Developmental surveillance

Developmental surveillance is a flexible continuous process of skilled observation as part of providing routine health care. It should occur opportunistically whenever a child comes into contact with a health professional.

If a parent is concerned about a child’s development it is highly likely that evaluation will confirm developmental delay; however, a lack of concern from parents is no guarantee that the child’s development is normal. The PEDS (Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status) consists of 10 questions based on research of parents’ concerns. It aims to systematically elicit parents’ concerns and guide referral decisions. It is validated from birth to 8 years. It is simple to administer and can be used in primary care settings.

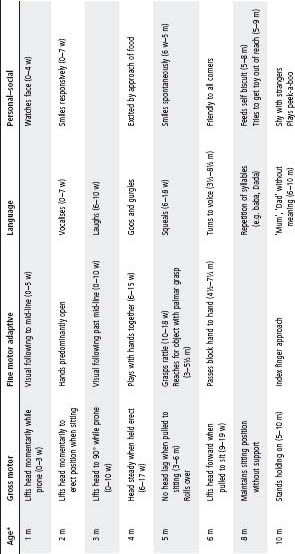

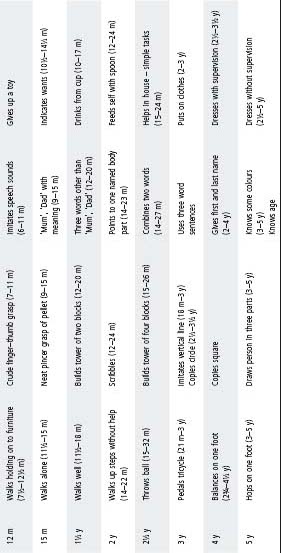

Informal clinical judgement is unreliable as a method for detecting developmental problems. Milestone checklists (see Table 14.1) serve as an aid to memory by recording what is expected of the average child at each age in several domains of developmental function. Because they record average expectations for each age, it is often difficult to distinguish the child with true developmental delay from the normal child with below-average milestone attainment.

Formal screening tests such as the Denver II and the Australian Developmental Screening Test allow the objective discrimination of the child who probably has a developmental delay from the child who probably does not. Results of screening tests are not definitive; a fail on such a test requires referral of the child for formal developmental assessment.

Table 14.1 Developmental milestones

w, weeks; m, months; y, years.

* Age indicates when at least 90% of a normal group of children will achieve the test. Figures in parentheses represent the range from 25th to 90th centiles for achievement.

Formal assessment involves a synthesis of the findings from history, physical and neurological examination, and developmental testing using standardised assessment tools such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and the Griffith’s Developmental Scales. The type of testing undertaken depends on the presence or absence of several risk factors for developmental delay (see Table 14.2).

Children with developmental delay or disability, or both, have the same basic needs as all children. They have the potential for further development and the principles of normal development apply.

Specific disabilities in one area may cause secondary disabilities in other areas (e.g. children who have motor disabilities with reduced opportunity for exploration may suffer delayed development of their comprehension abilities).

Transient developmental delay may be associated with:

- Prematurity.

- Physical illness.

- Prolonged hospitalisation.

- Family stress.

- Lack of opportunities to learn.

Causes of persistent developmental delay (developmental disability) include

- Language disorders.

- Intellectual disability.

- Cerebral palsy.

- Autism.

- Hearing impairment.

- Visual impairment.

- Degenerative disorders.

- Neuromuscular disorders.

Once suspicion regarding a child’s development has been raised, a complete paediatric consultation is required. This should include full details of the family, obstetric, neonatal and developmental histories. Liaison with the GP and a maternal and child health nurse to obtain background information is often helpful. A history of loss of previously attained developmental skills is suggestive of regression rather than delay, and requires more comprehensive investigation to exclude neurodegenerative conditions. Observation of how the child looks, listens, moves, explores, plays, communicates and socialises is essential before the formal examination. Understandably, parents will be anxious and a sensitive approach is essential at all times.

Developmental assessment provides the family with an understanding of the child’s development and outlines developmental goals and strategies to reduce any handicapping effects of the disability. Assessment and management may include input from physiotherapists, speech pathologists, teachers, occupational therapists, psychologists and social workers.

Principles of assessment

These include:

- Utilisation of play as a fundamental assessment tool.

- Promotion of optimal performance of the child.

- Gearing the assessment towards remediation rather than merely producing a profile.

- Involvement of the parents in the assessment process.

- Close linking of the assessment with services offering help and support.

Table 14.2 Children at risk of developmental problems

| Risk group | Risk factors | Action |

| High | Developmental regression | Bypass developmental screening |

| Abnormal neurology | Refer for comprehensive developmental assessment | |

| Dysmorphism | ||

| Chromosomal abnormality | ||

| Hearing or vision problems | ||

| Moderate | Parents suspect developmental delay | Administer a formal screening test |

| History of severe pre- or perinatal insult | Pass – reassure that development is within normal range and continue surveillance through a local doctor/ maternal and child health nurse | |

| Very low birthweight (<1500 g) | Questionable – repeat the test 4 weeks later | |

| Family history of developmental delay | Fail – refer for comprehensive paediatric consultation and developmental assessment | |

| Severe socio-economic or family adversity | ||

| Low | No parental or professional concerns | Developmental surveillance by a local doctor/maternal and child health nurse is recommended |

| No other risk factors | Should there be later parental or professional concerns, a formal screening test is recommended | |

| If there are no further concerns, continue surveillance monitoring |

Early intervention

Early intervention includes prevention and early detection of disabilities, as well as health, educational and community services that assist the child, family and community in adapting to the child’s developmental needs and disability. Services are based on the principles of inclusion and integration into regular settings.

The aims of early intervention are to minimise the handicapping effects of the child’s disability on their development and education, and to support the family in understanding and providing for their child’s individual needs. Services include individual teaching and therapy (speech and occupational therapy), family support and counselling, providing resources and support to childcare, preschools and respite care. Services are usually regionally based and are provided by government and non-government agencies. Unfortunately, waiting lists for these Early Childhood Intervention Services (ECIS) can be many months and it is important to provide any other services locally available while awaiting placement. Recently the Australian government has made available five Medicare-funded allied health consultations per person, per year. These are only available by GP referral, and can be used, for example, to obtain private physiotherapy or speech therapy.

Education

There is a range of special educational strategies to optimise learning and development, dependent on the child’s abilities and disabilities, with increasing opportunities for integration as resources are moved from special to local schools. A range of special schools is also available. Paediatricians liaise closely with schools to assist with meeting the child’s educational needs. Dialogue ensures appropriate support for the child’s physical and intellectual function, maximising the child’s learning potential and opportunities. This may include applying for government funding for aides, management of physical disability, seizure management and behavioural support.

Family supports

Parents need to be aware of the services that are available to them to assist in the care of their child with a disability. Supports include social security benefits, home help and respite care through foster agencies and community residential units. Consumer organisations can provide parent support, information and advocacy.

The definition of intellectual disability comprises three elements:

1 a significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning (i.e. 2 standard deviations below the mean of the intelligence quotient) that exists concurrently with

2 deficits in adaptive behaviour, and

3 manifests itself during the developmental period.

This definition is used by service providers, as well as academics and legislators. The term developmental disabilities is used increasingly to reflect the complexity of development.

Up to 2.5% of children have an intellectual disability: approximately 2% mild and 0.5% moderate, severe or profound.

Causes of intellectual disability

Prenatal

- Chromosomal; e.g. trisomy 21, fragile X syndrome and velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11-deletion syndrome).

- Genetic; e.g. tuberous sclerosis and metabolic disorders.

- Major structural anomalies of the brain.

- Syndromes; e.g. Williams, Prader–Willi, Rett.

- Infections; e.g. cytomegalovirus.

- Drugs; e.g. alcohol.

In addition, children of low birthweight are at risk for intellectual disability: the lower the birthweight, the greater the risk.

Perinatal

- Infections.

- Trauma.

- Metabolic abnormalities.

Postnatal

- Head injury.

- Meningitis or encephalitis.

- Poisons.

Presentation

- At birth with a known syndrome or malformation.

- At follow-up in high-risk infants.

- Language delay.

- Global developmental delay.

- Learning difficulties.

- Behaviour problems.

- With associated medical complications (e.g. epilepsy).

A biological cause for moderate, severe and profound intellectual disability can be identified more readily than in those with a mild intellectual disability. In disability requiring extensive support, a cause may be identified in up to 2/3 of cases. In people with mild intellectual disability, the cause is identifiable in <20% of individuals. Where a cause is identified, the majority are caused by problems during the prenatal period with 10% due to perinatal and 5% due to postnatal insults. The three most common identifiable causes of intellectual disability are trisomy 21, fragile X syndrome and velocardiofacial syndrome.

Investigations

It is important to establish aetiology where possible in order to understand prognosis, provide genetic counselling and to ensure that associated problems are detected.

The following investigations should be considered:

- Chromosomes, especially for fragile X, William and Prader–Willi syndromes using DNA probes and FISH for 22q11-deletion.

- MRI of the brain.

- Creatinine phosphokinase in boys (for neuromuscular disorders).

- Plasma amino acids.

- Urinary organic and amino acids.

- Thyroid function tests.

- Mucopolysaccharide screen.

- Investigation for congenital infection: ophthalmological and audiological examination, maternal/infant serology and viral culture (cytomegalovirus).

Despite thorough investigation, the cause is often not identified.

Management

- Support and information for parents.

- Referral to and liaison with other practitioners, early intervention, family support and educational services.

- Child advocacy.

- Regular assessment of vision and hearing.

- Investigation for associated anomalies (e.g. cardiac and thyroid status with trisomy 21).

- Treatment of associated disorders (e.g. epilepsy).

- Monitoring of development.

Cerebral palsy is a persistent, but not unchanging, disorder of movement and posture due to a defect or lesion of the developing brain.

Aetiology

Cerebral palsy is not a single entity but a term used for a diverse group of disorders, which may relate to events in the prenatal, perinatal or postnatal periods. In many children the cause is unknown. Perinatal asphyxia accounts for <10% of cases and postnatal illnesses or injuries for a further 10%. There is a significant association with low birthweight and prematurity, particularly for infants weighing <1500 g at birth. The overall prevalence is approximately 2.0/1000 live births.

Classification

This is according to:

- The type of motor disorder, e.g. spasticity, dyskinesia (includes dystonia and athetosis) and ataxia.

- The distribution, e.g. hemiplegia, diplegia and quadriplegia.

- The severity of the motor disorder, using the Gross Motor Function Classification System.

Spectrum of cerebral palsy and associations

- Children with cerebral palsy are an extremely heterogeneous group and the degree of handicap experienced varies enormously. Approximately 30% are hemiplegic, 25% diplegic and 45% have quadriparesis.

- The most common type of motor disorder is spasticity. This can lead to significant complications if not well managed, the most severe being contractures and hip subluxation.

- Some children have an isolated motor disorder. However, an estimated 70% of children with cerebral palsy have associated disorders including visual problems, hearing impairment, communication disorders, epilepsy, intellectual disability, specific learning disability or perceptual problems.

- Other complications include incontinence and constipation, feeding and nutritional problems, poor dental health and poor salivary control. These are usually multifactorial.

Management

General management

- An accurate diagnosis with genetic counselling.

- Management of the associated disorders, health problems and consequences of the motor impairment.

- An assessment of the child’s capabilities and referral to the appropriate services for the child and family. Liaising with the kindergarten, school and GP is important.

- Attention to usual childhood issues of growth, immunisation and dental health.

Management of commonly associated disabilities and health problems

- All children require hearing and visual assessment.

- Careful assessment and management of epilepsy is required.

- Children may benefit from formal cognitive assessment.

- Nutritional problems: obesity can occur because of an imbalance between intake and physical activity. Conversely, children may be underweight, particularly in the presence of oromotor problems that may result in major feeding difficulties. Dietary advice is important. The presence of severe slow weight gain, major feeding problems or aspiration, or all of these, may be indications for non-oral feeding by a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube.

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux occurs commonly in cerebral palsy.

- Continence issues.

- Undescended testes occur more frequently in boys with cerebral palsy than in the general population.

- Constipation requires dietary and laxative advice.

- Aspiration and lung disease may be associated with impaired oromotor control. Chronic cough with wheeze or repeated lower respiratory infections may indicate the presence of chronic lung disease. Videofluoroscopy is a useful test for the detection of aspiration.

- Osteoporosis with pathological fractures may occur in cerebral palsy. This is often compounded by vitamin D deficiency and serum levels ought to be monitored, especially in children with limited sun exposure.

- Psychological and social difficulties require careful attention.

Management of the consequences of the motor disorder

- Saliva control can be improved with techniques employed by speech therapists, or by the use of anticholinergic medication or surgery in a small group of children.

- Spasticity management is aimed at improving function, comfort and care and requires a team approach. Options include:

– Oral medications, e.g. diazepam, baclofen and dantrolene.

– Inhibitory casts to increase joint range and facilitate improved quality of movement.

– Botulinum toxin A for localised spasticity.

– Intrathecal baclofen is suitable for a small number of children with severe spasticity.

– Selective dorsal rhizotomy – a treatment option for a selected group of children with severe spastic diplegia.

Orthopaedic problems

The orthopaedic management of cerebral palsy requires a team approach. Dynamic spasticity, which interferes with function in young children, is best managed by conservative methods (e.g. orthotics, inhibitory casts or the use of botulinum toxin A). Surgery is mainly undertaken on the lower limb, but is occasionally helpful in the upper limb. Some children also require surgery for scoliosis. Physiotherapy is an essential part of postoperative management. The advice of occupational therapists on strategies and equipment to overcome barriers into and within the home of an immobilised child postoperatively is often of great assistance to families. Gait laboratories are useful in planning the surgical programme for ambulant children. The critical parts of the body to observe are:

- The hips: non-walkers and those only partially ambulant are prone to hip subluxation and eventual dislocation. Early detection is important and hip radiographs should be performed at yearly intervals or more frequently if there is concern. Dislocation, which may cause pain and difficulty with perineal hygiene, is extremely difficult to treat once it occurs and prevention by early adductor releases is a better strategy. Hip problems may also occur in mobile children (e.g. those with severe hemiplegia). However, this is rare.

- The knees: hamstring surgery may be necessary to improve gait pattern, or the ability to stand for transfers.

- The ankles: there may be a range of problems around the foot and ankle. Conservative treatments are used in young children but surgical correction is frequently required later.

- Multilevel surgery: sometimes children require surgery at several different levels, e.g. hip, knee and ankle.

Referrals

Referral to and ongoing liaison with allied health professionals is essential to enable children to achieve their optimal physical potential and independence.

- Physiotherapists give practical advice to parents and carers on positioning, handling and play to minimise the effects of abnormal muscle tone and encourage the development of movement skills. They also give advice regarding mobility aids, the use of orthoses or special seating. They may provide individual or group treatments or refer to appropriate community services.

- Occupational therapists provide parents with advice on developing their child’s upper limb and self-care skills, often suggesting suitable toys to encourage skill development. OTs design and make hand splints, and provide advice on equipment and house adaptations for home care.

- Speech pathologists provide guidance for those with severe eating and drinking difficulties, and communication and augmentative communication systems for children with limited verbal skills.

- Orthotists/prosthetists provide design/fabricate/fit and maintain various orthoses (braces) and prostheses (artificial limbs). Orthoses are used to improve function, support, align, prevent or correct musculoskeletal deformities in different parts of the child’s body, more commonly the lower limbs. As part of the allied health team, orthotists work closely with the referring specialist and other allied health team members to optimise the child’s potential.

- Other professionals who may be helpful include medical social workers, nurses, psychologists and special education teachers.

- GPs play an important role in supporting these children and their families in the community.

Irritability in children with profound disability

Refer to Pain in children and adolescents with disabilities, p. 70.

Irritability in children can present the clinician with diagnostic uncertainty, amplified in those patients with difficulties in communication or complex medical illness. In children with severe cerebral palsy the following differentials should be considered:

- Muscle spasm.

- Seizure.

- Pain:

– Consider all the usual sites of infection (e.g. otitis media, urinary tract, throat, sinusitis, respiratory tract and skin).

– Gastro-oesophageal reflux.

– Dental abscess/caries.

– Corneal abrasion/foreign body in the eye.

– Pancreatitis.

– Renal colic.

– Surgical – appendicitis, intussusception, torted testes.

– Severe constipation.

– Subluxing or dislocated hips.

– Fractures – accidental or inflicted.

– Side effects of medication e.g. anticonvulsants.

– Gynaecological.

– Sleep deprivation (associated with pain and spasm).

– Increased intracranial pressure (many children have VP shunts).

Spina bifida (myelomeningocele)

Spina bifida is the most common severe congenital malformation of the nervous system. The degree of impairment from the spinal cord pathology varies. Most children have some element of lower limb dysfunction, sensory loss and a neurogenic bladder and bowel; 80% have progressive hydrocephalus requiring surgery. Many children have specific learning problems.

Prevention

Periconceptional folic acid supplementation (in the month before and in the first 3 months of pregnancy) has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrence in any at-risk family (by ∼75%), as well as reduce occurrence in any family. Recommended doses are:

- Low-risk women (no family history of neural tube defects): 0.5 mg daily.

- Women with a previous child with a neural tube defect (or personal, partner or close family history): 4 mg daily (5 mg if 4 mg not available).

- Women with epilepsy on anticonvulsants should also be advised to take the larger dose.

Note: Multivitamin supplements are not recommended because of the potential risks of vitamin overdose to the developing fetus.

Fortification of staple foods with folate has been recommended in many countries and is currently being considered in Australia. Fewer children are now being born with neural tube defects, mainly due to antenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy. The effect of folate supplementation on incidence is not yet clear.

Management

Management requires collaboration between health, education and welfare professionals and the child and family. Most children attend regular schools. Families require a great deal of support.

An interdisciplinary team of paediatricians, surgeons, neuropsychologists, physiotherapists, orthotists, occupational therapists, social workers and stomal therapists is required to develop an appropriate developmental and rehabilitation programme, in collaboration with the family, GPs and community agencies (including local primary care service providers).

Initial management

- Neurosurgical and paediatric assessment of the newborn infant is undertaken to determine if early surgery to close the spinal defect should be recommended. Clinical and ultrasound observation to detect and monitor the presence of hydrocephalus is important. Insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt may be necessary.

- Orthopaedic and urological consultations and investigations are undertaken in the neonatal period to provide baseline information for subsequent management. A small number of infants require early management of talipes or a high-pressure neurogenic bladder.

- The families must be fully informed about the diagnosis, natural history and prognosis, and be reassured that assistance is available.

Specific aspects of management

Medical and therapy staff should monitor children regularly.

- Mobility:

– Independent mobility is the primary goal of the orthopaedic surgeon, physiotherapist and orthotist.

- Urinary tract:

– The primary goal is the maintenance of satisfactory renal function and the establishment of urinary continence (dryness) at a developmentally appropriate age.

– Clean intermittent catheterisation is now the preferred method of treatment, starting in the neonatal period. Additional support may be necessary in the form of medication (e.g. oxybutynin 8–12 hourly), protective clothing and condom drainage.

– Bladder augmentation may be required, and if it has been performed lifelong surveillance by a urologist is important because of the increased risk of malignant change. In the past artificial sphincters were used in some patients and long-term urological surveillance is also required for them. The Mitrofanoff procedure (fashioning a conduit from the bladder to the abdominal wall by using the appendix) is being used more frequently to facilitate independence in catheterisation.

– Urinary tract infection is common.

- Neurological functioning:

– Children with shunts should have neurosurgical assessment regularly (in infancy every 6–9 months; in childhood and adolescence at least every 1–2 years). See also chapter 33, Neurologic conditions, p. 470.

– Tethering of the spinal cord to surrounding structures occurs in most children. In a small number, traction on the cord causes deterioration in neurological functioning. Surgical de-tethering may be required.

– Children often have specific cognitive difficulties and a neuropsychological assessment is usually carried out before school entry and repeated before transition to secondary school.

- Miscellaneous medical problems:

– Constipation is common, and dietary advice, laxatives and enemas may be required. For children with severe continence problems anal plugs can be used following careful assessment by the stomal therapist. The Malone procedure is the fashioning of a nonrefluxing appendicocaecostomy so that an antegrade continence enema can be performed to prevent soiling.

– Scoliosis is a common management problem.

– Pressure sores occur in all children with spina bifida at some time, most commonly on the feet or the buttocks.

– Epilepsy occurs in 15% of cases.

– Latex allergy is much more common in children with spina bifida and has serious implications. Testing is offered to all children.

– Weight issues can be a problem.

- Adolescent issues:

– Puberty may be delayed or precocious.

– Specific adolescent issues including sexuality, relationship difficulties and contraception should be addressed.

– Mental health should be monitored.

– Vocational support is important.

– Transition and transfer to adult services is a major challenge and needs careful planning and support for the young person.

Autism is now seen as part of a spectrum of disorders, also known as pervasive developmental disorders. They include autistic disorder, Asperger’s syndrome and atypical autism. Diagnosis requires the presence of three core features by 3 years of age:

- Qualitative impairment of social interaction.

- Qualitative impairment in communication.

- Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of activities, behaviour and interests.

Prevalence estimates vary with definitions used but autism spectrum disorder is now thought to affect nearly 1% of the population with a sex ratio of 3 males : 1 female.

Aetiology

The aetiology of autism is unknown. Factors involved may include:

- Genetic: recurrence rate in families of 2–6%.

- Syndromal: there is an association with tuberous sclerosis, fragile X syndrome and con-genital rubella. Careful medical assessment to exclude these conditions is important.

- Structural: subtle brain abnormalities are described in some children.

Associated disorders

- Intellectual disability (75%).

- Epilepsy (20%).

- Other: ADHD, anxiety disorders and depression, Tourette syndrome.

Clinical features

Parents will often identify that something is different about their child before the second birthday. Early features include lack of:

- Pretend play.

- Pointing out objects to another person.

- Social interest.

- Joint attention.

- Social play.

Language development is delayed, with an unusual use of language. Regression of language may be seen.

Diagnosis

There is no single test for autism spectrum disorders. Diagnosis is best made by a multidisciplinary team of a paediatrician/child psychiatrist, speech pathologist and psychologist.

Management

Management is multidisciplinary. It includes:

- Parent support and education.

- Appropriate screening of vision/hearing, investigation for associated disorders/syndromes if suspected.

- Early intervention programmes, including a well-structured and predictable environment with:

– Behavioural modification.

– Speech therapy.

– Special education.

– Sensorimotor programmes.

- A combination of educational, developmental and behavioural treatments has been shown to improve a child’s rate of progress.

- Drug therapy is sometimes used to treat co-morbid psychopathology (e.g. attentional and behavioural problems, anxiety, self injury). It does not affect the core autistic symptoms.

- Advice regarding educational options.

- Support groups.

- Access to respite care.

Families of children with autism spectrum disorder will often seek alternative health care, sometimes at considerable cost. It is important for parents to be aware and informed of what is available and the evidence supporting/refuting such strategies, such that an educated choice can be made.

Asperger’s syndrome is used to describe individuals with:

- Normal intelligence (although it may range from borderline to superior).

- No obvious delay in language development.

- Impaired social and communication skills with an egocentric approach to others.

- Social immaturity.

- A narrow range of obsessional interests (such as knowledge of sporting statistics, astronomy, public transport systems).

- Lack of common sense.

Common co-morbidities

Anxiety disorders

- Obsessive compulsive disorder occurs in about 25% of people with Asperger’s syndrome.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder.

- School refusal.

- Selective mutism.

- Social anxiety disorder.

Depression

Up to 1/3 of children and adults with Asperger’s syndrome are clinically depressed.

Management

Specific educational, behavioural and supportive psychological and psychotherapeutic treatments are used.

Teaching social skills and friendship skills, emotion education and management, can help young people with Asperger’s syndrome deal with their difficulties. Clinicians monitor for the emergence of co-morbidities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree