Poisoning

Background

Poisoning during childhood occurs mainly among 1–3 year-olds and tends to follow the ingestion of one of a wide variety of agents improperly stored in the home. It should be considered in any child presenting with symptoms that cannot be explained, such as altered conscious state, tachy- or bradycardia and unusual behaviour.

Other circumstances of poisoning are iatrogenic (particularly in infants) and the deliberate self-administration of substances by older children for their recreational use or to manipulate their psychosocial environments. Increasingly, the intention is suicidal and this should be considered, even in young children. See also chapter 15, Adolescent health and chapter 16, Child psychiatry.

Although poisoning in childhood is frequently minor in severity and mortality is low, serious illness may be caused by prescription and over-the-counter drugs and non-pharmaceutical products, including complementary medications (see p. 546, chapter 39, Prescribing for children).

Prevention

- Action should be taken according to the circumstance of poisoning to prevent recurrence.

- Parents should be encouraged to store all medicines in childproof cabinets and toxic substances in places inaccessible to young children.

- Urgent psychosocial help should be organised for children who have poisoned themselves intentionally.

- Steps should be taken to ensure that iatrogenic poisoning is not repeated. Institutions should develop programmes to detect and prevent drug errors.

General management

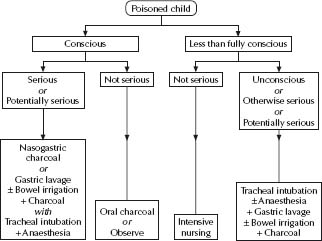

See Fig. 2.1. The principles of management for all poisonings are:

- Resuscitate the patient and remove the poison if indicated.

- Administer an antidote if one exists (see Table 2.1).

In Australia, call Poisons Information on 13 11 26 – a 24-hour nationwide service.

Recovery is expected in the majority of cases if vital functions are preserved and the complications of poisoning and its management are avoided.

A decision to remove the poison from the body should be dependent on the severity of the poisoning and the likelihood of success in removing the poison without further endangering the patient. Most poisonings in childhood are minor and observation alone or noninvasive treatment is indicated.

The severity of poisoning may be assessed by the:

- Established and expected effects.

- Quantity of the poison(s).

- Preparation of the poison.

- Interval since exposure.

Removal from the body usually involves gastrointestinal decontamination but occasionally other methods, such as dialysis, exchange transfusion, charcoal haemoperfusion, plasmapheresis or haemofiltration are required.

Gastrointestinal decontamination

If the conscious state is depressed, all methods of gastrointestinal decontamination carry a substantial risk of aspiration pneumonitis, even if the patient is intubated. Hence, the most important factor determining the technique of decontamination is the conscious state. A guideline for the general management of poisoning using these techniques according to severity of poisoning is shown in Fig. 2.1. The most commonly used method is with activated charcoal, with gastric lavage and whole-bowel irrigation having limited roles. There is no role for induced emesis in the hospital setting.

Table 2.1 Antidotes to poisons

| Poison | Antidotes and doses | Comments |

| Amphetamines | Esmolol 0.5 mg/kg i.v. over 1 min, then 25–200 mcg/kg per min i.v. | Treatment for tachyarrhythmia. |

| Labetalol 0.15–0.3 mg/kg i.v. or phentolamine 0.05–0.1 mg/kg i.v. every 10 min. | Treatment for hypertension. | |

| Benzodiazepines | Flumazenil 5 mcg/kg i.v. repeated at 1 min then 2–10 mcg/kg per h by i.v. infusion. | Specific antagonist at receptor. |

| Titrate to effect. Caution: may precipitate convulsions or arrhythmia in multi-drug ingestion, especially with tricyclics. | ||

| Beta blocker | Glucagon 7 mcg/kg i.v. then 2–7 mcg/kg per min i.v. infusion. | Stimulates non-catecholamine cAMP production. Preferred antidote. |

| Isoprenaline 0.05–2 mcg/kg per min i.v. Beware b2 hypotension. Noradrenaline 0.05–0.5 mcg/kg per min i.v. | ||

| Calcium blocke | Calcium chloride 20 mg (0.2 mL of 10%)/kg i.v. | |

| Carbon monoxide | Oxygen 100% | Hyperbaric oxygen may be required. |

| Cyanide | Dicobalt edetate 7.5 mg/kg (max 300 mg i.v.) over 1 min, then repeat at 5 min if no effect. | Chelates. Give 50 mL 50% glucose after each dose. |

