Infant distress (‘colic’)

A common research definition of colic is crying for >3 h per day, for ≥3 days per week for >3 weeks. However, parental tolerance of infant crying varies and it is more useful clinically to define the problem in terms of the parents’ concerns.

The typical clinical scenario is an extended period of distressed behaviour. The infant cries vigorously and the parents may interpret this as pain. There are usually repeated bouts with sudden onset. The legs are often drawn up and the face red. The worst period is typically in the late afternoon and early evening, but some infants seem to be irritable at any time of day.

It occurs equally in both sexes and in both breast-fed and formula-fed infants. It begins in the early weeks of life and abates by 3 months of age in 60% and by 4 months in >90% of infants.

The parents of infants who cry excessively are often exhausted and worried. Depression is common in mothers of irritable infants.

Assessment

A detailed history should be taken, noting:

- Temporal associations with feeds.

- Variation with contextual or environmental factors.

- Parental response (both affective and practical).

- Supports for the parents.

A detailed physical examination is important; particularly to reassure the parents that identifiable organic causes have been excluded. Physical causes are rare if the infant is thriving and developing normally.

History and examination should rule out conditions such as otitis media, refl ux oesophagitis (rare in the absence of vomiting) and raised intracranial pressure. Allergy to cow’s milk protein usually has associated features including vomiting, diarrhoea (sometimes with blood and/or mucus), failure to thrive or eczema. However, it can occasionally present with distressed behaviour alone. Lactose intolerance causes frothy stools with perianal excoriation and abdominal distension. Stool analysis is confirmatory with a low pH and presence of reducing substances.

Inquire about the mother’s supports, and evaluate for depressive symptoms. The 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (www.dbpeds.org/handouts) is a simple and well-validated screening instrument.

Management

- Reassurance that the infant is healthy is important and often extremely helpful.

- Explain that some infants appear excessively sensitive to both internal (e.g. overtiredness, hunger) and environmental stimuli in the early months of life, but that it will settle with maturation.

- Minimise environmental stimulation – low-level background noise, soft lighting and comfortable ambient temperature.

- Maintain predictable routines.

- Carrying the infant in a sling (snugly) is often helpful and allows the parents to free their hands. Patting, rocking, movement (e.g. swing, walking in pram), massage, warm baths, and a dummy may also be helpful.

- In persistent or severe cases a trial of cow’s milk protein elimination may be indicated. Mothers of breast-fed infants must carefully exclude all cow’s milk products from their diets and take calcium supplements. Formula fed infants can be given a 2–4 week trial of an extensively hydrolysed formula. Symptoms persist in a minority of highly allergic infants, in which case an elemental (amino acid based) formula can be tried. Refer also to chapter 19, Allergy and immunology, p. 231.

- A lactose-free formula can be tried in those infants with symptoms suggestive of lactose intolerance. Lactase tablets can be used for breast-fed infants, or expressed breast milk can be pre-treated with lactase drops.

- Medications such as antispasmodics and sedatives should not be used, and over-the-counter anti-colic preparations are rarely helpful. Antacids or ranitidine may be tried if the history suggests gastro-oesophageal refl ux (see chapter 27, Gastrointestinal conditions, p. 345).

- Encourage contact and support from extended family, friends, maternal and child health nurse, etc.

These are extremely frightening for parents, particularly initially. The peak incidence is at 1–3 years of age, although they generally begin in infancy and sometimes in the newborn period.

The most common type of breath-holding spell is a cyanotic spell. In response to relatively minor frustration or a painful stimulus (e.g. a knock to the head), the child cries briefl y before involuntarily holding the breath in expiration and becoming rapidly cyanosed. In some cases, loss of consciousness or even a brief hypoxic seizure results.

Pallid breath-holding spells are less common. The precipitating event is similarly minor and the child holds the breath and becomes markedly pale and limp. This is due to an excessive vagal response resulting in bradycardia or transient asystole.

Management

- Breath-holding spells need to be distinguished from seizures and this is usually possible on history. In breath-holding spells, cyanosis occurs before loss of consciousness whereas in seizures cyanosis occurs after loss of consciousness and onset of seizure activity.

- Place the child on its side until spontaneous recovery, which is usually rapid.

- Do not provide the child with excessive attention, which may promote secondary gain.

- Minimise unnecessary struggles with firm consistent behaviour management.

- Ensure the child is not iron deficient (dietary history ± laboratory testing) as this is associated with breath-holding spells.

It is developmentally normal for toddlers to express frustration as they strive for autonomy and some control over their world. From the second year of life most children will have temper tantrums, often persisting through to the preschool years. These tend to be more prominent in children with delayed speech development and associated frustration.

Management

- Assess contextual factors, e.g. avoid overstimulation or excessive fatigue.

- Assess the parents’ response.

- Behaviour modification techniques are most likely to be successful if applied consistently. This involves the same consequence being applied each time a particular behaviour occurs, across different environmental settings and caregivers.

- Consequences should be determined (with agreement of all caregivers) and explained to the child in advance. They should be applied immediately when the behaviour occurs, instituted as calmly as possible without discussion, negotiation or bargaining.

- Toddlers and preschool aged children generally respond to Pavlovian-style conditioning, i.e. positive reinforcement of socially acceptable behaviour and negative reinforcement of undesirable or unacceptable behaviour.

- Ignoring is effective for tantrums and other behaviours that don’t harm others. It involves the parents withdrawing any feedback that may be a positive reinforcer of the tantrum behaviour. The parent needs to stand some distance from the child, withdraw eye contact and not speak to the child at all. The parent should continue with what they were doing, or may need to walk away. Following the tantrum, acceptable behaviour should be praised. Some children may need reassurance after a period of prolonged or severe loss of control.When an ignoring programme is started the behaviour may escalate initially. However, if the parents can persist through this period, the frequency of tantrums will decrease.

Aggression/oppositional-defiant behaviour

Most children will exhibit some defiant and non-compliant behaviours as they negotiate progressive developmental stages. Parents may seek help when relationships within the family are strained or the child’s behaviour is extreme, antisocial, or impairs learning and social development.

Symptoms vary with age and sex. Young children particularly display verbal and physical aggression when unhappy or frustrated. Underlying contributing factors such as developmental and learning disabilities, family and parenting problems and the infl uence of violent electronic media need to be considered in a biopsychosocial model.

Management

Positively reinforce acceptable behaviour

Parents should be encouraged to ‘catch the child being good’, noticing and rewarding acceptable behaviour. Encourage abundant use of praise.

Structured reward systems are often extremely helpful for children from about 2.5 to 5 years of age. An example of this is for the child to make a colourful ‘Big Boy’ or ‘Good Boy’ chart. The child is rewarded with stickers (0–2/day) and once they accumulate five stickers they earn a special surprise in the form of a lucky dip selected from a box. Do not use food or sweets as rewards. Healthy competition can be set up with the model sibling, to increase motivation. Stickers should not be removed from the chart as punishment (rewards and punishments should be separate).

Ignore minor irritating behaviours

In many families a great deal of energy is spent arguing about relatively inconsequential behaviours such as whingeing, nagging or not tidying up. This is not sustainable, as the parents usually become exhausted. It is preferable to save energy for serious indiscretions.

Serious oppositional behaviours

Serious behaviours, including hitting or kicking somebody or damaging property, must be managed with consistent consequences.

Toddlers and preschool age children generally respond very well to time out when used consistently. This involves calmly and immediately placing the child in a chair or in their room for a timed period of 1 min per year of age, for certain predetermined, defined behaviours. If they are calm at the end of the time they can come out, otherwise the clock starts again. Most children learn to abide by time-out rules if used consistently, as they recognise they need containment.

For school-age children withdrawal of privileges (e.g. TV, video games) is generally the best strategy. Again this should be introduced immediately after the behaviour occurs and applied for a brief period only (e.g. 1–2 days).

Smacking should be discouraged as it models violence and is usually not effective. Serious antisocial or delinquent behaviours such as frequent high-level violence, cruelty to animals, arson or repeated stealing are indicators of a significant conduct disorder and warrant referral to a child and adolescent mental health service. It is important, however, to recognise that isolated incidents are common and not necessarily indicative of severe psychopathology.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the term currently applied to a range of childhood behaviours sharing the core features of poor impulse control and limited sustained attention to tasks, often with motor hyperactivity. Common associated features include oppositional defiant behaviour, anxiety, learning difficulties and tics.

The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD are provided in Table 11.1. Most children with ADHD have the combined type. The predominantly inattentive subgroup often present later with academic difficulties, as they do not generally display disruptive behaviour.

Assessment

- History: A detailed history is critical, focusing on attachment, early development, social skills and academic progress. The timing and nature of initial concerns along with secondary effects such as depression, low self-esteem and social ostracism should be noted. It is important to identify the child’s strengths as well as their weaknesses. Standardised behaviour rating scales, completed by parents and teachers (e.g. Connors, Achenbach), are helpful.

- Physical examination: Should focus on neurodevelopment assessment including fine and gross motor coordination, visual-motor integration, auditory and visual sequencing, etc.

- School reports.

- Psychoeducational assessment: Children with significant learning difficulties should be referred to an educational psychologist for a formal assessment to identify their learning strengths and weaknesses. This can be arranged through the education department (via the school) or privately.

- Audiology including auditory processing assessment is often helpful. Other investigations are not usually required.

Management

Children with ADHD have multiple special needs and difficulties and the priorities often change over time. The child, family and school need sustained and skilled support over many years. This requires the doctor to work in collaboration with other health, educational and community professionals. A multimodal strategy is required.

Table 11.1 DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD

| A Either 1 or 2 |

| 1. Inattention At least six of the following nine symptoms have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level: |

| • Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in school work, work or other activities |

| • Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities |

| • Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly |

| • Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork chores or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behaviour or failure to understand instructions) |

| • Often avoids or dislikes tasks (such as schoolwork or homework) that require sustained mental effort |

| • Often has difficulty organising tasks or activities |

| • Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g. school assignments, pencils, books, tools or toys) |

| • Often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli |

| • Often forgetful in daily activities |

| 2. Hyperactivity/Impulsivity At least six of the following nine symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level: |

| Hyperactivity |

| • Often fidgets with hands or feet and squirms in seat |

| • Often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations in which remaining seated is expected |

| • Often runs about or climbs excessively in situations where it is inappropriate (in adolescents or adults may be limited to feelings of restlessness) |

| • Often has difficulty playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly |

| • Is often on the go and acts as if driven by a motor |

| • Often talks excessively |

| Impulsivity |

| • Often blurts out answers to questions before the questions have been completed |

| • Often has difficulty awaiting turn |

| • Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g. butts into conversation or games) |

| B Onset no later than 7 years of age |

| C Symptoms must be present in two or more situations (e.g. at school, at home and/or at work) |

| D The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning |

| E Does not occur exclusively during the course of a pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder, and is not better accounted for by a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder |

Behaviour modifcation

- The methods described previously under aggression/oppositional-defiant behaviour (p. 139) are generally helpful.

- Parents and teachers need to apply structured behavioural modification strategies as consistently as possible. Predictable routines are required both at home and at school.

Educational strategies

- An individualised plan should be developed to optimise learning and promote appropriate behaviour.

- Classroom adaptations include seating the child at the front of the classroom near a good role model and using written lists and other visual prompts. Some children need individualised instructions and encouragement to complete tasks, with increased adult one-to-one supervision such as a teacher’s aide. Frequent breaks with the opportunity to move around the classroom help the child remain on task. Tasks such as collecting lunch orders similarly break up the work and are also good for self-esteem.

- Clear rules and predictable routines are important. Positive reinforcement should be provided for acceptable behaviour.

Medication

Stimulants

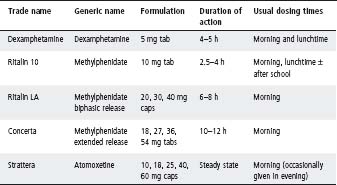

Psychostimulant medication is the single most effective intervention for children with ADHD (see Table 11.2). It is effective in about 75% of cases, helping children to control antisocial verbal and physical impulses and sustain attention to tasks to enable work completion and academic success nearer their potential. Secondary benefits, including improved peer status, family functioning and self-esteem, accrue over time. Extended release stimulant preparations are now available, avoiding the need for a dosing at school (Table 11.2).

The main side effect of stimulants is appetite suppression. Weight, height and blood pressure need to be monitored regularly.

In most states of Australia the prescribing of stimulants is restricted to paediatricians, neurologists and child psychiatrists.

Other medications

A number of other medications are useful in some children with ADHD. These include:

- Atomoxetine, a selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, which is given once daily.

- Clonidine, which can help smooth out explosive behaviour and assist with sleep onset. If clonidine is used in combination with a stimulant, twice-daily dosing is preferable and the total daily dose should not exceed 200 mcg.

- Antidepressants (tricyclics, SSRI, SNRI) are particularly beneficial if there is associated anxiety.

Other strategies

The parents of children with ADHD commonly try a range of unproven complementary therapies, including behavioural optometry, cerebellar training exercises, chiropractic, etc. There is no evidence that these interventions are helpful and some are expensive and/or potentially harmful. Anecdotally, elimination of synthetic food colourings and preservatives is beneficial in a small number of children.

Table 11.2 Medications for ADHD

Note: All items are available on the PBS via an authority prescription. If the main impairing symptom is inattention then medication may be needed only for school +/− activities outside of school with high concentration demands. Drug holidays (planned treatment interruption over school holidays) are not necessary for most children; consider if suboptimal linear growth.

Prognosis

Most children with ADHD will continue to have some difficulties through adolescence and into adulthood, although many develop good compensating strategies and function very well. A significant minority suffer long-term complications including academic underachievement, school drop-out, delinquency, vocational disadvantage and relationship difficulties. Children with ADHD treated with stimulant medication appear to be less likely to develop substance abuse in adolescence and adult life than those left untreated.

There are many reasons why a child may experience learning difficulties, and often multiple factors are involved. These include specific learning disabilities (commonly language–literacy based), intellectual disabilities, attentional deficits, sensory impairments (hearing, auditory processing, vision), emotional disturbance, chronic illness, family and social difficulties, and suboptimal teaching or educational environments. A specific learning disability is defined as a discrepancy between a child’s intellectual ability and their academic achievement. See also chapter 14, Developmental delay and disability.

Assessment

- Obtain information from both parents and teachers.

- Obtain previous school reports.

- Formal educational psychology assessment.

- Neurodevelopmental assessment undertaken by a developmental paediatrician is important in identifying areas of difficulty such as visuomotor integration, short-term auditory memory, motor planning and coordination, and fine motor skills.

Management

- The doctor has an important role in excluding treatable contributing medical factors (e.g. sleep deprivation, iron deficiency, ADHD, depression, epilepsy), as well as advocating for the child.

- Liaise closely with the school to ensure appropriate assessments are undertaken and that an individualised educational plan is devised and reviewed periodically, taking into account the child’s special needs.

- In severe cases an application for disability programme funded assistance should be made via the school to the education department.

- Some children benefit from remedial tuition either within or outside school hours. It is important for parents not to overburden children, who also need normal recreational time.

- Parents need support in understanding their child’s potential and ways in which they can help optimise their child’s learning. Identifying and enhancing the child’s strengths is important in maintaining self-esteem.

Language delay/impairment can involve receptive skills (ability to understand spoken language), expressive skills (language production) or both (Table 11.3). Articulation/phonological problems may also occur, resulting in reduced speech intelligibility.

Background

- Approximately 20% of 2 year olds are considered late talkers, i.e. children with smaller than expected expressive vocabularies (<50 words and few or no word combinations).

- Children with language delay at 1 and 2 years are at risk of later language impairment, but only 5–8% of 4–5 year olds have language impairment.

- Although some children spontaneously recover or ‘grow out’ of their early delay, it is not possible to predict with any certainty which children will have persistent speech and language problems.

- Delay in speech development may be specific, or may coexist with more general language problems. Speech and language delays may also be isolated, or may refl ect a delay in the child’s cognitive development.

- Children with autism may present with concerns regarding speech and language development. These children have distinct early communicative, social and behavioural difficulties that differ from children with primary language impairment (see chapter 14, Developmental delay and disability, p. 172).

Prognosis

Preschool children with persistent speech and language impairment tend to have:

- Learning and social difficulties when starting formal schooling.

- Increased risk for later literacy problems.

- Increased rate of emotional and behavioural disorders.

These problems may persist into adolescence and adulthood and affect employment opportunities.

Factors raising concern about speech and language

- Parental report of concern regarding speech and language development.

- History of hearing loss.

- Family history of speech and language difficulties.

- Receptive and expressive language skills both delayed.

- Concern about other aspects of development and lack of developmental progress (Table 11.3).

- Autistic features, for example, poor social interactions, limited use of gesture/facial expressions, stereotypic and repetitive behaviours, ‘in their own world’.

- Concern regarding general stimulation received.

- Parental report of regression in babbling or language.

Table 11.3 Speech and language milestones: indicators of concern

| Age (years) | Reason for concern |

| 6 months | No response to sound, not cooing, laughing or vocalising |

| 12 months | Not localising to sound or vocalising. No babbling or babbling contains a low proportion of consonant vowel babble (e.g. baba). Doesn’t understand simple words (e.g. ‘no’ and ‘bye’), recognise names of common objects or responds to simple requests (e.g. ‘clap hands’) with an action |

| 18 months | No meaningful words except ‘mum/dad’. Doesn’t understand and hand over objects on request |

| 2 years | Expressive vocabulary <50 words and no word combinations. Cannot find 2–3 objects on request |

| 3 years | Speech is not understood within the family. Not using simple grammatical structures (e.g. tense markers). Doesn’t understand concepts such as colour and size |

| 4 years | Speech is not understood outside the family. Not using complex sentences (4–6 words). Not able to construct simple stories |

| 5 years | Speech is not completely intelligible. Does not understand abstract words and ideas. Cannot reconstruct a story from a book |

Management

- Assess other areas of the child’s development, if uncertain or concerned refer to a specialist. Formal cognitive assessment may be needed.

- Exclude hearing loss as a contributing factor by referral to an audiologist.

- Referral to a speech pathologist is recommended as early as possible. Don’t delay! Speech pathologists may decide to ‘watch and wait’ but only after they have considered factors such as the child’s speech and language profile, environmental factors, family history, developmental history and progress to date.

- In cases where regression in language is suspected, refer promptly to a paediatrician. In a child <2 years, a sign of regression may be losing a number of words that had been previously well-established, used spontaneously and frequently for at least 4 weeks.

Stuttering is a disorder that affects the fl uency of speech production. It has a strong genetic link, with 50–75% of people who stutter having at least one relative who also stutters. Stuttering is now considered to be a developmental anomaly rather than a psychological disorder.

About 5% of children start to stutter, usually during the third and fourth year. Stuttering may occasionally appear for the first time in school aged children and even more rarely in adulthood. Stuttering in children is more amenable to treatment than stuttering in adults. The period of time that has lapsed since the onset of stuttering is a strong predictor, with little chance of natural recovery in children >9 years old. More girls recover naturally than boys. Family history of recovery may increase the child’s chance of recovering naturally.

Speech is disrupted by abnormal repeated movements of the speech mechanism, such as ‘I w-w-w-w-w-was saying …’, and fixed postures of the speech mechanism during which speech stops.

Many features of stuttering are superfl uous behaviours, such as body tics and abnormal patterns of speech respiration.

Management

- Do not ignore the stutter.

- If stuttering persists for ≥6 months, refer to a speech pathologist. Treatment of preschool stuttering should be undertaken by speech pathologists trained in the Lidcombe programme, which has been shown to be efficacious in this age group.

USEFUL RESOURCES

- www.dbpeds.org – Developmental and Behavioral Paediatrics Online. Fantastic website linked with the American Academy of Paediatrics, with abundant helpful, practical information for doctors and families.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree