Thomas G. Stovall

Hysterectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures performed. After cesarean delivery, it is the second most frequently performed major surgical procedure in the United States (1). According to the National Hospital Discharge survey, the rate of hysterectomy during the 5-year study period was 5.4 per 1,000 women per year in 2000 and declined to 5.1 per 1,000 per year in 2004. These data do not represent hysterectomies performed in ambulatory settings. The highest rate of hysterectomy is between the ages of 40 and 49 years with an average age of 46.1 years (1). The highest rates of hysterectomy are for women living in the southern United States and they occur at a younger age. The lowest rates are consistently in the northeastern portion of the United States. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with increased hysterectomy rates (2). Hysterectomy rates are higher for black women (3). Reports on the effect of physician gender conflict with recent data shows no overall impact (4). Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy decreased between 2000 and 2004 from 53.8% to 49.5% (1). The frequency was the highest with abdominal hysterectomy and the lowest with vaginal hysterectomy.

Indications

The indications for hysterectomy are listed in Table 24.1. Uterine leiomyomas are consistently the leading indication for hysterectomy. As expected, the indications differ with the patient’s age (1). Hospitalization rates for hysterectomy in women between the ages of 15 and 54 years decreased from 1998 to 2005 for all indications except for menstrual disorders (5).

Table 24.1 Indications for Hysterectomy (Percentage): United States 2000–2004

| Uterine leiomyoma | 40.7 |

| Endometriosis | 17.7 |

| Other | 15.2 |

| (includes cervical dysplasia and menstrual disorders) | |

| Uterine prolapse | 14.5 |

| Cancer | 9.2 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 2.7 |

| From Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. Obstet Gynecol 2008;34.e1–e7, with permission. | |

Leiomyomas

The proportion of hysterectomies performed for leiomyomas decreased over time (1) (see Chapter 15). Fertility-preserving surgical management (myomectomy) is possible in most patients with leiomyomas. The decision to perform a hysterectomy for leiomyomas is usually based on the need to treat symptoms—abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, or pelvic pressure. Other indications for intervention have included “rapid” uterine enlargement, ureteral compression, or uterine growth after menopause. There is no clearly reproducible definition of rapid growth. The concept of rapid growth was challenged because these patients did not demonstrate clearly malignant conditions (6). Refuted reasons for hysterectomy in patients with leiomyomas are size greater than 12 weeks of gestation without symptoms, inability to palpate the ovaries on bimanual examination, and increased morbidity at hysterectomy with increased uterine size. If the procedures are performed abdominally, there is no difference in surgical morbidity between patients with a 12-week-sized uterus and those with a 20-week-sized uterus (7). Therefore, hysterectomy for leiomyomas should be considered only in symptomatic patients who do not desire future fertility (7).

To reduce uterine size before hysterectomy, patients with large leiomyomas may be pretreated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (8,9). In many cases, the reduction of uterine size is sufficient to permit vaginal hysterectomy when an abdominal hysterectomy would otherwise be necessary. In one prospective trial, premenopausal patients with leiomyomas the size of 14 to 18 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive either 2 months of preoperative depot GnRH agonist or no GnRH agonist (8). Treatment with a short course (8 weeks) of leuprolide acetate before surgery enabled the procedures to be converted safely from an abdominal hysterectomy to a vaginal hysterectomy (9). This preoperative regimen was associated with a rise in hematocrit before surgery and a shorter hospital stay and convalescent period because patients were more likely to have a vaginal rather than an abdominal hysterectomy.

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Excessive uterine bleeding is the indication for about 20% of hysterectomies. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding assumes abnormal bleeding without an obvious anatomic cause (see Chapter 14). Anovulatory uterine bleeding is typically associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a condition in which anovulatory cycles are common. The bleeding can be controlled by medical intervention with progestin, estrogen, or a combination of progestin and estrogen given as oral contraceptives. Ovulatory abnormal uterine bleeding can be controlled by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, hormonal intervention, tranexamic acid, or the levonorgestrel intrauterine device. In these patients, endometrial sampling should be performed before hysterectomy (10). Dilation and curettage is not an effective means of controlling bleeding and is not necessary before hysterectomy. Hysterectomy should be reserved for patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate medical therapy. Alternatives to hysterectomy (e.g., endometrial ablation or resection) should be considered in selected patients because these operations may be cost-effective and have a lower morbidity rate. However, in a clinical trial that randomized endometrial ablation to hysterectomy, 29% of patients assigned to the ablation underwent hysterectomy by 60 months (11).

Intractable Dysmenorrhea

About 10% of adult women are incapacitated for up to 3 days per month as a result of dysmenorrhea (see Chapter 16) (12). Dysmenorrhea can be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents used alone or in combination with oral contraceptives or other hormone agents to reduce or ablate menstrual flow (12). The levonorgestrel intrauterine device effectively reduces dysmenorrhea symptoms. Hysterectomy is rarely required for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. In patients with secondary dysmenorrhea, the underlying condition (e.g., leiomyomas, endometriosis) should be treated primarily. Hysterectomy should be considered only if medical therapy fails or if the patient does not want to preserve fertility (12).

Pelvic Pain

In a review of 418 women in whom hysterectomy was performed for a variety of nonmalignant conditions, 18% had chronic pelvic pain. Preoperative laparoscopy was performed in only 66% of these patients. After hysterectomy, there was a significant reduction in symptoms that was associated with an improvement in the patient’s quality of life (13). In a review of 104 patients who underwent hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain that was believed to be of uterine origin, 78% experienced improvement in their pain after follow-up for a mean of 21.6 months (14). However, 22% of patients had no improvement in or exacerbation of their pain. Hysterectomy should be performed only in those patients whose pain is of gynecologic origin and does not respond to nonsurgical treatments (12) (see Chapter 16).

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

In the past, hysterectomy was performed as primary treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. More conservative treatments, such as laser or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), can be effective in treating the disease, making hysterectomy unnecessary in most women with these conditions (see Chapter 19). For patients with recurrent high-grade dysplasia who do not desire to preserve fertility, hysterectomy may be an appropriate treatment option. After hysterectomy, these patients are at increased risk for vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia.

Genital Prolapse

Hysterectomy for symptomatic genital prolapse accounts for about 14.5% of hysterectomies performed in the United States (1). Unless there is an associated condition requiring an abdominal incision, vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred approach for genital prolapse. Uterine prolapse typically is not an isolated event and most often is associated with a variety of pelvic support defects. Each defect must be corrected to optimize the surgical outcome and decrease the risk of developing future pelvic support defects.

Obstetric Emergency

Most emergency hysterectomies are performed because of postpartum hemorrhage resulting from uterine atony. Other indications include uterine rupture that cannot be repaired or a pelvic abscess that does not respond to medical therapy. Hysterectomy may be required for patients with placenta accreta or placenta increta.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease can be treated successfully with antibiotics. The uterus, tubes, and ovaries should not be removed in a patient with pelvic inflammatory disease that is refractory to intravenous antibiotic therapy (see Chapter 18). Whether one proceeds with conservative surgical management, abscess drainage, or organ removal is a subjective decision that must be based on the individual. If accessible, some pelvic abscesses may be drained successfully by percutaneous catheter drainage guided by ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) scanning. Surgical intervention is necessary if the patient has acute abdominal findings associated with peritonitis and signs of sepsis in the presence of a ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess. For the patient who desires future fertility, consideration should be given to unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or partial bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy. For the patient in whom bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is required, the uterus can be left in place for possible ovum donation and in vitro fertilization.

Endometriosis

Medical and conservative surgical procedures are successful for treatment of endometriosis (15). Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with or without hysterectomy, should be performed only in patients who do not respond to conservative surgical (resection or ablation of endometriotic implants) or medical therapy (see Chapter 17). Most patients with endometriosis who require hysterectomy have unrelenting pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea. Other less common situations include patients who do not desire future fertility and who have endometriosis involving other pelvic organs, such as the ureter or colon. Hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy provides significant pain relief to the majority of patients. At the time of hysterectomy for endometriosis, consideration should be given to conserving normal ovaries (16).

Pelvic Mass or Benign Ovarian Tumor

If a pelvic mass is palpated on pelvic examination, a transvaginal ultrasound should be performed (see Chapter 14). If the mass is suspicious, appropriate consultation with a gynecologic oncologist is recommended. Benign ovarian tumors that are persistent or symptomatic require surgical treatment. If the patient desires fertility, the uterus should be conserved. If fertility is not an issue or if the patient is perimenopausal or postmenopausal, a decision must be made regarding whether the uterus should be removed. In one study, 100 patients who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy plus hysterectomy for benign adnexal disease were compared with a group of risk-matched women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy for the same indication (17). There was a significant increase in operative morbidity, estimated blood loss, and the length of hospital stay for patients in whom hysterectomy was performed.

Preoperative Considerations

The preoperative discussion should include an informed consent that documents the options, risks, benefits, outcome, and personnel involved with the procedure. The medical record should reflect the completion of childbearing and that adequate trial of medical or nonsurgical management was offered, attempted, or refused.

Health Assessment

An assessment of a patient’s health status is important in order to obtain an optimal outcome after hysterectomy for benign disease. There are no routinely recommended tests, although individual hospitals may have their own requirements. The patient should be evaluated for risk factors associated with venous thromboembolic events (18). Age, medical history, such as inherited or acquired thrombophilias, obesity, smoking, and hormonal medication, including contraceptives or hormone therapy, may increase the risk.

It is important to assess and correct underlying anemias before surgery. Blood product use can be minimized with preoperative iron supplementation or use of GnRH agonists.

Hysterectomy versus Supracervical Hysterectomy

There is a trend toward retention of the cervix at hysterectomy because of the perception that several outcome parameters, including sexual function and pelvic support, are better after a supracervical hysterectomy. Three prospective randomized clinical trials as summarized in a Cochrane review challenge this perception (19). There was no evidence to support the concept that leaving the cervix improves sexual function or lower rates of incontinence or constipation. All of these studies included hysterectomies that were performed by laparotomy. Surgical time was decreased by approximately 11 minutes.

This decreased surgical time may be more significant for laparoscopic cases, as the most difficult part of the surgery is the detachment of the cervix from the lateral ligaments and from the vagina. This is where most ureteral injuries occur during laparoscopic hysterectomy. This advantage should be balanced with the potential risk of ongoing cyclic bleeding from the cervix that is reportedly between 5% to 20% from the randomized clinical trials and 19% from a prospective observational laparoscopic trial (20). With conservation of the cervix, the patient should be told there is a potential 1% to 2% risk for reoperation to remove the cervix and that trachelectomy is associated with a risk of intraoperative complications. Patients with suspected gynecologic cancers or cervical dysplasia are not candidates for supracervical hysterectomy.

Prophylactic Salpingo-oophorectomy

The decision to remove the ovaries and tubes should be based on assessment of risk and not the route of hysterectomy (21). Premenopausal women who are at average risk of ovarian cancer (approximate lifetime risk of 1.4%) should be considered for ovarian preservation when they are undergoing hysterectomy for benign conditions where the ovaries and fallopian tubes are healthy (22). Parous women who have used oral contraceptives may have a substantially lower risk (22). Elective removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes has declined since 2002 (23).

Salpingo-oophorectomy is performed prophylactically to prevent ovarian cancer and to eliminate the potential for further surgery for either benign or malignant disease. Arguments against prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy center on the need for earlier and more prolonged hormone therapy and the potential increase risk of cardiovascular disease and bone loss (24,25). There is no overall survival benefit of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy in women at average risk for ovarian cancer. In premenopausal women before age 50 years at average risk for ovarian cancer who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, there was a significant increase in mortality from cardiovascular disease compared to women who had ovarian preservation (25). A Markov decision analysis model was used to estimate the best strategy for maximizing a woman’s survival when salpingo-oophorectomy is considered in women at average risk for ovarian cancer who are undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease, and in the women who had salpingo-oophorectomy before age 55 years, there was an 8.58% excess mortality by age 80 (26). Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommend carefully assessing risk, and consideration should be given to conservation of the ovaries in premenopausal women who are at average risk of ovarian cancer (21,22).

Although estrogen therapy is well tolerated and provides good short-term symptomatic relief, recent publications demonstrate that the increased risk of breast cancer in women taking estrogen after hysterectomy makes women reluctant to use it, and long-term compliance with posthysterectomy estrogen therapy is low (27).

In women at risk for ovarian or breast cancer, a formal evaluation with genetic counseling should be offered (see Chapter 37). Salpingo-oophorectomy is associated with a reduced risk of ovarian and breast cancer. Women with a strong family history of ovarian and breast cancer and those who carry germline mutations, BRCA1 or BRCA2 should undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy as their lifetime risk is between 10% and 50% (21,22,28,29).

Based on the finding that many serous carcinomas arise in the fallopian tube rather than in the ovary, it was proposed that bilateral salpingectomy with ovarian conservation should be performed in patients with these high penetrance germline mutations while awaiting more definitive surgical intervention (30,31). One could consider this in women at average risk for these tumors when they undergo hysterectomy for benign disease. It is unknown whether this would substantially decrease the risk of developing these malignancies.

Although salpingo-oophorectomy can be accomplished by laparoscopy or laparotomy in virtually 100% of cases, the success rate for vaginal hysterectomy ranges from 65% to 95% for experienced vaginal surgeons (32,33).

Concurrent Surgical Procedures

Appendectomy

Appendectomy may be performed concurrently with hysterectomy to prevent appendicitis and to remove disease that may be present. The former use is of limited value because the peak incidence of appendicitis is between 20 and 40 years of age, whereas the peak age for hysterectomy is 10 to 20 years later (34). There is no increase in morbidity associated with appendectomy performed at the time of hysterectomy (35). Incidental appendectomies in all abdominal hysterectomies could reduce the morbidity of appendicitis at a later time (35). Appendectomy is performed with vaginal hysterectomy without additional intraoperative or postoperative morbidity (36).

Cholecystectomy

Gallbladder disease is about four times more common in women than men, and its highest incidence occurs between 50 and 70 years of age, when hysterectomy is most often performed. Women may require both procedures. A combined procedure does not appear to result in increased febrile morbidity or length of hospital stay (37).

Abdominoplasty

Abdominoplasty performed at the time of hysterectomy is associated with a shorter hospital stay, a shorter operating time, and a lower intraoperative blood loss than when the two operations are performed separately (38,39). Liposuction can be performed safely at the time of vaginal hysterectomy (40).

Choice of Surgical Access: Vaginal, Abdominal, or Laparoscopic Hysterectomy

From 2000 to 2004, approximately 68% of all hysterectomies were performed abdominally and 32% were performed vaginally. One-third of the vaginal cases were performed with the assistance of the laparoscope (laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy) (1). There are no specific criteria that can be used to determine the route of hysterectomy. The route chosen should be based on the individual patient, but vaginal access is preferred. An alternative access is preferred if there is a narrow pubic arch (less than 90 degrees), and a narrow vagina (narrower than two fingerbreadths, especially at the apex), or if the there is an undescended immobile uterus. The presence of an adnexal mass, cul-de-sac disease, pelvic adhesions, or the assessment of chronic pain may require the addition of laparoscopy for assessment. A previous cesarean section or nulliparity does not contraindicate a vaginal approach (41).

A Cochrane review validated the perception that vaginal hysterectomy is the surgical route of choice for hysterectomy (42). This review included 3,643 patients from 27 randomized trials. It compared abdominal hysterectomy with vaginal hysterectomy and three types of laparoscopic hysterectomies. The main observations were the shorter length of hospital stay, faster postoperative recovery, and decreased febrile morbidity of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy. The report concludes that there are improved outcomes with vaginal hysterectomy, and, when vaginal access is not possible, laparoscopic hysterectomy appears to have advantages over abdominal hysterectomy. Cost-analysis trials demonstrate that laparoscopic hysterectomy can be cost-effective relative to abdominal procedure but not compared with vaginal hysterectomy (43,44). The main cost determinants are the length of hospital stay and the use of disposable surgical devices.

Risk of complication from each type of procedure provides insight into the proper options for the patient. The eVALuate study comprised two parallel randomized multicenter trials, with one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy and the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy for nonmalignant disease (45). Patients with a uterine mass less than 12-week pregnancy were included. The primary end points were assessment of complications. A total of 1,380 patients were recruited. The trial included conversion to laparotomy for the laparoscopic and vaginal groups as a major complication. If you include conversion to laparotomy as a major complication, the number treated relative to those harmed was 20 for the laparoscopic group compared with the abdominal group. If you exclude conversion to laparotomy as a complication, then the complication rates are similar between all groups. All six ureter injuries reported in this series occurred in the laparoscopic group. The overall lower urinary tract complication rate is three times higher with the laparoscopic group compared with vaginal or abdominal procedures. A minor complication, mostly postoperative fever or infection, occurred in approximately 25% of each group.

Perioperative Checklist

It is important to systematically go through a checklist of perioperative measures to effectively reduce potential complications (Table 24.2). If excessive blood loss is expected, intraoperative blood salvage techniques should be considered. All patients undergoing hysterectomy for benign disorders are at moderate risk for venous thromboembolism and require prophylaxis (18). Unfractionated heparin (5,000 U every 12 hours) or low molecular weight heparin (e.g., Enoxaparin, 40 mg) or intermittent pneumatic compression device is recommended. Patients on oral contraceptives up to the time of hysterectomy should be considered for pharmacologic treatment. Mechanical bowel preparation for prevention of infection complications from bowel injury is no longer recommended (46).

Table 24.2 Perioperative Checklist

1. Is the informed consent signed? 2. Is there a recent Pap test documented in the chart? 3. Has pregnancy been ruled out? 4. Are blood products available if needed? 5. Will prophylactic antibiotics be initiated within 1 hour of incision? 6. Was the appropriate antibiotic selected according to American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines? 7. Was the appropriate prophylaxis for venous thromboembolic events chosen? 8. Document that prophylactic antibiotics will be discontinued within 24 hours after surgery. |

Technique

Abdominal Hysterectomy

General Preparation

To reduce the colony count of skin bacteria, the patient is asked to shower. Hair surrounding the incision area may be removed at the time of surgery or before surgery using a depilatory agent. Hair clipping is preferable to shaving because it decreases the incidence of incisional infection, and if shaving is done, it should be performed in the operating room just prior to the surgery (34).

Patient Positioning

For most abdominal cases, the patient is placed in the dorsal supine position for the operation. After the patient is anesthetized adequately, her legs are placed in the stirrups and a pelvic examination is performed to validate the in-office pelvic examination findings. A Foley catheter is placed in the bladder, and the vagina is cleansed with an iodine solution. The patient’s legs are straightened.

Skin Preparation

Several methods for skin cleaning can be recommended, including a 5-minute iodine solution scrub followed by application of iodine solution, iodine solution scrub followed by alcohol with application of an iodine-impregnated occlusive drape, or an iodine-alcohol combination with or without application of an iodine-impregnated occlusive drape.

Surgical Technique

Incision

The choice of incision should be determined by the following considerations:

The skin is opened with a scalpel, and the incision is carried down through the subcutaneous tissue and fascia. With traction applied to the lateral edges of the incision, the fascia is divided. The peritoneum is opened similarly. This technique minimizes the possibility of inadvertent enterotomy, entering the abdominal cavity.

Abdominal Exploration

Cytologic sampling of the peritoneal cavity, if needed, should be performed before abdominal exploration. The upper abdomen and the pelvis are explored systematically. The liver, gallbladder, stomach, kidneys, para-aortic lymph nodes, and large and small bowel should be examined and palpated.

Retractor Choice and Placement

A variety of retractors were designed for pelvic surgery. The Balfour and the O’Connor-O’Sullivan retractors are used most often. The Bookwalter retractor has a variety of adjustable blades that can be helpful, particularly in obese patients.

Elevation of the Uterus

The uterus is elevated by placing broad ligament clamps at each cornu so that it crosses the round ligament. The clamp tip may be placed close to the internal os. This placement provides uterine traction and prevents back bleeding (Fig. 24.1).

Figure 24.1 The uterus is elevated by placement of clamps across the broad ligament. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Round Ligament Ligation or Transection

The uterus is deviated to the patient’s left side, stretching the right round ligament. With the proximal portion held by the broad ligament clamp, the distal portion of the round ligament is ligated with a suture ligature or simply transected with Bovie cautery (Fig. 24.2). The distal portion can be grasped with forceps, and the round ligament is cut to separate the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament. The anterior leaf of the broad ligament is incised with Metzenbaum scissors or electrocautery along the vesicouterine fold, separating the peritoneal reflection of the bladder from the lower uterine segment (Fig. 24.3).

Figure 24.2 The round ligament is transected and the broad ligament is incised and opened. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Figure 24.3 The incision in the anterior broad ligament is extended along the vesicouterine fold. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

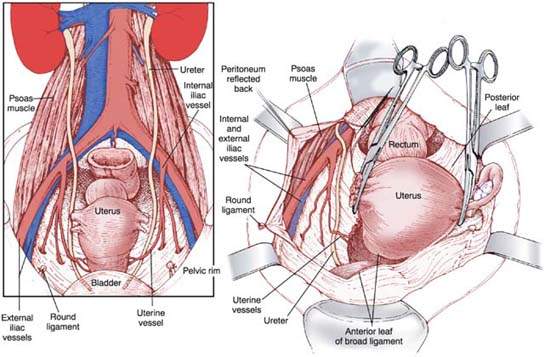

Ureter Identification

The retroperitoneum is entered by extending the incision cephalad on the posterior leaf of the broad ligament. Care must be taken to remain lateral to both the infundibulopelvic ligament and iliac vessels. The external iliac artery courses along the medial aspect of the psoas muscle and is identified by bluntly dissecting the loose alveolar tissue overlying it. By following the artery cephalad to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, the ureter is identified crossing the common iliac artery. The ureter should be left attached to the medial leaf of the broad ligament to protect its blood supply (Fig. 24.4).

Figure 24.4 Identification of the ureter in the retroperitoneal space on the medial leaf of the broad ligament. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Utero-ovarian Vessel and Ovarian Vessel (Infundibulopelvic Ligament) Ligation

If the ovaries are to be preserved, the uterus is retracted toward the pubic symphysis and deviated to one side, placing tension on the contralateral ovarian vessels (the so-called infundibulopelvic ligament), the tube, and the ovary. With the ureter under direct visualization, a window is created in the peritoneum of the posterior leaf of the broad ligament under the utero-ovarian ligament and fallopian tube. The tube and utero-ovarian ligament are clamped on each side with a curved Heaney or Ballantine clamp, cut, and ligated with both a free-tie and a suture ligature. The medial clamp at the uterine cornu should control back bleeding; if it does not, the clamp should be repositioned to do so (Fig. 24.5).

Figure 24.5 Ligation of the utero-ovarian ligament. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

If the ovaries are to be removed, the peritoneal opening is enlarged and extended cephalad to the ovarian vessels (infundibulopelvic ligament) and caudad to the uterine artery. This opening allows proper exposure of the uterine artery, the ovarian vessels, and the ureter. In this manner, the ureter is released from its proximity to the uterine vessels and uterine vessels.

A curved Heaney or Ballantine clamp is placed lateral to the ovary (Fig. 24.6); care is taken to ensure that the entire ovary is included in the surgical specimen. The uterine vessels on each side are doubly ligated and cut (Fig. 24.7). Alternatively, free ties can be passed around the uterine vessels, two cephalad and one caudad, before they are cut.

Figure 24.6 Ligation of the infundibulopelvic ligament. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Figure 24.7 Transection of the infundibulopelvic ligament. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Bladder Mobilization

Using Metzenbaum scissors or Bovie, the bladder is dissected from the lower uterine segment and cervix. An avascular plane, which exists between the lower uterine segment and the bladder, allows for this mobilization. Tonsil clamps may be placed on the bladder edge to provide countertraction and easier dissection (Fig. 24.8).

Figure 24.8 Dissection of the vesicouterine plane to mobilize the bladder. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Uterine Vessel Ligation

The uterus is retracted cephalad and deviated to one side of the pelvis, stretching the lower ligaments. The uterine vasculature is dissected or “skeletonized” from any remaining areolar tissue, and a curved Zeppelin or Heaney clamp is placed perpendicular to the uterine artery at the junction of the cervix and body of the uterus. Care is taken to place the tip of the clamp adjacent to the uterus at this anatomic narrowing. The vessels are cut, and the pedicle is ligated. The same procedure is repeated on the opposite side (Fig. 24.9).

Figure 24.9 Ligation of the uterine blood vessels. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Incision of Posterior Peritoneum

If the rectum is to be mobilized from the posterior cervix, the posterior peritoneum between the uterosacral ligaments just beneath the cervix and rectum may be incised (Fig. 24.10). A relatively avascular tissue plane exists in this area, allowing mobilization of the rectum inferiorly out of the operative field.

Figure 24.10 Incision of the rectouterine peritoneum and mobilization of the rectum from the posterior cervix. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Cardinal Ligament Ligation

The cardinal ligament is divided by placing a straight Zeppelin or Heaney clamp medial to the uterine vessel pedicle for a distance of 2 to 3 cm parallel to the uterus. The ligament is cut, and the pedicle is suture ligated. This step is repeated on each side until the junction of the cervix and vagina is reached (Fig. 24.11).

Figure 24.11 Ligation of the cardinal ligament. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, with permission.)

Removal of the Uterus

The uterus is placed on traction cephalad, and the tip of the cervix is palpated. Curved Heaney clamps are placed bilaterally, incorporating the uterosacral ligament and upper vagina just below the cervix. Care should be taken to avoid foreshortening the vagina. The uterus is then removed with scalpel or curved scissors (Fig. 24.12).

Figure 24.12 Removal of the uterus by transection of the vagina. (From Mann WA, Stovall TG. Gynecologic surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.)