| Sodium nitrite 3% i.v. (0.33 mL/kg over 4 min), then sodium thiosulphate 25% i.v. 1.65 mL/kg (max 50 mL) at 3–5 mL/min. | Nitrites form methaemoglobin-cyanide complex (beware excess methaemoglobinaemia – restrict to <20%) Thiosulphate forms non-toxic thiocyanate from methaemoglobin-cyanide. | |

| Digoxin | Digoxin Fab. Dose: acute ingestion 1 vial/2.5 tablet (0.25 mg); in steady state vials = serum digoxin (ng/mL) × BW (kg)/100. | |

| Ergotamine | Sodium nitroprusside infusion 0.5–5 mcg/kg per min. | Treats vasoconstriction. Monitor BP continuously. |

| Heparin 100 units/kg i.v. then 10–30 units/kg i.v. per h according to clotting. | Treatment of coagulopathy. | |

| Lead | If symptomatic or blood lead >2.9 μmol/L dimercaprol (BAL) 75 mg/m2 i.m. 4-hourly 6 doses then calcium disodium edetate (EDTA) 1500 mg/m2 i.v. over 5 days. If asymptomatic and blood lead 2.18–2.9 μmol/L infuse calcium disodium edetate 1000 mg/m2 per day for 5 days. | |

| Heparin | Protamine 1 mg/100 units heparin i.v. | Heparin half-life 1–2 h. |

| Iron | Desferrioxamine 15 mg/kg per h 12–24 h if serum iron >90 μmol/L or >63 μmol/L and symptomatic. | Beware anaphylaxis. |

| Methanol, ethyleneglycol, glycol ethers | Ethanol, infuse loading dose 10 mL/kg 10% diluted in glucose 5% i.v. and then 0.15 mL/kg per h to maintain blood level at 0.1% (100 mg/dL). | |

| Methaemoglobin e.g. 2° to drug treatment | Methylene blue 1–2 mg/kg i.v. over several min. | |

| Opiates | Naloxone 0.01–0.1 mg/kg i.v., then 0.01 mg/kg per h as needed. | |

| Organophosphates and carbamates | Atropine 20–50 mcg/kg i.v. every 15 min until secretions dry. Pralidoxime 25 mg/kg i.v. over 15–30 min, then 10–20 mg/kg per h for 18 h or more. Not for carbamates. | Restores cholinesterase. |

| Paracetamol | N-acetylcysteine. I.v.; 150 mg/kg over 60 min, then 10 mg/kg per h for 20–72 h. Oral; 140 mg/kg then 17 doses of 70 mg/kg 4 hourly (total 1330 mg/kg over 68 h). | Give for >72 h if still encephalopathic. |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Sodium bicarbonate i.v. 1 mmol/kg to maintain blood pH >7.45. |

Activated charcoal

Activated charcoal is more efficacious than induced emesis or gastric lavage and is currently regarded as a ‘universal antidote’. It adsorbs most poisons but not metals, corrosives or pesticides. Like other techniques, however, it is contraindicated in the less than fully conscious patient or if ileus is present. If aspirated, charcoal may cause fatal bronchiolitis obliterans. Constipation is relatively common. Addition of a laxative decreases transit time through the gut but does not improve efficacy in preventing drug absorption. It may also upset fluid and electrolyte balance. The initial dose is 1–2 g/kg. Repeated doses of activated charcoal enhance elimination of many drugs, particularly slow-release preparations. A suitable regimen is 0.25 g/kg per hour for 12–24 h.

Gastric lavage

Although gastric lavage appears to be a logical therapy for ingested poisons, it has a limited place in management. Problems include

- Poor efficacy in preventing absorption when done >60 min after ingestion.

- Risk of aspiration pneumonitis in the less than fully conscious patient and to a lesser extent in the conscious child.

- In the conscious young child, it is psychologically traumatic and difficult to do.

- If it is undertaken, care should be taken to avoid water intoxication and intrabronchial instillation of lavage fluid.

- Gastric lavage is contraindicated after ingestion of corrosives, hydrocarbons or petrochemicals.

- Gastric lavage is indicated in serious poisoning when a child is already intubated for airway protection and ventilation. The child should be in the lateral position during lavage. If potentially serious effects are expected, gastric lavage should only be done after rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia and tracheal intubation.

Whole bowel irrigation

Whole bowel irrigation is done with a solution of polyethylene glycol (30 mL/kg per hour for 4–8 h) and electrolytes administered by nasogastric tube. It is useful in delayed presentations and for the management of poisoning by slow-release drug preparations, substances not adsorbed by activated charcoal (e.g. iron) or substances which are irretrievable by gastric lavage.

Induced vomiting

Syrup of ipecacuanha is no longer routinely recommended. Its usefulness in the hospital setting is extremely limited – perhaps only to a case of serious poisoning presenting very early after ingestion when no other effective treatment is possible. It was previously used as a fi rst aid measure in the home, but it does not reliably empty the stomach and is contraindicated where conscious state is impaired (risk of aspiration pneumonitis) and when the ingested substance is corrosive, hydrocarbon or petrochemical.

Poisoning with unknown or multiple agents

- Suspect poisoning on presentation with convulsions, depression of the conscious state, hypoventilation, hypotension or an illness that is not otherwise readily explained. A urinary drug screen may be useful for diagnosis.

- Multiple poisons may have been ingested. Determine blood levels if there is any possibility of ingestion of paracetamol, iron, salicylate, theophylline, methanol, digoxin or lithium. Blood levels may influence clinical management.

- Contact the Poisons Information hotline for advice; see p. 14.

Individual poisons

Thousands of poisons exist. The most common serious poisons in young children presenting to the Royal Children’s Hospital have been paracetamol, rodenticides, eucalyptus oil, benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants and theophylline.

Only the most common serious poisonings, or poisonings peculiar to children are considered here briefly. Some have antidotes (see Table 2.1). The general principles of management apply to all individual poisons (see Fig. 2.1). Details of effects of specific poisons and suggested management should be obtained from a Poisons Information Centre and from appropriate, up-to-date references.

Consider the possibility of intentional drug ingestion. These children are often at ‘high risk’ for multiple psychological and social reasons. See also chapter 15, Adolescent health.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen)

Paracetamol is the most common pharmaceutical poisoning.

Effects

The liver metabolises it to a toxic product, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, which causes hepatic necrosis unless neutralised by the hepatic antioxidant, glutathione. Multi-organ failure and death may occur after 3–4 days if the ingested quantity exceeds 150 mg/kg or with smaller amounts with prior hepatic dysfunction, alcohol or anticonvulsants. Early symptoms are anorexia, nausea and vomiting.

Specific Management

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an effective antidote if given before hepatic necrosis occurs. Its use is associated with adverse reactions (e.g. rash, bronchospasm and hypotension) that occur more frequently when administered i.v. If reactions occur, cease NAC temporarily and give promethazine 0.2–0.5 mg/kg i.v. (max. 10–25 mg) and recommence the NAC infusion at a reduced rate.

Since the outcome is related to serum levels of paracetamol measured 4–20 h after ingestion, a decision to administer NAC after a single overdose may be made according to time-related plasma levels. Administer if the level exceeds 1000 μmol/L at 4 h, 500 at 8 h, 200 at 12 h, 80 at 16 h, or 40 at 20 h (μmol/L × 0.15 =μg/mL).

- I.v. NAC: 150 mg/kg in 5 mL/kg of glucose 5% over 60 min, then 10 mg/kg per hour for 20 h or longer if the child is encephalopathic, or presentation is 10–36 h after ingestion or

- Oral NAC: 140 mg/kg, then 17 doses of 70 mg/kg (4 hourly).

- Note:

- Serum levels >18 h after a single ingestion are unreliable predictors of risk.

- These recommendations do not apply to multiple smaller ingestions (seek expert advice).

- Presentation <1 h after significant ingestion may be treated with gastric lavage (see p. 18).

- Monitor liver function tests and serum potassium.

Iron

Small quantities (<20 mg/kg) of elemental iron may be toxic. This is usually ingested as iron tablets/capsules, mixtures or multivitamin preparations.

Effects

- Immediate: Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and possible gastric erosion.

- At 6–24 h: Hypotension, hypovolaemia and metabolic acidosis.

- At 12–24 h: Multi-organ failure – gastrointestinal (ileus, gastric erosion), CNS, cardiovascular, hepatic and renal.

- At 4–6 weeks: Pyloric stenosis.

Specific Management

- Serum iron level (mcg/dL × 0.1791 =μmol/L). Note: Absorption may be slow.

- Abdominal radiograph may reveal the quantity ingested.

- Whole bowel irrigation (not if ileus, obstruction or erosion are present). Activated charcoal is ineffective.

- Infusion of desferrioxamine no faster than 15 mg/kg per hour for 12–24 h is indicated if: – Patient is clinically hypotensive or has depressed consciousness.

– >60 mg/kg elemental iron has been ingested.

– Iron level is >90 μmol/L.

– Iron level is >63 μmol/L and patient is symptomatic.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Sudden death may occur.

Effects

The life-threatening effects are:

- CNS depression: coma, convulsions.

- Non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema.

- Cardiac depression: hypocontractility, hypotension and sudden dysrhythmias (conduction blocks and ventricular ectopy, including tachycardia/fibrillation).

Specific Management

- ECG monitoring: assess heart rate, QRS duration and QT interval.

- Alkalisation of blood to pH 7.45–7.50 with sodium bicarbonate infusion or hyperventilation, or both.

- Anticonvulsant therapy with diazepam 0.1–0.4 mg/kg (max 10–20 mg).

- Antidysrhythmia therapy: give phenytoin slowly (over 30 min). Beware of hypotension.

- Treatment of hypotension with an alpha-agonist (noradrenaline 0.01–1 mcg/kg per min). Avoid beta-agonists and drugs with mixed alpha and beta actions.

- Treatment of ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation with DC shock, amiodarone (5 mg/kg i.v.) or lignocaine (lidocaine) (1 mg/kg, then 10–50 mcg/kg per min) and a beta-blocker.

- Treatment of torsade de pointes with DC shock, magnesium sulfate (0.1–0.2 mmol/kg i.v.) or lignocaine (lidocaine) as above.

Salicylates

Toxicity is expected if >150 mg/kg is ingested.

Effects

- Coma, hyperpyrexia and respiratory alkalosis followed by metabolic acidosis.

- Cardiac depression, pulmonary oedema and hypotension.

- Hepatic encephalopathy (Reye syndrome) with chronic use.

Specific Management

- Serum salicylate level, blood glucose, serum potassium and blood pH.

- Correction of dehydration.

- Correction of acidosis and maintenance of urine pH >7.5 (with sodium bicarbonate) and correction of hypokalaemia.

- Haemodialysis/haemoperfusion if the serum level is >25 mmol/L (mcg/mL × 0.0724 = μmol/L).

Theophylline

Toxicity is related to serum levels and may be delayed with slow-release preparations.

Effects

- Gastrointestinal: nausea, protracted vomiting, abdominal pain.

- Metabolic:

– Hypokalaemia due to migration into cells, diuresis and vomiting.

– Metabolic acidosis.

– Hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinaemia and hypomagnesaemia.

- CNS: seizures, agitation, coma (uncommon).

- Cardiovascular: atrial and ventricular ectopy, hypotension.

Specific Management

- Prolonged observation if a slow-release preparation is ingested.

- Serum level (anticipate seizures at approximately 300 μmol/L and the need for charcoal haemoperfusion or plasmapheresis at approximately 550 μmol/L, or less if there is protracted vomiting).

- Anti-emetic therapy with metoclopramide 0.15 mg/kg (max 10–15 mg) i.v. 6 hourly.

- ECG monitoring. Beware of early hypokalaemia and late hyperkalaemia when potassium re-enters the blood.

Eucalyptus and essential oils

Effects

- Initial coughing, choking.

- Rapid onset (30 min, occasionally delayed) CNS depression (convulsions and meiosis are rare).

- Vomiting and subsequent aspiration pneumonitis.

Specific Management

- Exclude pneumonitis (perform chest radiograph and measure oxygenation).

Amphetamines

Effects

- Amphetamine and derivatives, e.g. methamphetamine (‘ice’) and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy), are strong stimulants of the CNS, but may also induce convulsions, hyperthermia (with secondary coagulopathy and rhabdomyolysis), hypertension, cardiovascular collapse and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Specific Management

Treatment is largely supportive and may include sedatives (benzodiazepine), anticonvulsants, beta- and alpha-blockade, dantrolene, mechanical ventilation, inotropic and renal support.

Petroleum distillates

Inhaling the fumes of petrol, kerosene, lighter fluid, lamp oils, solvents and mineral spirits is often referred to as ‘chroming’ or ‘sniffi ng.’ There are significant social and cognitive effects of long-term abuse and these children are at high risk because of multiple psychosocial reasons. See also chapter 15, Adolescent health.

Effects

- CNS obtundation, convulsions, vomiting or hepatorenal toxicity.

Specific Management

- Exclude pneumonitis (perform chest radiograph and measure oxygenation).

Button or disc batteries

- Ingestion may cause electrolysis, corrosion, the release of toxins or pressure effects.

- Impaction in the oesophagus is an emergency – it may cause perforation or an oesophagotracheal fistula and must be removed endoscopically as soon as possible. Surgical follow-up is essential.

Caustic substances

- Automatic machine dishwashing detergents, caustic soda, drain cleaners are strong alkalis and cause burns to the gastrointestinal tract when ingested.

- Significant oesophageal damage may occur in absence of proximal injury.

- Arrange surgical oesophagoscopy and follow-up.

The Australian Venom Research Unit (www.avru.org) provides a 24-hour advisory service on 1300 760 451.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree