Allergic diseases

Allergic disease is an increasingly common problem in the community, affecting up to 40% of children. The allergic conditions include asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis and allergies to food, insects or drugs. Children who have allergic diseases are often atopic; that is, they produce IgE antibodies to common allergens such as house dust mite, animal dander, pollens and foods. The presence of IgE antibodies (i.e. sensitisation) to these allergens does not necessarily cause disease; however, exposure to an allergen to which a patient is sensitised may exacerbate or precipitate symptoms (e.g. inhalant, food, insect or drug allergy).

Allergy tests include skin-prick tests (SPT) and radioallergosorbent tests (RAST). Both detect specific IgE antibodies against allergens. SPT and RAST are available for numerous allergens. Testing should be individualised for each clinical situation and is used to confirm suspected allergy. Testing to ‘routine’ allergen panels is not recommended.

Skin-prick tests

- Preferred because they are highly sensitive, inexpensive, simple and rapid.

- Age is not a contraindication to skin-prick testing. Skin-prick testing can be done from early infancy, but a negative skin test in infancy does not preclude the later development of sensitisation.

Limitations

- SPTs have a poor positive predictive value (<50%) for the presence of clinical allergy in the absence of a previous clinical reaction. The finding of a positive SPT to a food in this context does not necessarily indicate presence of clinical allergy.

- May be affected by medications. Antihistamines should be withheld for 2–4 days. Inhaled â2-agonists, oral theophylline and corticosteroids do not interfere with SPTs.

- Dermatographism may complicate the interpretation of SPTs. Saline and histamine controls must be done.

Indications

- Evaluation of suspected IgE-mediated food reactions. A negative SPT almost eliminates the possibility that a food will induce an IgE-mediated immediate reaction. A positive SPT must be correlated with the history. When there is a clear history of reaction to a specific food, a positive SPT confirms food allergy. If the history is uncertain, a positive test only indicates the possibility of food allergy and a cautious supervised inpatient food challenge in a specialist centre is required to confirm the presence or absence of allergy. SPT should not be routinely used to screen for the presence of food allergy. If there is a high suspicion of food allergy, refer the child to a specialist.

- Skin-prick testing to the relevant environmental allergens can identify major allergic factors that may exacerbate or contribute to symptoms and can guide the application of appropriate environmental modification. Consider performing in:

– Patients with asthma or rhinitis who require maintenance steroid therapy to control symptoms, including patients with frequent episodic asthma.

– Patients with moderate or severe eczema despite appropriate medical therapy.

Radioallergosorbent tests

- Have reduced sensitivity, are more expensive and have a slower turnaround time.

- Are useful alternatives to SPTs if there is dermatographism, widespread skin disease, or if antihistamines cannot be discontinued.

- May be useful in the primary care setting as initial limited investigation to confirm a suspected, simple allergy (e.g. confirmation of IgE-mediated food allergy to cow’s milk, egg or peanut; or assessment for HDM, pet dander or pollen sensitisation in asthma or allergic rhinitis).

Interpretation of SPT and RAST

- A positive SPT or RAST only identif es the presence of specific IgE against an allergen (i.e. sensitisation).

- A positive test does not prove that an allergic disease exists, nor does it necessarily predict that the patient will develop symptoms on exposure to that substance. For example, only 50% of individuals with a positive SPT to a food allergen will develop symptoms when exposed to that food.

- In general, the larger the SPT and/or the higher the RAST result, the greater the likelihood of clinical allergy.

In vivo challenges

- In vivo challenges are primarily used for diagnosis of food allergy and the evaluation of antibiotic reactions.

- They may also be used to assess the development of tolerance to foods.

- They are highly specialised procedures that should only be done in specialist centres with facilities for the early identif cation and management of allergic reactions.

- They are usually not done if there is a clear history of food allergy or anaphylaxis and the trigger has been identif ed.

- Cautious inpatient challenge is used to test the clinical relevance of a positive SPT where the history is unclear.

- In these circumstances, less than half of the patients with a positive SPT to a food will react to the food during a challenge. In general the larger the SPT size the greater the likelihood of clinical allergy. However, the size of a SPT does not correlate with the severity of reaction.

- Diagnosis of delayed non-IgE-mediated reaction to foods requires a formal food challenge, as there are no skin-prick or blood tests for this type of food reaction.

Allergic rhinitis refers to nasal symptoms of paroxysmal sneezing, itching, congestion and rhinorrhoea caused by sensitivity to environmental allergens. It can have a major impact on the quality of life and school performance, and appropriate recognition and treatment is important. This condition is commonly unrecognised.

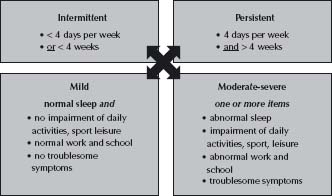

Traditionally, allergic rhinitis has been classified as perennial (symptoms throughout the year, commonly due to HDM sensitisation), seasonal (symptoms occurring in a particular season, i.e. seasonal rhinitis/hay fever) or related to a specific allergen (e.g. cats or horses). More recently an alternative classification has been proposed which describes symptoms as ‘persistent’ (symptoms for >4 days a week and >4 weeks a year) or ‘intermittent’ (symptoms <4 days a week or <4 weeks a year), and as mild, moderate or severe (Fig. 19.1). Both classification systems may be used in combination.

Diagnosis requires the demonstration of an allergic basis for symptoms. Other causes of rhinitis should be considered: nonallergic rhinitis with eosinophilia syndrome (NARES), infective rhinitis, vasomotor rhinitis, hormonal rhinitis or rhinitis medicamentosa (rhinitis induced by excessive use of topical decongestants).

Fig. 19.1 Classification of allergic rhinitis. (Reproduced with permission from ARIA Workshop Executive Summary. (2002) Allergy. 57; 2002: 841–855.)

Perennial allergic rhinitis

- Can occur at any age and is more common than seasonal rhinitis in preschool and primary school children.

- Sneezing and congestion are prominent especially on waking in the morning. There may be significant nasal obstruction and snoring at night.

- House dust mite is the major allergen involved but concurrent sensitivity to pollens is also common.

- Consider the possibility of perennial allergic rhinitis in any atopic child – this diagnosis is frequently missed.

- Any patient with allergic rhinitis and significant obstructive symptoms is at risk of obstructive sleep apnoea.

Seasonal allergic rhinitis

- More frequent in teenagers and young adults.

- Seasonal sneezing, itching and rhinorrhoea are prominent. Nasal symptoms are frequently associated with symptoms of itchy, red and watery eyes.

- Symptoms occur in the relevant pollen season.

- In general, trees pollinate in early spring, grasses in the late spring and summer, and weeds in the summer and autumn, although there is some overlap. Rye grass is the commonest provoking antigen in Australia, but multiple sensitivities to tree, grass and weed pollens are also seen.

Examination

No examination is complete until you have looked in the nose!

- Assess the nasal mucosa and nasal airflow.

- Pale oedematous mucosa and swollen turbinates indicate ongoing rhinitis. In seasonal rhinitis, examination may be normal outside the relevant pollen season.

Management

- Topical corticosteroid nasal sprays are the treatment of choice for both allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. The presence of congestion, nasal drainage or persistent symptoms (>4 days a week and >4 weeks per year) warrants treatment with topical corticosteroid nasal sprays. In general, full strength (prescription requiring) forms of nasal corticosteroid are recommended where there is significant rhinitis. Refer to Table 19.1.

- Continuous topical corticosteroid therapy for allergic rhinitis has not been shown to cause suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. In seasonal rhinitis, commence treatment 1 month prior to the relevant pollen season and continue over the symptomatic period.

- Topical sodium cromoglicate is generally not effective.

- Topical anti-inflammatory treatment must be taken regularly for benefit. Improvement may not be apparent for 3–4 weeks and an initial course of treatment should last for 2–3 months.

- Allergen avoidance measures should be considered for patients using topical anti-inflammatory therapy. These are most feasible with certain allergen triggers (e.g. pets in animal dander sensitivity, house dust mite allergen in perennial rhinitis with dust mite sensitivity). Dust mite reduction involves washing bedding in hot water weekly, removing soft toys and soft furnishings from the bedroom, vacuuming carpet and damp-dusting hard surfaces (including hard flooring) weekly and using allergen-impermeable covers for the mattress, pillow and doona or duvet. Avoidance of grass pollens is generally not possible.

- Antihistamines are not helpful in relieving nasal obstruction and are not indicated as first line treatment for significant rhinitis. Antihistamines may be used for intermittent symptoms (<4 days per week or <4 weeks a year) in the absence of congestion or signifi-cant rhinorrhoea (see Table 19.2). They may also be useful for control of break-through sneezing, itching or rhinorrhoea while on topical corticosteroid therapy or prophylactically before allergen exposure in allergen-specific rhinoconjunctivitis (e.g. cats or horses). Second-generation less-sedating antihistamines (loratadine and cetirizine) are well tolerated. Terfenadine and astemizole should be avoided as they may cause cardiac arrhythmia when taken with other medications.

Table 19.1 Nasal corticosteroids

| Nasal corticosteroid type | Brand name | Dose |

| Prescription only | ||

| Budesonide | Rhinocort | 64 mcg |

| Mometasone | Nasonex | 50 mcg |

| Over-the-counter | ||

| Budesonide | Rhinocort aqueous | 32 mcg |

| Fluticasone propionate | Beconase Allergy & Hayfever 24 | 50 mcg |

Table 19.2 Antihistamines

| Antihistamine type | Brand name | Dose |

| Less sedating | ||

| Loratadine | Claratyne (10 mg tablet, 1 mg/mL syrup) | 1–2 years: 2.5 mg/dose once daily |

| 3–6 years: 5 mg/dose once daily | ||

| Lorastyne (10 mg tablet) | >6 years & adults: 30 mg/dose once daily | |

| Fexofenadine | Telfast (30 mg, 60 mg, 120 mg, 180 mg tablets) | >6 years: 30 mg/dose twice a day |

| Adults: 60 mg/dose twice a day | ||

| Cetirizine | Zyrtec (10 mg tablet, 1 mg/mL syrup, 10 mg/ mL drops = 0.5 mg/drop) | >1 years: 0.125 mg/kg/dose twice a daily |

| 2–5 years: 2.5–5 mg/day in 2 doses | ||

| 6–12 years: 5–10 mg/day in 1–2 doses | ||

| Adults: 10–20 mg/day in 1–2 doses | ||

| Sedating antihistamine | ||

| Trimeprazine | Vallergan (1.5 mg/mL syrup) | >2 years (allergy): 0.1–0.25 mg/kg/dose 6-hourly |

| Vallergan Forte (6 mg/mL syrup) | (Sedation) dose: 1–2 mg/kg nocte | |

| Adults: 10 mg/dose 3 times a day (max 100 mg/day) |

Allergic conjunctivitis is commonly associated with allergic rhinitis.

- Occasionally eye symptoms occur in isolation.

- Red, watery, itchy eyes.

- May be persistent or intermittent.

Management

- Eye toilet with normal saline to flush out allergen, cool compresses.

- Oral antihistamine may be adequate.

- Topical therapies, i.e. eye drops such as antihistamine, combination antihistamine/mast cell stabilisers (e.g. Patanol).

- Occasionally symptoms may be severe and warrant topical corticosteroid therapy, but this should only be prescribed with caution and in consultation with an allergy specialist or ophthalmologist.

Food allergy is commonest in infancy; affecting 6–8% of children. More than 90% of food allergy reactions are caused by eight food groups – milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanut, tree nuts, fish and shellfish. Most food allergies resolve by 5 years of age. The exceptions are peanut, tree nut and shellfish allergies, which frequently persist and account for most food allergies in adults (affecting ∼2% of the adult population).

Allergic reactions to foods fall into two broad groups: IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated reactions.

IgE-mediated food reactions

- Are common.

- Occur within 30–60 min of food ingestion.

- Typically occur in young infants and frequently resolve by the age of 3–5 years.

- Are most commonly triggered by milk, eggs and peanuts.

- Common symptoms are angioedema (usually facial), urticaria and vomiting immediately after the ingestion of the food.

- More severe reactions (anaphylaxis) involve the respiratory tract (stridor, wheezing, hoarse voice) and/or the cardiovascular system (hypotension, collapse). See chapter 1, Medical emergencies, p. 6.

Management

History

- Take a detailed history including details of the reaction, time after ingestion, treatment required, prior and subsequent exposures and co-existence of other atopic disease.

- Clarify whether there are symptoms of allergy to any other foods: 30% of children with food allergy will be allergic to more than one food. The finding that a food is being taken in the diet in significant quantities (i.e. whole egg rather than small amounts of egg contained within cakes or biscuits) without reaction effectively excludes the presence of clinical allergy to that food and SPT and RAST to that food is not indicated.

- Patients are instructed to avoid the food that caused the allergic reaction. This requires careful reading of ingredient labels. Current Australian food labelling laws require that the common food allergens are listed as an ingredient if they are used in the preparation of a food.

- In IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy, cow’s milk products should be eliminated. In infants and young children, a soy-based milk can be used if the child is not also allergic to soy. Where a child is also allergic to soy, a formula in which the milk proteins are broken down into hypoallergenic fragments (protein hydrolysate) should be used. Examples in Australia include Alfaré and Pepti-Junior. Occasionally, children may react to the hydrolysed milk proteins in these formulas and in such cases an elemental amino acid formula is indicated (e.g. Neocate or Elecare). Some clinicians advise that infants <6 months proceed directly to a protein hydrosylate formula (without trial of soy), because of the theoretical adverse effects of phytoestrogens in soy products, although this is not universal.

Allergy and anaphylaxis plans

- All patients with IgE-mediated food allergy must be provided with a written management plan in the event of an accidental exposure to the offending food allergen.

- Mild–moderate allergy:

– Avoid causative food.

– Give Allergy Action Plan (without an EpiPen) which is available from www.allergy.org.au

- Anaphylaxis:

– Avoid causative food.

– Refer for specialist allergy advice.

– In the interim period, consultation with a clinical immunologist, allergist, paediatrician or emergency physician should be sought to determine the need for an EpiPen.

– Prescription of an EpiPen must be accompanied by education on its use and provision of an Anaphylaxis Action Plan (available at www.allergy.org.au).

– Dose for EpiPen:

Child >20 kg, EpiPen 300 mcg.

Child 10–20 kg, EpiPen Jr 150 mcg.

Child <10 kg, not usually recommended (discuss with specialist).

Note: This is different to current product information dosage guidelines, where Epipen 300 mcg is recommended for children >30 kg.

Investigation

- Confirm the presence of mild–moderate IgE-mediated reaction (not anaphylaxis) to the suspected food if it is one of the common food allergens (e.g. milk, egg, peanut) with a SPT or RAST to that food. A negative SPT or RAST almost eliminates the possibility of an immediate IgE-mediated reaction to that food. A positive SPT or RAST confirms food allergy if there is a convincing history. If the history is uncertain, further evaluation by formal challenge is required. Parents should not challenge children with a suspected food at home as severe reactions and even death have occurred.

- Performing SPT or RAST to other common food allergens (egg, milk, wheat, soy, peanut, shellfish, fish) to which the child has not yet been exposed may be indicated.

Refer to paediatric allergy specialist

- Children with anaphylaxis.

- Children suspected of having multiple food allergies, including children with confirmed allergy to one food and not yet exposed to one or more of the other common food allergens.

- Children with an unclear history or those who are likely to require retesting or challenge.

- Children with multiple atopic diseases.

Non-IgE-mediated and mixed IgE/non-IgE mediated food reactions

- Non-IgE-mediated food reactions are much less common.

- Generally these are delayed reactions occurring 24–48 h after food ingestion, although some infants may have immediate non-IgE-mediated food reactions that occur within 1–2 h of food ingestion.

- Typically, gastrointestinal symptoms are prominent with vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal cramps. Occasionally there may be malabsorption, weight loss or slow weight gain. Worsening of eczema may also occur.

- In severe cases (e.g. food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome, FPIES) there may be cardiovascular collapse.

- Cow’s milk and soy proteins are the most common foods implicated.

- Diagnosis requires elimination of the suspected food followed by formal food challenge.

- Skin-prick testing is usually negative, but may be positive if there is a mixed aetiology, which includes some IgE-mediated reaction.

- Treatment is with avoidance of the offending food. Specialist consultation is recommended.

- Infants with non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy should be given an extensively hydrolysed protein formula.

- 50% of cases resolve within 1–2 years.

Food-protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES)

- A form of non-IgE mediated food allergy seen in young infants usually <6 months.

- Usually due to cow’s milk, soy or cereals (e.g. rice).

- Can be seen in exclusively breast-fed infants.

- Can be seen in older children with other foods (e.g. egg).

- Typically delayed onset (>1–2 h) of projectile vomiting (that may become bilious) and protracted diarrhoea.

- May be associated with hypotension in 15% of cases (significant pallor and lethargy) that may be misdiagnosed as sepsis.

- Stool: occult blood, polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), eosinophils, reducing substances.

- Symptoms resolve within 72 h of substance elimination.

Food-protein-induced enteropathy

- A spectrum of disorders that present with protracted diarrhoea, vomiting in 2/3 and slow weight gain.

- Cow’s milk is the most frequent cause. Others include soy, egg, wheat, rice, chicken and fish.

- It has been suggested that coeliac disease represents the most severe form.

- Endoscopy/biopsy shows patchy villous atrophy with cellular infiltrates.

- Symptoms resolve after 6–12 weeks of elimination of the responsible food allergen. Improvement in appetite, vomiting, and diarrhoea may occur within 2–4 weeks; however, weight gain may take 8–12 weeks.

Food-protein-induced colitis

- First weeks to months of life.

- Usually cow’s milk or soy, but 50% of infants with this condition are breast-fed.

- Present with isolated bloody stool (gross or occult).

- Otherwise clinically well.

- Endoscopy shows mucosal oedema, ulceration, erosions that are restricted to distal bowel.

- Symptoms resolve within 72 h of elimination of the offending food.

Eosinophilic oesophagitis

- May be a cause of gastroesophageal reflux (GOR).

- Up to 40% of GOR in infants <1 year that is unresponsive to medical therapy may be due to cow’s milk allergy.

- May present as infantile colic.

- Infants often have other allergic disease, elevated IgE, peripheral blood eosinophilia and positive SPT to foods.

- Can occur in older children and adults, where it commonly presents as dysphagia.

- Endoscopy shows eosinophilic infiltrates in the oesophagus.

- Symptoms resolve within 72 h of elimination of the offending food.

Eosinophilic enteritis

- Presents with postprandial symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

- Other presentations include slow weight gain in infants, iron deficiency anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and steatorrhoea in adults.

- Endoscopy shows eosinophilic infiltrates in the stomach and/or duodenum.

- Symptoms resolve within 72 h of elimination of the offending food.

Allergic factors in atopic dermatitis (eczema)

See also chapter 23, Dermatologic conditions, p. 277.

Atopic dermatitis has a major impact on the lives of patients and their families. Allergic and infective factors may play an important role in the exacerbation of eczema and this should always be considered in moderate or severe disease. Avoiding the relevant allergic factors can improve symptom control in the context of optimal medical management.

- Staphylococcus aureus infection can have several clinical presentations including folliculitis (often punctuate), impetigo (crusting) and discoid lesions. Treatment of acute staphylococcal infection and reduction of staphylococcal loads on the skin can provide significant improvement of eczema control. Staphylococcal infection and/or colonisation must be controlled before the benefits of other allergen-avoidance measures can be assessed.

- House dust mite sensitivity is another important exacerbating factor in atopic dermatitis. Dust mite allergen is ubiquitous in the home environment, particularly in the bedroom where a child spends up to 10 h each day. In patients with sensitivity to house dust mite allergen, instituting the appropriate avoidance measures may be beneficial (see Allergic rhinitis, p. 228).

- Immediate food hypersensitivity reactions can also act as exacerbating factors, particularly in young children with severe atopic dermatitis and generalised erythema. Patients requiring investigation for possible food triggers should be referred for specialist allergy advice.

- In a small number of severe cases, there may be delayed reactions to foods. There are no skin or blood tests that can reliably identify whether delayed reaction to a food is occurring. The implementation of a restricted diet followed by systematic reintroduction of suspected foods is used to assess this. These dietary manipulations are often complex and difficult to interpret. Specialist advice from a paediatric allergist and dietician is required. Appropriate case selection is important. Dietary restrictions should not be instituted in children with mild atopic dermatitis that can be readily controlled with the appropriate topical medication.

See also chapter 36, Respiratory conditions, p. 505.

Allergic factors may contribute to the symptoms of asthma, particularly in cases of chronic persistent asthma. Investigation for allergens to which a patient is sensitised should be pursued in any patient requiring maintenance anti-inflammatory corticosteroid therapy, particularly those with interval symptoms. The avoidance of relevant allergic factors represents a simple, inexpensive and non-pharmacological approach to anti-inflammatory therapy. However, allergen avoidance represents only one component of the overall management of asthma. Patients should understand that allergic factors are not the sole cause of asthma.

- The major allergens implicated are the indoor inhalants (house dust mite, cat and dog dander). Pollens may also contribute to seasonal exacerbations of asthma, especially if the patient also suffers from seasonal allergic rhinitis. Moulds may trigger asthma symptoms in arid climates.

- Allergic rhinitis can exacerbate asthma and untreated persistent rhinitis may be one of the reasons for a failed response to standard anti-asthma therapy. Co-existent allergic rhinitis should be considered in all patients with asthma – it is common and treatable.

- Foods generally do not induce asthma symptoms in isolation. They may cause asthma symptoms as part of an immediate allergic reaction (i.e. anaphylaxis) when cutaneous eruptions are usually also observed.

- In some patients with chronic asthma, the preservative metabisulfite can provoke an acute exacerbation. Confirmation of this requires specialist consultation.

- NSAIDs (e.g. aspirin) may exacerbate asthma symptoms in some patients with chronic asthma. Specialist consultation is required to confirm this.

Urticarial rashes

Also known as hives, urticarial rashes are raised areas of erythema and oedema, which are usually itchy and move over the body over several hours. They are classified as acute (<6 weeks’ duration) or chronic (>6 weeks’ duration).

Acute urticaria

- Often only lasts a few days.

- In the vast majority of cases, no precipitating factor is identified.

- The most important step is to take a careful history to look for possible exposure to drugs (especially antibiotics) or foods that may have induced an immediate hypersensitivity reaction. If a precipitating factor cannot be identified on history, SPT and RAST will generally not provide additional information and are not indicated.

- Some cases follow viral or streptococcal infections.

Chronic urticaria

- Can persist or occur intermittently for months or years.

- The possibility of a physical urticaria (e.g. heat, cold or cholinergic) should be considered.

- In protracted cases, it is important to consider the possibility of an underlying connective tissue or autoimmune disorder that may (rarely) present as chronic urticaria. In these cases, there are usually other suggestive features such as arthritis or vasculitis. Biopsy of lesions for histologic analysis may be helpful in identifying vasculitis.

- Chronic urticaria is rarely caused by specific allergic factors and therefore investigation with SPT and RAST is not helpful.

Angio-oedema

- Swelling of the deeper tissues that is not necessarily itchy. It often involves areas of low tension, such as the eyelids, lips and scrotum.

Treatment of both acute and chronic urticaria

- Symptomatic: treat with second-generation antihistamines. Cetirizine is particularly effective (for doses see Table 19.2).

- Manipulation of the diet is generally not helpful and is not indicated in children. A small number of subjects may respond to a preservative and colouring-free diet; however, this should only be considered if symptoms are particularly troublesome.

- In resistant cases, the combined use of an H2 antihistamine (cimetidine) with standard H1 antihistamines may be considered but success is limited.

- Rare autosomal dominant condition in which C1 esterase inhibitor levels are reduced (HAE type I) or poorly functional (HAE type II), resulting in uninhibited activation of the complement, kinin and fibrinolytic cascade.

- This results in recurrent episodes of angio-oedema involving limbs, upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. Hence patients present with:

– Angio-oedema without pruritis or urticaria.

– Abdominal pain ± nausea/vomiting (due to intestinal oedema).

– Laryngeal oedema.

- Diagnosed by the finding of low C1 esterase inhibitor level or function. C4 level is also low during episodes of angio-oedema.

Management

Refer to the Clinical Practice Guideline www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide [C1 Esterase Inhibitor Deficiency].

- Adrenaline, antihistamines and corticosteroids have no role in the management.

- Tranexamic acid may be considered in mild episodes to shorten the duration of symptoms.

- Severe angio-oedema episodes can be fatal. I.v. C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate should be administered.

- Children undergoing surgery: preoperative discussions with the anaesthetist, immunologist and intensive care unit are recommended. Consider the use of danazol for 5–10 days before surgery.

Reported allergy to antibiotics in children is common; however, many patients are incorrectly labelled as ‘antibiotic allergic’. Careful history is required to identify those patients who are likely to have experienced true antibiotic reactions. This includes details of the reaction and its timing in relation to drug dose; prior and subsequent drug exposure; concurrent illness; and other concurrent new food or drug ingestion.

Reactions may be IgE mediated or non-IgE mediated. The most common presentation is a cutaneous eruption, either urticarial or maculopapular. More severe reactions are anaphylaxis with angio-oedema and bronchospasm or laryngeal oedema, exfoliative dermatitis, Stevens– Johnson syndrome, or serum sickness with arthralgia. Multiple antibiotic allergies where a child is reported to react to a significant number of antibiotics are not uncommon.

The most common reactions are to the penicillin family. Allergy to penicillin or its derivatives is associated with a 10% risk of reaction (through cross-reactivity) to the first-and second-generation cephalosporins. This does not extend to third-generation cephalosporins, as reactions to these are usually directed to side chains.

Management

- No completely adequate in vitro or in vivo tests diagnose drug allergy.

- The detection of IgE antibodies by RAST or SPT may be helpful in the evaluation of penicillin or amoxycillin reactions.

- Skin-prick testing regimens have been established for the penicillin metabolites; however, neither positive nor negative tests accurately predict actual reaction to drug administered. Skin testing for other antibiotics is even less helpful.

- In most cases, an oral challenge initiated under observation and then continued on an outpatient basis is required to confirm or exclude allergy.

- An assessment should be made of the severity of the reaction. Each case must be judged on its merits.

- If there has been anaphylaxis with cardiovascular and/or respiratory problems, the patient should not be challenged with the drug again except in exceptional circumstances and after appropriate evaluation.

- Other contraindications to challenge include severe mucocutaneous reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome or exfoliative dermatitis and serum sickness. In these instances, an alternative class of antibiotic should be selected. In deciding whether to proceed with a challenge, a judgement should also be made regarding the importance of the antibiotic in question.

- In the vast majority of cases with the question of multiple antibiotic allergies, a challenge is carried out with a single antibiotic selected as being appropriate for future use and the challenge is completed without reaction.

Latex products contain two types of compounds that can cause reactions: chemical additives that cause dermatitis and natural proteins that induce immediate allergic reactions. Most reactions to latex in the hospital setting involve disposable gloves; however, other items including catheters, dressings and bandages, i.v. tubing, stethoscopes and airways may contain latex. Common latex products used in the community include balloons, baby-bottle teats and dummies, elastic bands and condoms. Reactions to latex products may be irritant or immune mediated.

Irritant dermatitis

Irritant dermatitis is the most common problem encountered with the use of latex gloves. This is a non-allergic skin rash characterised by erythema, dryness, scaling and cracking. It is caused by sweating and irritation from the glove or its powder or by irritation as a result of frequent washing with soap and detergents.

Immediate allergy to latex

Type I hypersensitivity reactions to latex are the most serious as they are potentially life threatening. They are caused by IgE antibodies to latex proteins. Reactions may occur after contact with latex (e.g. gloves and catheters) or the inhalation of airborne powder particles containing allergenic latex proteins.

- Sensitisation may occur following direct exposure of mucosal surfaces to latex (e.g. catheterisation).

- The severity of the reaction may vary widely, ranging from isolated allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, urticaria or asthma, to anaphylaxis and death.

- Certain populations are at high risk for developing latex allergy: children with spina bifida or other urogenital anomalies and individuals undergoing multiple surgical procedures, particularly if they are atopic.

- SPTs and/or RASTs are useful in confirming suspected sensitisation. SPTs are more reliable than RAST; however, well-standardised SPT extracts are not widely available.

- There is no cure for latex allergy. The best approach is to avoid exposure.

- There may be cross-reactivity between latex and certain foods, in particular avocado, kiwi fruit and banana. Latex-allergic individuals who experience discomfort in the mouth or throat while eating these foods should avoid them.

Contact dermatitis

This is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity to chemical additives used in processing latex. Reactions are limited to the site of contact. Use of rubber gloves results in eczematous lesions on the dorsum of the hands. The skin may become dry, crusted and thickened. Oral reactions caused by dental appliances or balloons, and genital reactions caused by condoms have been described. The use of cotton lining gloves inside latex gloves or a change to gloves that do not contain the chemicals contained in latex gloves usually reduces the problem. Patients with irritant and contact dermatitis are at an increased risk of developing immediate hypersensitivity to latex and exposure to latex should be minimised.

Management

- Patients at high risk for latex sensitivity should be referred to a paediatric allergist/immunologist for further evaluation.

- Patients who have a confirmed latex allergy (either immediate or delayed) should undertake strict latex avoidance including having latex-free precautions during surgery.

There are relatively few indications for specific injection immunotherapy in paediatric practice.

Immunotherapy has traditionally been administered by subcutaneous injections. In general, injections are given weekly, in increasing dosage until the maintenance dose has been achieved. This is done under close supervision by practitioners trained in the early identification and management of allergic reactions and anaphylaxis. Once maintenance doses have been achieved, injections are continued monthly, often by a GP, for a period of 3–5 years. Immunotherapy is not undertaken lightly. It requires a long-term commitment to therapy and may be associated with severe reactions (anaphylaxis). Consideration of pain management and psychological support is essential, especially in young children or those who are frightened of needles.

Bee venom anaphylaxis

- Immunotherapy with purif ed bee venom is indicated for life-threatening anaphylactic reactions to bee stings in children. Referral should be made to a paediatric allergist/immunologist for allergy testing and further management.

- Severe local reactions to bee stings are not an indication for immunotherapy and do not require further investigation with skin-prick testing.

- SPTs and RASTs to bee venom are not predictive of systemic reactions and in general are not indicated except to confirm the presence of bee venom sensitisation before initiation of bee venom immunotherapy in those with previous bee sting anaphylaxis.

Allergic rhinitis

- Immunotherapy may be an option in severe seasonal allergic rhinitis if the symptoms are not controlled with allergen avoidance and maximal medical therapy (topical anti-inflammatories and antihistamines), particularly if a limited number of allergens can be identif ed.

- Extreme caution is required in administering immunotherapy to unstable asthmatic patients, as deaths have resulted.

Note: Sublingual administration of allergen for immunotherapy (to environmental allergen) is used widely in Europe and is being used increasingly in Australia. Evidence of efficacy in children is currently lacking. Further studies are required before routine use can be recommended, but it may offer an alternative approach in the future.

Guidelines for the investigation and treatment of immunodeficiency

When to suspect immunodeficiency

Immunocompetent children average 5–10 viral upper respiratory tract infections per year in the first few years of life (even more if the child attends childcare or has older siblings). Recurrent viral infections in a well, thriving child do not suggest immunodeficiency. Immune deficiency should be suspected when there is a history of severe, recurrent or unusual infections.

- Recurrent or chronic bacterial infections (e.g. persistently discharging ears or purulent respiratory secretions) or more than one severe pyogenic infection may indicate antibody deficiency.

- Severe or disseminated viral infections, persistent mucocutaneous candidiasis, chronic infectious diarrhoea and/or failure to thrive in infants suggest a severe T-cell deficiency. These children should be investigated for severe combined immune deficiency (SCID). SCID should be managed as a paediatric emergency.

- The presence of autoimmune cytopenias, together with recurrent sinopulmonary infections, raises the possibility of less severe forms of combined immune deficiency.

- Recurrent pyogenic infections affecting lymph nodes, skin, lung and bones suggest a neutrophil defect.

- Recurrent or severe meningococcal disease suggests a late component complement deficiency.

- Early component complement deficiencies may present with clinical features that are similar to antibody defects or with autoimmune disease.

Which tests to order

Basic immunodeficiency screen

- An FBE with differential and immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgA and IgM) will identify the vast majority of treatable primary immunodeficiencies (e.g. agammaglobulinaemia, common variable immune deficiency, selective IgA deficiency and SCID). IgG subclass levels should not be done as part of a basic immunological screen, as isolated IgG subclass deficiency is of uncertain clinical significance.

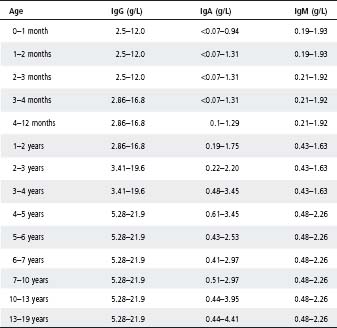

- Note that immunoglobulin levels vary with age and are lower in infancy and early childhood. It is therefore important that the relevant age-related reference ranges are used (see Table 19.3).

- If these tests are normal and the clinical suspicion of immune deficiency persists, referral to a clinical immunologist for further evaluation is indicated.

Specific antibody responses

- Only consider when there is evidence of persistent or recurrent suppurative upper and/or lower respiratory tract infection and hypogammaglobulinaemia has been excluded.

- Ask the question: ‘If an antibody defect is found, does this clinical condition warrant regular gammaglobulin therapy?’

- The most important question is whether appropriate antibodies can be made to specific protein and polysaccharide antigens. Abnormal IgG subclass levels may be a clue to an evolving antibody deficiency. However, isolated abnormalities of IgG subclasses with normal specific antibody responses rarely result in clinical problems. In general, regular gammaglobulin therapy is only indicated for severe recurrent infections when a specific antibody defect has been identif ed.

T-lymphocyte numbers and function

- Consider a chest radiograph to look for absent thymic shadow when a T-lymphocyte defect is suspected.

- Specialised T-lymphocyte function tests are used to help in the diagnosis of SCID and Di George syndrome (absent thymus, hypocalcaemia and cardiovascular anomalies). Referral to an immunologist is recommended if these conditions are suspected.

Neutrophil function tests

- Specific defects of neutrophil function (e.g. chronic granulomatous disease and leucocyte adhesion deficiency 1) are very rare. They are almost always associated with gingivitis and careful examination of the mouth is important when considering abnormalities of neutrophil function.

- Markedly elevated circulating neutrophil counts and delayed separation of the umbilical cord (>4 weeks) suggest the possibility of a leucocyte adhesion deficiency.

- Suspected cases of defective neutrophil function should be referred to an immunologist for further evaluation.

Table 19.3 Immunoglobulin normal ranges (5th to 95th percentile)

Source: Davis et al. IFCC-standardised pediatric reference intervals for 10 serum proteins using the Beckman Array 360 system. Clin Biochem, Oct 1996; 29(5): 489–92.

Complement studies

- Deficiencies of complement are rare.

- The best screening test for congenital deficiency is a CH50, which measures the function of the classical complement pathway.

HIV tests

HIV testing should be considered in the setting of recurrent, severe or unusual infections, particularly if there is hypergammaglobulinaemia. Testing requires informed consent and appropriate counselling. This specialised immune function testing is best undertaken in consultation with a clinical immunologist.

Immunodeficiency treatment

Immunisation

See also chapter 9, Immunisation.

- As a general rule, all live viral vaccines should be avoided in immunodeficiency unless advised by a specialist.

- Patients with a T-cell defect and their immediate family should receive the killed injectable polio (Salk) vaccine, not live oral polio vaccine. This is now the standard form of polio vaccine in Australia.

- In certain circumstances, measles immunisation may be given to patients with a T-cell defect (e.g. Di George syndrome or paediatric HIV infection) as the risks of wild-type measles infection are considerable, but adverse reactions to the vaccine are largely theoretical.

- In cases of antibody deficiency, T-cell deficiency and combined immunodeficiency, immunisation with killed vaccines will not promote a significant antibody response.

- If the patient is on immunoglobulin replacement therapy, passively acquired antibody will prevent viral infections such as measles and chickenpox. See also chapter 9, Immunisation.

- Patients of any age with asplenia should be immunised with Hib, pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines.

Immunoglobulin therapy

- Immunoglobulin therapy (400–600 mg/kg i.v. monthly) is given when a significant deficiency of antibody production is demonstrated in a patient with clinically significant infections (usually sinopulmonary).

- In hypogammaglobulinaemia, immunoglobulin therapy is generally lifelong.

- In patients with combined immunodeficiency, immunoglobulin treatment may be discontinued once normal B-cell function can be demonstrated following bone marrow transplantation.

- In patients with IgG subclass deficiency, immunoglobulin therapy is indicated only if a significant functional antibody deficit is demonstrated and the patient has significant symptoms. In this instance, a trial of immunoglobulin therapy may be used for a restricted period of time to determine if there is clinical benef t. This should only be instituted in conjunction with a clinical immunologist.

- The f nding of a low immunoglobulin subclass level alone is not a sufficient indication for immunoglobulin therapy. Immunoglobulin therapy is not indicated for isolated IgA deficiency. These patients should be referred to a specialist for further evaluation and/or follow up.

- Three forms of immunoglobulin are currently available for i.v. administration in Australia: Intragam P (produced from Australian plasma), Octagam and Sandoglobulin (imported products).

– IgG concentrations and rates of administration differ in the different products and need to be taken into account when these products are administered.

- The subcutaneous route for administration of immunoglobulin for replacement purposes is being used widely overseas and increasingly in Australia. Potential benef ts include ease of administration in patients where venous access is limited and capacity for home immunoglobulin delivery. A more concentrated immunoglobulin product is used for these purposes.

Antibiotics

- As immunoglobulin therapy does not provide significant levels of IgA antibody (the mucosal surface antibody), aggressive treatment of respiratory infections in patients with antibody deficiency is important in order to prevent bronchiectasis and permanent damage to the lungs.

- In severe cases, prophylactic rotating antibiotics are used to prevent recurrent severe sinopulmonary infections.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole 2.5/12.5 mg/kg (max. 80/400) p.o. b.d. 3 days per week is indicated in patients with T-cell or combined immune deficiency to prevent infection with pneumocystis.

Use of blood products

- If it is suspected or known that the patient has a significant T-cell deficiency, blood products that contain cells (e.g. whole blood, packed red cells or platelets) should be irradiated to prevent graft versus host disease.

- In infants with SCID or any significant T-cell deficiency, attempts should be made to provide cytomegalovirus (CMV) antibody-negative blood, as CMV infection can be a significant problem in such patients. If this is not possible, the blood product should be filtered to remove contaminating white blood cells as it is delivered to the patient. If possible, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) antibody-negative blood should also be given, as EBV can induce lymphoproliferative states in severely immunodeficient subjects.

- Patients with IgA deficiency may develop IgE antibodies to IgA and have an anaphylactic reaction to blood products containing IgA (i.v. immunoglobulin, packed red cells, platelets). Immunoglobulin preparations that are depleted of IgA should be used and packed cells or platelets should be washed four times in physiological saline before infusion.

Bone marrow transplantation

- Bone marrow transplantation is the definitive treatment for SCID. It may also be useful for the treatment of other immune deficiencies (e.g. chronic granulomatous disease, hyper IgM syndrome).

- The cure rate can be of the order of 80% if the transplant is from a matched sibling or a parent.

- Survival is less, in the order of 50%, if the transplant is only partially matched and from an unrelated donor.

USEFUL RESOURCES

- www.allergy.org.au – The Australian Society of Clinical Allergy and Immunology. Contains excellent information for patients and health care professionals. Includes anaphylaxis action plans.

- www.primaryimmune.org – Immune Deficiency Foundation. Patient organisation website containing excellent handouts for primary immune deficiencies.

- www.esid.org – Eurpean Society for Immunodeficiencies. Contains a useful clinical section which details diagnostic criteria of various primary immunodeficiencies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree