or irregular, or fails to respond to the management.

Definition

Supraventricular tachycardia is usually a regular, narrow complex tachycardia, with heart rate 160–300 beats/min.

Differential diagnosis

Sinus tachycardia up to 230 beats/min may occur in the neonate with:

- Hypovolaemia.

- Hypoventilation.

- Pain.

- Fever.

- Pulmonary hypertension.

Note: Ventricular tachycardia in the neonate can have a relatively narrow QRS complex.

Clinical features

- In utero: may cause hydrops.

- Infancy: irritability, pallor, poor feeding and dyspnoea secondary to congestive cardiac failure.

- Older children: palpitations, chest discomfort.

- Hypotension may be present at any age.

Initial management

- Physical examination:

– Pulse, BP, murmur.

– Signs of cardiac failure (tachypnoea, increased work of breathing, hepatomegaly).

- 12-lead ECG to confirm a narrow-complex tachycardia.

Patient normotensive and well perfused

Vagal manoeuvres

- Infant or young child:

– Ice water in bag or icepack to face for a few seconds only.

– Oropharyngeal suctioning.

– Gag with spatula.

- Older child:

– Valsalva manoeuvre (e.g. forced blow through a blocked straw).

I.v. adenosine

- Full resuscitation facilities should be available.

- I.v. access in a large, proximal vein.

- Record a continuous ECG rhythm strip throughout administration, to monitor the pattern of reversal.

- Begin with adenosine 0.1 mg/kg as an initial bolus (max 6 mg):

– Repeat doses can be given at 2 min intervals increasing by 0.05 mg/kg each dose to maximum 0.3 mg/kg (18 mg).

- Dilute small doses of adenosine with saline to allow rapid infusion.

- Give adenosine quickly, followed immediately by a 5 mL normal saline flush.

- Check patient’s vital signs.

– Rapid re-initiation of the tachycardia may occur due to premature atrial contractions, a repeated and often lower dose may be successful in this case.

- Side effects of adenosine: facial fl ush, chest pain, bronchospasm.

Patient shocked (hypotensive, poor perfusion, impaired mental state)

- Ensure child is given oxygen and has i.v. access.

- The airway should be managed by experienced staff.

- Administer midazolam 0.2 mg/kg (max 10 mg) i.v. to minimise awareness and fentanyl 1–2 mcg/kg (max 50–100 mcg) if rapidly available for analgesia.

- D/C revert using a synchronised shock of 1 J/kg.

Subsequent management

After stabilisation of SVT, specialist review is required for:

- 12 lead ECG in sinus rhythm (pre-excitation and other abnormality).

- Echocardiogram (structural associations of atrioventricular re-entry SVT, e.g. Ebstein’s anomaly, cardiomyopathy).

- 24 h Holter monitor (intermittent pre-excitation and initiating triggers such as premature atrial contractions).

- Decisions regarding prophylaxis, electrophysiological study.

For infective endocarditis to develop, two independent events are normally required: a damaged area of endothelium and a bacteraemia.

Presentation

- Usually insidious and non-specific presentation.

- Often suggestive of intercurrent viral illness.

- Fever, anorexia, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, general malaise.

– Splenomegaly, splinter haemorrhages, petechiae and other peripheral stigmata are rarely seen in children but do occur. Careful repeated examination for these signs is necessary as they may not develop until several days into the illness.

Diagnosis

- Suspect endocarditis in any patient with a structural cardiac anomaly and prolonged fever, or who develops fever and a new murmur.

- Multiple blood cultures (at least three) from separate sites and at different times, before antibiotic administration.

- Full blood count.

- ESR and CRP.

- Echocardiogram.

– Transoesophageal echo may be more sensitive than transthoracic echo but is often non-contributory in young children with good imaging through a relatively thin chest wall.

– The sensitivity and specificity of echo for endocarditis are limited, thus a normal echocardiogram does not exclude endocarditis.

Management

- Admission to hospital.

- Commence empiric antibiotics which should be chosen to cover endocarditis as well as other potentially serious causes for the presenting illness.

– Native valve/homograft: benzylpenicillin 60 mg/kg (max. 2 g) i.v. 6 hourly plus fl ucloxacillin 50 mg/kg (max. 2 g) i.v. 6 hourly plus gentamicin 2.5 mg/kg (max. 240 mg, synergistic dose) i.v. 8 hourly.

– Prosthetic valve: vancomycin 15 mg/kg (max. 500 mg) i.v. 6 hourly plus gentamicin 2.5 mg/kg (max. 240 mg, synergistic dose) i.v. 8 hourly.

- Prolonged antibiotic therapy is required. Specialist consultation is recommended to tailor the antibiotic regimen to individual patients and pathogens.

- Close monitoring of clinical and cardiovascular status including serial echo, blood cultures and infl ammatory markers.

- Close monitoring for evidence of other embolic phenomena.

Endocarditis prophylaxis

- Children at risk should establish and maintain the best possible oral health to reduce potential sources of bacteraemia.

- Single dose antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for children at risk, undergoing procedures likely to cause a bacteraemia (see Table 21.1).

- Recommended prophylaxis is with amoxicillin 50 mg/kg oral 1 h preoperatively (max. 2 g).

- If unable to take oral medication, give amoxicillin 50 mg/kg i.v. at induction (max. 2 g).

- For penicillin-allergic patients, see Antimicrobial guidelines, page 603.

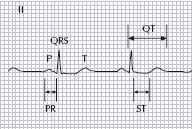

ECG interpretation should include a systematic assessment of rate, rhythm, axis, P waves, QRS, ST segments, T waves and intervals; PR, QT and QTc.

A normal ECG should have an appropriate rate for age and a P-wave, which should be upright in leads I and aVF, preceding each QRS complex (see Fig. 21.1).

Table 21.1 Indications for antibiotic prophylaxis for endocarditis

| High-risk cardiac conditions | High-risk procedures | Children not at risk |

| • Cyanotic defects | • Dental procedures (involving manipulation of gingival tissues, periapical region of teeth or perforation of oral mucosa) | • Confi rmed ‘innocent’ or physiologic murmurs |

| • Prosthetic valves | • Invasive procedure of respiratory tract (involving breach of respiratory mucosa) | • Non-structural problems (e.g. arrhythmia) |

| • Conduits/shunts | • Procedures on infected skin, skin structures or musculoskeletal tissue | • Previous Kawasaki disease without valvular dysfunction |

| • Previous endocarditis | • Genitourinary or gastrointestinal procedures |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree