Sleep physiology

Sleep is a major challenge to the respiratory system, because it causes changes in respiratory mechanics and control of breathing leading to:

- Decreased ventilation.

- Decreased functional respiratory capacity (loss of intercostal muscle tone).

- Increased upper airways resistance (hypotonia of dilating muscles of upper airway).

- Depression of respiratory drive (REM > NREM > awake).

- Decreased response to hypoxia and hypercarbia.

Sleep stages and architecture

- Rapid eye movements (REM) and non rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. NREM sleep is further divided into four stages – NREM1 (light sleep) through to NREM4 (deep sleep).

- REM/NREM cycles occur at intervals of 60 min in the infant and lengthen to 90 min in the preschooler.

- Newborn infants sleep around 16 h/day, reducing to 14.5 h by 6 months and to 13.5 h by 12 months.

- Around 3 months of age the infant’s circadian rhythm is emerging, with sleeping patterns becoming more predictable and most sleep occurring at night.

- By 6 months of age most full-term healthy infants have the capacity to go through the night without a feed.

- Towards the end of the first year of life, the child’s sleep architecture becomes similar to that of an adult, with most of the deep sleep (NREM3/4) occurring in the first third of the night and REM sleep concentrated in the second half of the night.

- Infants who develop the ability to transition from sleep cycle to sleep cycle without parental assistance appear to sleep through the night.

One-third of families will complain of difficulties with their child’s sleeping patterns. Assessment should include:

- Detailed sleep history over 24 h, looking at how and where the child goes to sleep, frequency and character of wakings, snoring and daytime functioning.

- Sleep patterns during weekends/holidays and with different caregivers.

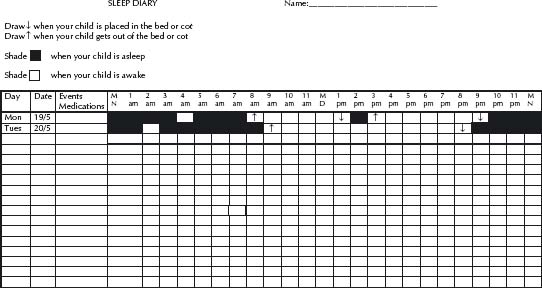

- A sleep diary may help clarify the situation (see Fig. 12.1).

- Family and social history to examine the presence of contributing problems, such as maternal depression, marital problems and drug or alcohol abuse.

- Exclude medical conditions contributing to disrupted sleep patterns such as obstructive sleep apnoea, asthma, eczema, nocturnal seizures, gastro-oesophageal reflux, otitis media with effusion, and nasal obstruction.

Bedtime struggles and night-time waking

For infants <6 months of age no interventions other than schedule manipulation (making sure the infant is not overtired and that adequate spacing between sleep times is provided) and anticipatory guidance are used. If parents want their infant to learn to settle by itself then they can try to leave the infant settled in its cot but leave before it is asleep. In the first 3 months of life some infants sleep better swaddled.

For older children, treatment plans must be individualised and adapted for each family.

Aetiology

- Sleep associations occur when a child learns to fall asleep in a particular way, so that every time the child has a normal arousal they wake up fully and are unable to put themselves back to sleep unless those particular conditions are set up again. Examples include rocking, feeding or falling asleep in the pram or car.

- Frequent feeding can cause wakings both by sleep associations and by the child developing a ‘learned hunger’ response. Some children can develop patterns that lead to consumption of large quantities of milk which affects not only their sleep patterns but eating during the day. Most healthy full-term babies can go without a night-time feed by 6 months.

- Erratic routine can contribute by inappropriate timing of naps and lack of a regular bedtime routine.

- Inconsistent limit setting in toddlers and preschoolers can exacerbate bedtime struggles and night-time wakings.

Management

- Detailed explanation about normal sleep and sleep cycles in a non-critical manner.

- Strategies to deal with inappropriate sleep associations all aim to provide the child with the opportunity to learn to fall asleep without parental assistance. Interventions range from extinction (letting the child cry it out), graduated extinction or controlled crying (checking the child at increasing periods of time until they fall asleep by themselves) to a more gradual approach whereby gradually all ‘props’ are removed.

- If frequent feeding is a problem discuss reducing the amount of fluid over 7–10 days and allowing the child to develop other ways to settle to sleep. Increasing the interval between breast-feeds, decreasing the amount of fluid in bottles or substituting water for milk/ cordial/juices are all useful strategies that parents can adopt.

- A regular day–night routine need to be established. An age-appropriate enjoyable bedtime routine should be introduced to help the child learn to anticipate going to bed. Sometimes a gate is useful when the child has graduated to a bed and the newfound freedom creates bedtime struggles.

- Sedative medication is not recommended for children <2 years. Promethazine or trimeprazine as single night-time dose – each 0.5 mg/kg (max 10 mg) – may be used in conjunction with behavioural techniques over a short time period or for parental respite.

Aetiology

Night-time fears may present in the preschool and school-age child with bedtime struggles and refusal to sleep by themselves. There may be a precipitant (frightening movie, bullying at school) or it may be a manifestation of an anxiety disorder.

Management

- Address separation issues for the child, which may include the introduction of a transitional object.

- Camper bed technique: a camper bed and a parent are moved into the child’s room. The parent spends the entire night in the child’s bedroom for 2 weeks helping them overcome their fears and gaining confidence in their own bed and room. This is often used in conjunction with a reward/sticker chart. The parent then gradually moves out of the child’s bedroom, once the child is sleeping through the night.

- Self-control techniques including relaxation, guided imagery and positive self-statements may also be used, again often in conjunction with reward/sticker chart.

- Make sure that the child is not in bed too early, allowing them the opportunity to further fuss and worry, which will interfere with sleep onset.

Night-time arousal phenomena and differentials

Aetiology

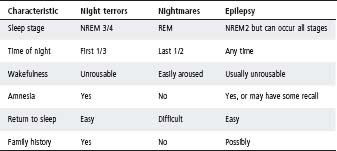

Sleepwalking and night terrors are disorders of arousal. They usually occur in the first third of the night during transition from NREM3/4 (deep sleep) to another sleep stage. They share common characteristics of the child being confused and unresponsive to the environment, retrograde amnesia, and varying degrees of autonomic activation (dilated pupils, sweating, tachycardia). See Table 12.1.

- Sleepwalking occurs at least once in 15–30% healthy children and is most common between 8 and 12 years. It can range from quiet walking, performance of simple tasks such as rearranging furniture or setting tables, to more frenetic and agitated behaviour.

- Night terrors are most common between 4–8 years and have a prevalence of 3–5%. They usually begin with a terrified scream and the child may either thrash around in bed or get up and run around the house. Efforts to calm the child often make the episode worse.

Differentials

- Nightmares generally occur during REM sleep and are thus more common in the second half of the night. They are vivid dreams accompanied by feelings of fear which wake the child up from sleep. They are most common in 3–6 year olds.

- Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (NFLE). This can present with brief repetitive stereotypical movements ± vocalizations throughout the night which can be associated with awareness by the patient. Alternatively NFLE can present with bizarre complex stereotypic dystonic movements which typically last <2 min.

Table 12.1 Characteristics of night terrors, seizures and nightmares

Management

- Obtain detailed history including the timing and duration of events, and the exact nature of movements (rhythmic or stereotypical) and behaviours.

- Completion of a sleep diary.

- A home video may be useful to aid diagnosis.

- All but NFLE are generally self-limiting. Explain, reassure and discuss safety issues.

- Avoid sleep deprivation as this can precipitate events. Ensure regular bedtime routines and sleep patterns.

- If events occur at a consistent time then scheduled awakening (waking the child 30 min before an event) may be useful.

- Sleep study may be required if events are very frequent, violent, atypical, or to assess contributing factors such as obstructive sleep apnoea.

- Medication is rarely needed. In situations where no aetiology has been found and there are very frequent and disruptive events, then low-dose clonazepam before bedtime may be useful for 4–6 weeks.

Snoring and sleep disordered breathing

- Sleep provides a physiological stress to breathing which can unmask respiratory difficulties that may not be apparent during wakefulness.

- Snoring is the most common symptom of sleep-disordered breathing in children and can be associated with primary snoring (PS) through to obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA).

- PS refers to snoring not associated with sleep or ventilatory disturbances; incidence up to 22% of children.

OSA

- OSA is defined as repeated episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction that disrupt normal ventilation and sleep.

- Incidence is 3% of children with peak incidence at 2–6 years due to adenotonsillar hypertrophy.

- Complications of severe OSA include growth failure and cor pulmonale, with milder OSA associated with impairment of behaviour and neurocognitive functioning.

- Symptoms include snoring, difficult or laboured breathing, apnoeas, mouth breathing, excessive sweating and restless or disturbed sleep. Children less commonly present with tiredness and lethargy.

- Increased risk of OSA is associated with:

– Adenotonsillar hypertrophy

– Obesity

– Syndromes (e.g. Down syndrome, Prader–Willi)

– Craniofacial abnormalities (e.g. Pierre–Robin, Apert)

– Mucopolysaccharidoses

– Achondroplasia and skeletal abnormalities

– Neuromuscular weakness (e.g. Duchenne)

– Hypotonia, hypertonia (e.g. cerebral palsy)

– Prematurity

– Previous palatal surgery (repaired cleft palate).

- Examination involves assessment of predisposing conditions and complications of OSA:

– Growth: either failure to thrive or obesity

– Craniofacial structure (retro/micrognathia, midface hypoplasia)

– Mouth breathing

– Nasal patency, septum, turbinates

– Tongue, pharynx, palate, uvula, tonsils

– Pectus excavatum

– Right ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary hypertension.

- Investigation by nasal endoscopy or lateral neck radiograph may have a place in assessing adenoidal size.

Management

- Although a decision regarding adenotonsillectomy is often made on history and examination, further investigations may be necessary and dependent on availability of local resources.

- Overnight oximetry is the most useful screening tool with the highest specificity. If there are repeated oxygen desaturations then a diagnosis of OSA can be made.

- Oximetry is limited in that it does not provide any information on the type of events associated with oxygen desaturations, CO2 retention or sleep disruption.

- Negative oximetry does not exclude OSA, but may provide reassurance that the child is unlikely to have severe OSA while awaiting further assessment.

- Overnight polysomnography (sleep study) continues to be the gold standard for diagnosis of OSA and should be performed if uncertainty persists, in high-risk children and children <2 years of age.

- Adenotonsillectomy is the first line treatment, being curative in majority of children. The role of adenoidectomy alone is unclear.

- Adenotonsillectomy is associated with a 2 week recovery period and there is a 2–3% risk of secondary haemorrhage especially 5–10 days postoperatively.

- Non-invasive ventilation (nasal CPAP) may be used for residual OSA, if there is a delay in surgery, or if surgery is contraindicated.

- Medical treatments of mild OSA include treatment of allergic rhinitis (intranasal steroids) and management of obesity.

Polysomnography involves the continuous and simultaneous recording of multiple physiological parameters related to sleep and breathing. Sleep studies are indicated for:

- Obstructive sleep apnoea; primary snoring vs sleep-disordered breathing.

- Monitoring non-invasive ventilation requirements.

- Excessive daytime sleepiness (include multiple sleep latency testing if narcolepsy suspected).

- Atypical night-time disruptions including very frequent or violent wakings.

- A full EEG montage is required if seizures are suspected.

- Periodic limb movement disorder.

USEFUL RESOURCES

- www.rch.org.au/ccch/profdev.cfm – [Professional development materials > Practice Resources Online] – RCH Community Child Health Centre. Evidence-based settling and sleep problems practice resource.

- www.sleephomepages.org – Extensive information and resource available to both clinicians and families.

- www.kidshealth.org/parent/growth – US online resource for parents with doctor-approved information about children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree