Chronic constipation

Definition

At least two of the following problems within the previous 8 weeks:

- <3 bowel motions/week.

- >1 episode of faecal incontinence per week.

- Large stools in the rectum or palpable on abdominal examination.

- Passing of stools so large that they obstruct the toilet.

- Retentive posturing and withholding behaviour.

- Painful defecation.

Aetiology

In most children, chronic constipation (CC) is due to functional faecal retention (withholding of stool). Painful or fear of painful defecation are the most common triggers, leading to apprehension about defecation and a cycle of withholding and passage of hard retained stool.

Organic causes of CC are rare. They include:

- Cow’s milk protein intolerance, which may manifest as constipation in the first 3 years of life.

- Hirschsprung’s disease usually causes failure to pass meconium in the first 48 h of life, and virtually never causes faecal soiling.

- Slow colonic transit and motility (including neuronal intestinal dyplasia).

- Coeliac disease.

- Hypothyroidism.

- Hypercalcemia.

- Drugs (codeine, antacids).

- Spinal cord lesions.

- Anorectal malformations.

Lack of dietary fibre and poor fluid intake rarely contribute to childhood CC. Inappropriate emphasis on diet and fluid serve to lay blame on the child or parents, while defl ecting attention from treatments that do work.

Infants

Constipation of early infancy is not well understood. Dyschezia (a healthy infant, straining and crying before passing soft stool) is normal but can be mistaken for constipation. Common organic causes include anal fissures, weaning, and cow’s milk protein intolerance. Treatment with laxatives and stool softeners should be undertaken with great caution.

Defined as the passage of stool in an inappropriate place. The term faecal incontinence (FI) supersedes the terms encopresis and faecal soiling.

Aetiology

Most FI is functional and is associated with constipation (see above). Other causes include functional non-retentive FI (i.e not constipated), and organic causes from neurological damage or anal sphincter anomalies.

Associations with faecal incontinence

- Nocturnal enuresis and daytime detrusor overactivity. When all three occur together it is known as ‘dysfunctional elimination syndrome’ – perhaps linked through pelvic floor dysfunction. About 30% of children with FI also have nocturnal enuresis. Many have a family history of nocturnal enuresis.

- Behavioural problems are common but most are secondary to FI rather than the cause.

- Genetics: a family history of FI is common.

Pathophysiology

The majority of children with FI have significant faecal retention causing in turn, chronic rectal dilatation, hyposensitivity to stretching of the rectal ampulla, loss of the normal urge to pass stool and further retention. When the external anal sphincter relaxes, the stool accumulated in the rectal ampulla leaks. Unaware of the full rectum, the child may only sense the passage of stool by its contact with external skin, initiating an urgent rush to the toilet and a false impression that the child has ‘waited until the last minute’ – leading to inappropriate blaming.

Assessment of chronic constipation and faecal incontinence

History

- Timing of passing meconium stool (most <48 h).

- New onset of symptoms in child with previously normal bowel habit.

- Regression of motor skills.

- Painful or frightening precipitating events.

- Apprehensive behaviour such as toilet refusal, hiding while defecating.

- Faecal or urinary incontinence, day or night.

- Social/psychological impact of the problem.

Physical examination

- Abdominal examination for faecal loading.

- Growth – slow weight gain.

- Lower back, neurological assessment of lower limbs.

- Inspection of the anus and perianal skin for painful conditions (if it can be performed without adding to the child’s apprehension).

Investigation

- Abdominal radiograph and rectal examination most often do not change management, and are rarely required.

- Abnormal neurological findings are rare but must be investigated urgently.

Management

- Empty the bowel, keep it empty and provide soft lubricated stools.

- This needs to be maintained for a long period in order for the child to overcome the apprehension about defecation.

Disimpaction (for severe symptoms or to kick-start long-term management)

Rectally instilled medication (suppositories or enemas) may add to the child’s fearfulness. If using medications per rectum, consider sedation with nitrous oxide or midazolam (see Pain Management, chapter 4, p. 63).

Suggested medications (singly or in combination) include:

- Stool softener: paraffin oil (see notes below) 20–40 mL daily PO.

- Osmotic laxative: Macrogol 3350 (Movicol) sachets. One BD on day 1. Two BD day 2, three BD day 3, etc., increasing until desired result is achieved.

- Microlax enema 5 mL

- Gut stimulant, e.g. Senokot granules ½–1 teaspoon/day.

- For children refusing oral medication: sodium sulfate (Colonlytely) 1–3 L/day, via nasogastric tube.

Follow-on treatment

A long-term approach is needed, often spanning months to years. The physician, child and family need to work together and design an individualised treatment plan.

Behaviour modification is the mainstay of treatment. This involves regular sitting on the toilet and pushing, three times a day for 3–5 min. Use of a timer can be helpful to avoid arguments. Attention to the sitting position: feet supported, hips fl exed and encourage ‘bulging’ of the abdomen. Reinforce desired behaviour with stickers on an age-appropriate chart. Reward achievable goals such as good compliance with sitting programme rather than clean pants.

Medications are an adjunct to a toileting regimen. Paediatricians usually start with a single agent, most commonly paraffin oil or movicol.

- Stool lubricants/softeners:

– Paraffin oil 15–25 mL/d (see below).

- Osmotic laxatives:

– Movicol 1 sachet/day.

– Lactulose: <12 months, 5 mL/day; 1–5 years, 10 mL/day; >5–years, 15 mL/day.

- Stimulants:

– Senokot: 2–6 years, ¼–½ tsp/day; >6 years, 1 tab/d (7.5 mg).

– Bisacodyl: >4y – 1 tab/d (5 mg).

Paediatric follow-up is advisable. Consider referral to a sub-specialist continence clinic if combined faecal/urinary incontinence, suspected organic cause, complex or difficult cases.

Long-term use of most of these medications is safe and does not render the bowel ‘lazy’ or make the child ‘dependent.’ Only when defecation has been effortless for many months and toileting behaviour is consistent should one try to gradually withdraw adjunct medications.

Medication notes

- Paraffin oil is a stool lubricant that is colourless, odourless and almost tasteless. It is easily camoufl aged in many foods. In liquids it will fl oat and disperse into droplets without changing the taste of the liquid.

- Parachoc is paraffin oil with soluble fibre, fl avour and sweeteners which children often find too sweet. Agarol is similar, but with fl avourings that some will prefer. Parachoc carries a warning about risks of aspiration and lipoid pneumonia. Although this complication is not seen in practice it seems reasonable to avoid using Parachoc in children <6 months, and those with swallowing difficulty (lactulose may be a helpful alternative).

Nocturnal enuresis (NE) is (arbitrarily) defined as bedwetting in a child ≥5 years of age. It affects 20% of 5 year olds, 5% of 10 year olds and up to 1% of adults. Bedwetting in the absence of daytime urinary symptoms is called ‘monosymptomatic’ nocturnal enuresis (MNE) whereas if day symptoms occur it is ‘polysymptomatic’ nocturnal enuresis (PNE). Primary NE refers to a child who has never been dry for at least 6 months. Secondary NE refers to children who have become wet after a period of at least 6 months of dryness. Although secondary NE may suggest an organic or psychological cause, in practice most secondary NE is simply NE that never fully resolved.

Aetiology and pathophysiology

NE is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with variable penetrance. The pathophysiology involves a combination of:

- Poor arousal to stimulus of full bladder.

- Nocturnal polyuria – relative deficiency of vasopressin at night.

- Overactive bladder with reduced nocturnal functional bladder capacity.

Other factors may be involved in a way as yet unexplained. NE is more common in children with developmental delay, clumsiness, short stature or low birthweight. Most psychological problems in children with NE are likely to be the result of the wetting rather than the cause, and resolve with resolution of the wetting.

Children with PNE have daytime symptoms such as wetting, jiggling, urgency, frequent passage of small volumes of urine. Parents of such children often mistakenly think their child is lazy, preoccupied with other pursuits or simply habitually ‘waits until the last minute’. In fact they have an overactive detrusor muscle (irritable bladder) resulting in a small functional bladder capacity and small urgently voided volumes. The jiggling represents tightening of pelvic floor muscles in an attempt to defend against the forceful bladder contraction, so that wetting may be prevented or minimised. These children often have NE that is refractory to alarms and desmopressin, and persists beyond 10 years of age. Some also develop faecal incontinence (see p. 155).

Rare physical causes include UTI, diabetes mellitus/insipidus, epilepsy, ectopic ureter, obstructive sleep hypoventilation, neurogenic bladder. Sexual abuse will occasionally first present as NE.

Management

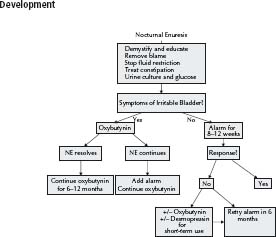

The spontaneous remission rate is only 15% per year. Those least likely to resolve spontaneously are those with PNE. Treatment should be offered to children ≥6 years for whom wetting has become a problem. See Fig. 13.1 for management algorithm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree