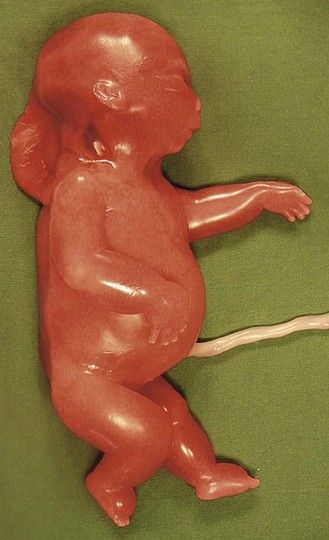

Figure 7.1 Fetus with trisomy 21.

Despite the increase in the early diagnosis of this pathology, certain women—voluntarily or otherwise—have not had early tests for this condition. In questioning the patient, we should seek out elements to help direct our research: an old or very young maternal age; an inadequate dating for the US; serum markers not performed.

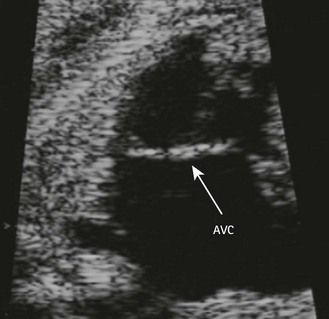

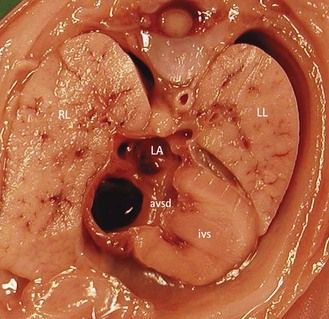

The type of cardiopathy can point us in the right direction. It is often primarily a cardiopathy of the atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) spectrum, whether complete AVSD (Figs 7.2 and 7.3) to linear insertion of atrioventricular valves (LIAVV) without defect (Figs 7.4 and 7.5);3,4 trisomy 21 should also be considered with tetralogy of Fallot.

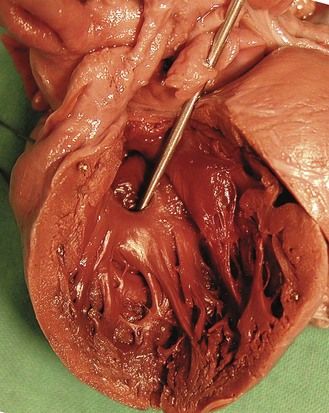

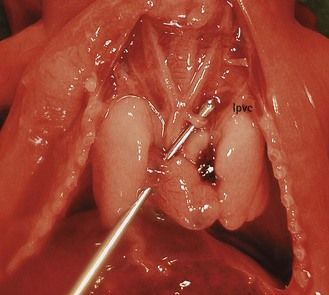

Figure 7.2 Anatomic thoracic four-chamber view: complete AVSD. The interventricular septum (IVS) is short and thick.

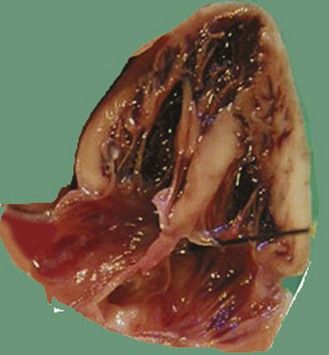

Figure 7.5 Apical anatomic four-chamber view of a LIAVV without defect. The needle is under the septal tricuspid leaflet which is not stuck to the IVS.

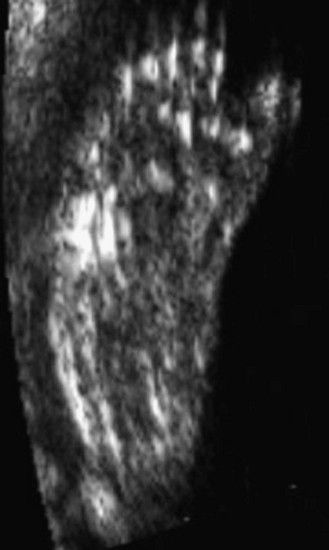

The examination looks for extracardiac anomalies or malformations:5 a flat profile with shortening or even the absence of the fetal nasal bone (NB) and a filling of the small nasofrontal space; small ears; a thick nape of the neck or nuchal thickening (Fig. 7.6); a brachy- and even an amesophalangy of the fifth digit (Fig. 7.7); and a spacing of the big toe (Fig. 7.8). All these characteristics are more evocative than images of a pyelectasis, a suspicion of esophageal atresia (Fig. 7.9), or a unique umbilical artery (UUA).

Trisomy 18 (T18; Edwards syndrome)

This occurs in 1 in 1800 pregnancies.

Trisomy 18 is more often associated with outlet cardiopathies; it is first considered when the cardiopathy (Fig. 7.10)6 is associated with intrauterine retarded growth (IURG) (Fig. 7.11). Nearly always present, IURG should not always be attributed to a possible coexistent vascular pathology.

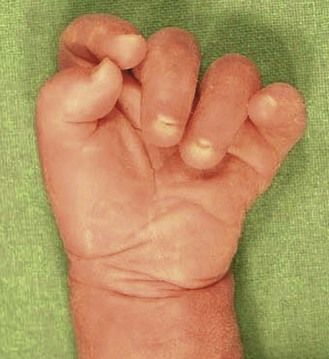

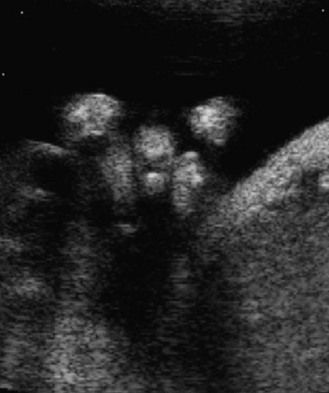

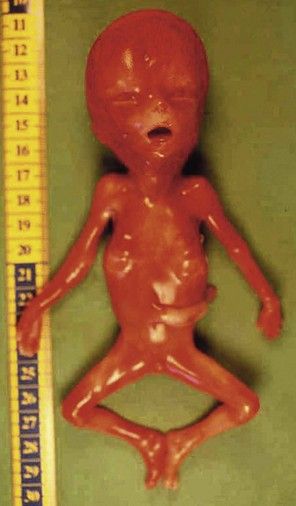

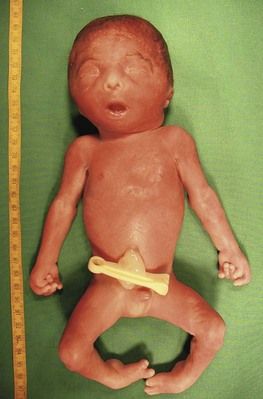

Figure 7.11 Week 27 of a T18 pregnancy. The fetus has the development of only 24 weeks demonstrating IURG. Notice the dysmorphia, the clenched hands, and the club-foot.

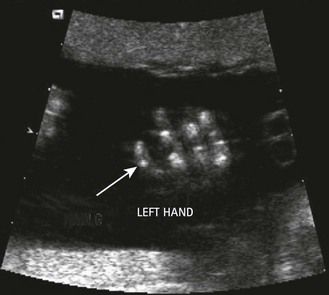

The discovery of clenched hands (Figs 7.12 and 7.13) (with the impossibility of obtaining an image with the hands open), an aplasia of the radial ray responsible for “boot hands”, a small exomphalos, spina bifida, or a diaphragmatic hernia all lead us to this diagnosis. But as in all chromosomal anomalies there exist minor forms of this pathology which support the principle of systematically asking for a karyotype faced with any and all cardiopathies.

Trisomy 13 (T13; Patau syndrome)

This occurs in 1 in 5000 pregnancies.

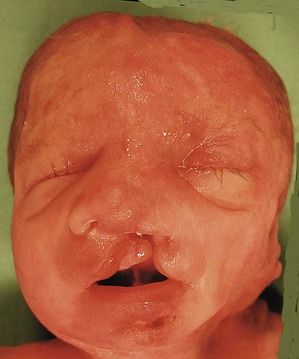

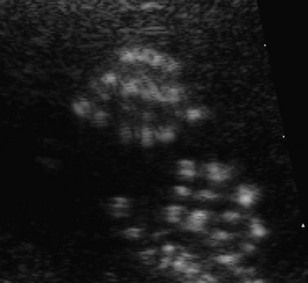

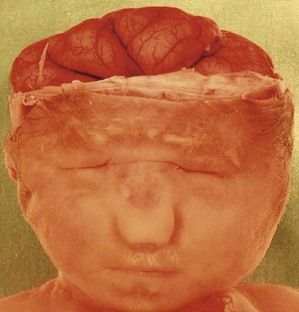

The pathognomonic triad of a labiopalatine cleft (Fig. 7.14), holoprosencephaly (Fig. 7.15), and hexadactyly (Figs 7.16 and 7.17) is not always seen together. In the absence of all of these signs the diagnosis can be directed by the type of cardiopathy: frequency of the AVSD or a common arterial trunk (CAT) with displastic valves (hyperechogenic).

Figure 7.15 A lobar holoprosencephaly in a T13 fetus. Notice the microphthalmos, the unique naris, and the small mouth. This demonstrates the saying that the “face reflects the brain”.

Next to these three frequent anomalies—whose minor forms we should be aware of—two other anomalies seldom go unnoticed at 12 gestational weeks. More than NT (Fig. 7.18), we often have to deal with a hygroma with anasarca in Turner’s syndrome or a very early IUGR in triploidy.

Turner syndrome

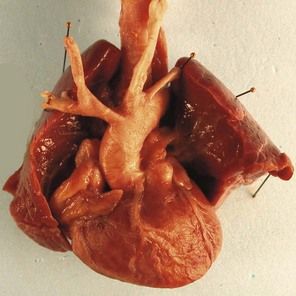

Turner syndrome (Fig. 7.19) is with a karyotype primarily of 45X0. Its early diagnosis is frequently made when faced with a hygroma which can be differentiated from an augmentation of the NT at 12 gestational weeks. This could be a description of hydrops with anasarca. The diagnosis of the characteristic cardiopathy will only be made in fetal pathology; it is a stenosis of the horizontal section of the aorta7 in a female fetus (Fig. 7.20). Approximately 95% of pregnancies with a fetus having 45X0 are spontaneously interrupted and stillborn.

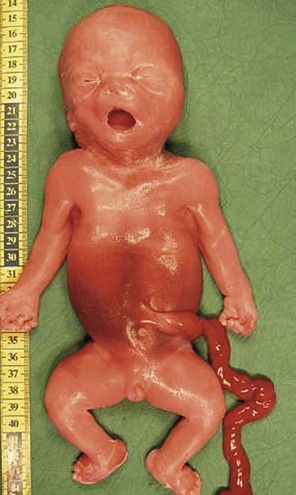

Figure 7.19 Turner syndrome showing Bonnevie–Ullrich syndrome (hygroma, anasarca, and generalized edema) with primarily a 45X0 karyotype.

Triploidy

This is a pathology8 that is often proposed when we see an early, major form of IURG, and which is frequently taken to be an error of dating at the beginning of pregnancy. We note that there is often a disproportion between the head and the body, thin members with a large head (Fig. 7.21). In certain forms, we equally observe a highly suggestive fetus–placenta disequilibrium. Here, associated with a severe type of CTC in the form of a tetralogy of Fallot (Fig. 7.22), we see syndactyly III–IV (Fig. 7.23), characteristic, but difficult to see on US.

The karyotype is known to be normal

This situation is becoming more frequent.9 Attention should be paid to two elements.

First, the karyotype can be made using a culture from different cells (biopsy of the trophoblast, cells from the amniotic liquid, or fetal blood) which can produce discordance in the results, for example by disregarding a tetrasomy 12p10 in a fetus appearing quite similar to Fryns syndrome (Figs 7.24 and 7.25). (If the karyotype seems to be normal in fetal blood, the tetrasomy appears only when requested on an investigation of the amniotic fluid.)

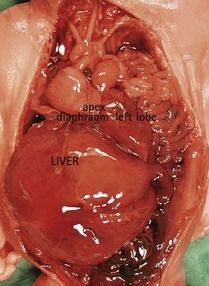

Figure 7.25 The same fetus as in Figure 6.24 with the viscera showing a diaphragmatic hernia. A new karyotype carried out using the amniotic fluid showed a 12p tetrasomy.

In addition, certain minor pathologies of the karyotype11 can only be suspected after a re-examination of the initial karyotype, made after the discovery of a cardiopathy. Finally, an indication for specific research such as exploring a 4p deletion, for instance (Fig. 7.26), or even the possibility of a new karyotype, can be considered.

Second, the “standard” karyotype only explores the chromosomal pathologies of number. The discovery of a CTC leads us to request a complementary research in the 22q11 chromosomal deletion. This deletion will primarily be found in cases of IAA of the B type (Fig. 7.27), or with a pulmonary atresia with opened septum (PA with OS) with aortic–pulmonary collaterals (main aorta–pulmonary collateral arteries: MAPCA), or even a CTC with a right aortic arch (Fig. 7.28) and/or the absence of the ductus arteriosus (DA). We equally find other anomalies: hypo- to athymism; cleft palate or cleft lips; or frequent renal anomalies (in 29% of the cases),12 which can rapidly hamper the examination by creating oligohydramnios. The dysmorphism (Fig. 7.29) is difficult to appreciate, except in those instances where there is a cleft. As for a thymic hypoplasia, it is easier to appreciate on the fetal–pathologic examination (Fig. 7.30) than with US.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree